And now… the good news

It’s been a tough year.

[From a talk delivered at UX New Zealand]

A few months ago, my teenage son told me that their class was recently exploring climate change, and it caused anxiety to spike amongst him and his friends. One of his classmates actually stopped coming to school for a few days because of existential angst, and Elliott started to have trouble sleeping.

I’m a designer, so I looked at this as a creative brief. Imagine your kid is having trouble sleeping, what do you do? I know a few things not to do. I know not to deny his feelings: “You’re fine. Toughen up.” But also I know not to despair: “Oh no! I’m a horrible father! I might as well roll over and die.”

No. We’re designers. We’re trained for this! We’re good at taking challenges, accepting them, doing some research, proposing a course of action, and iterating from there. Then we take note of what works and what doesn’t. Then it’s just a matter of doing more of the things that work, and less of the things that don’t. That’s the design process, so it became our guide for approaching insomnia. And here’s what we came up with.

Good news at bedtime.

Here was a grand concept. Right before bed, when his anxiety was high, I’d give him the good news. But you have to be careful with good news. Good news has to be truthful, but also meaningful. For example, if he said “Dad, I’m concerned about the polar bear population,” it’s not helpful to say “yeah, but I I got a screaming deal at the hardware store today.” The good news had to be big, meaningful, and feel like there was a good reason for hope.

So I did some research, and the first day I sat down at his bed to tell him the first good news. “You know how the ozone layer has a hole?” I asked. “Yeah,” he said. “Well, did you know the hole recently closed to its smallest point since 1982?”

“Whoa!” he said. “I know!” I said back. “Now, this is an outlier. The ozone layer gets bigger and smaller throughout the year based on a bunch of factors. So this was just a blip in the data. But actually … the ozone layer is slowly repairing itself. In the 80s we decided that we didn’t want a hole in the ozone layer, so we banned a bunch of things, and the ozone layer is on track to repair itself.”

“Huh,” he said. And day one seemed to have worked pretty well.

On day two, I asked if he knew about polio. He did. “Well,” I said. “Did you know we recently hit zero cases of polio in Africa for three years in a row?”

“Huh,” he said. “I know!” I said back.

Let’s put this in context. Humanhind hardly ever eliminates diseases. It has almost no precedent in human history. We can get the numbers low, but getting to actual zero takes a lot of time, effort, and dedication from lots of people. Getting to zero in Africa is a monumental accomplishment, and we’re well on the way to getting to zero everywhere.

I looked at my son’s face. Day two seemed to be working. He was getting slightly less nervous at night, and he had started looking forward to our nightly global pep talk.

For day three I thought I’d throw him a curveball. I call it Barack Obama’s Time Machine. Barack Obama says if you could be born at any point in all of human history, but you didn’t know what gender or race you’d be … you’d pick now.

This is a very provocative thing to say. But don’t misunderstand. He’s not saying sexism and racism don’t exist. He’s not saying equality has been achieved. He’s not saying we can rest on our laurels or that things will work themselves out organically. Not at all. He’s just saying you don’t want to be a Black person in America 500 years ago, or 200 years or, or even 20 years ago. The same is true for women. The same is true for essentially everyone other than rich white dudes in developed nations. But for them too.

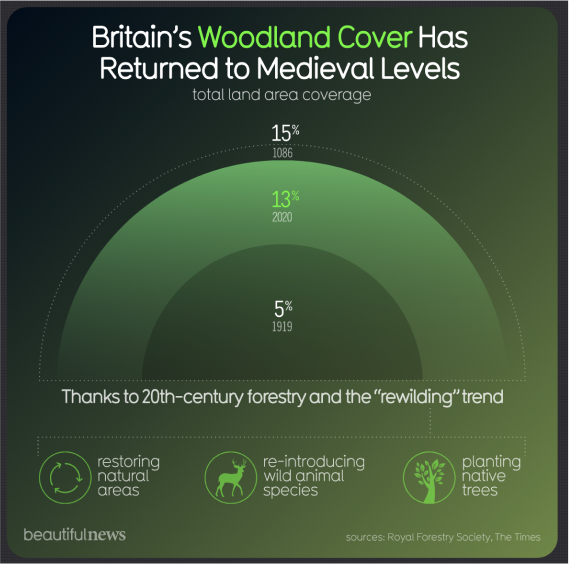

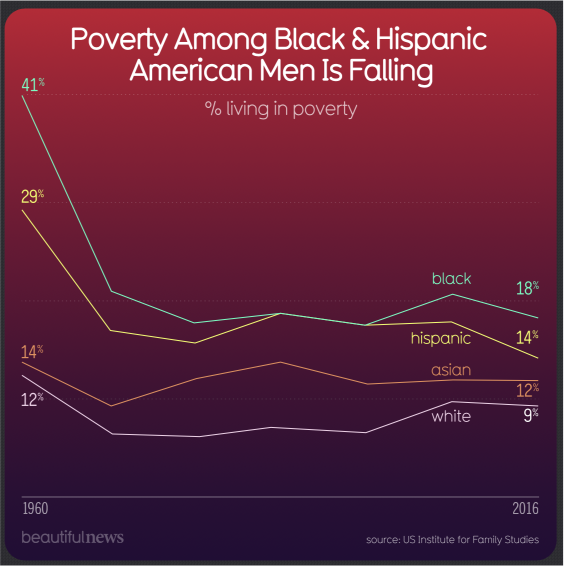

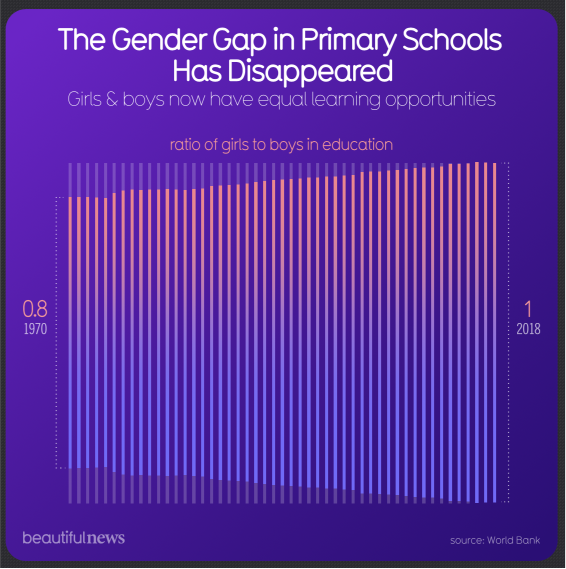

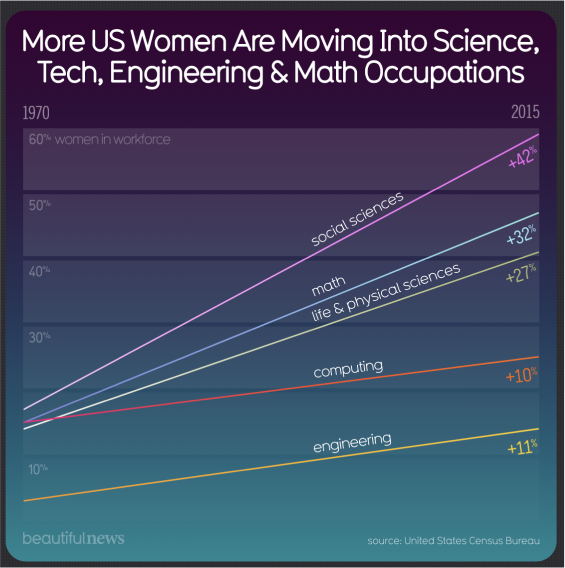

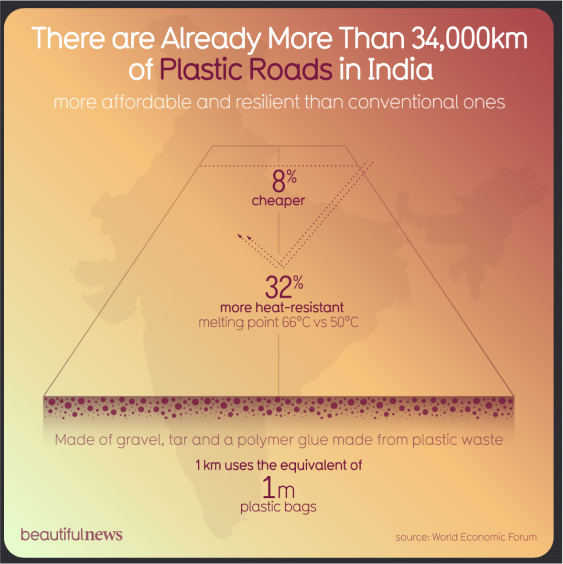

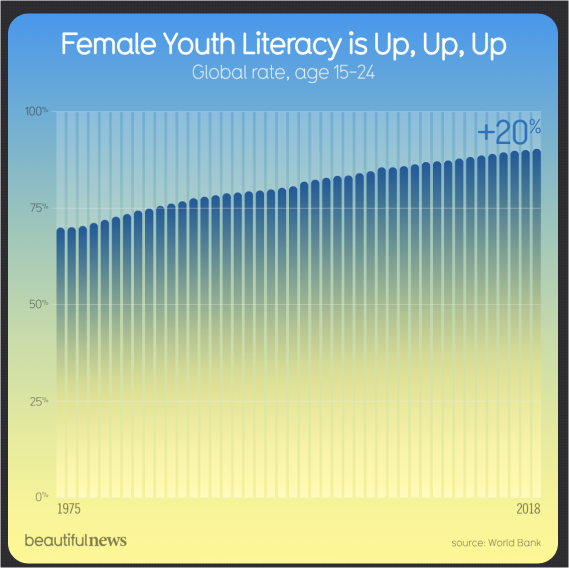

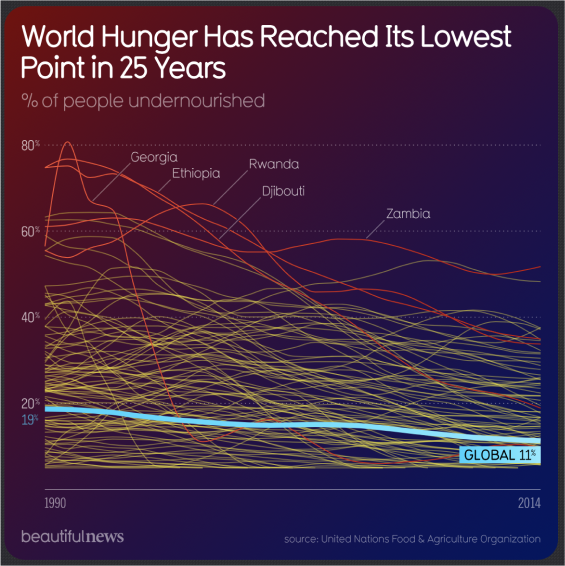

Obama understands things aren’t where we need them to be, but they have been improving. And we have the data to back up these claims. Here’s a big wall of it, thanks to Beautiful News.

The more you look into it, the more you realise that almost any metric you care to look into — war, poverty, sexism, racism, climate change, LGBTQ+ rights, global health — is improving. It’s not that 95% of the world is failing and these stats represent a cherry-picked 5%. It’s the reverse. Almost all metrics are improving, and the things that aren’t are the exception.

So why do we feel so bad?

Now, I’m not here to say the big problems aren’t big problems. I’m not here to say that feeling anxious, or stressed, or disappointed, or tired, or angry aren’t allowed. Of course things seem dire, and in many cases they are. Of course a lot of things are moving far too slowly. And of course, we need to do more.

But I have a theory about why our perspectives are so out of whack from the good news that’s happening across the world and nearly every metric. It’s about denial versus despair.

Imagine the right side of this spectrum is denial. You deny climate change, sexism, and racism even exist. You think it’s all overblown hysteria.

Now imagine the left side of this spectrum — which is where I live, and I bet you do too — is despair. We know climate change is real, and that we’re doomed. You know that racism is deeply rooted into every aspect of our lives, at a systemic level, and we’ve made almost no meaningful progress after all these years. You know that sexism and the patriarchy always has been around, and always will be, and almost nothing has improved.

Well, these two sides of the spectrum disagree on everything, but they do unite on one key detail: they both end up feeling like the effort isn’t going to work.

If one person denies climate change and the other person is so overwhelmed with existential dread that she can’t even get out of bed, they’re both ending up in the same place: paralysis. The same goes for any large topic. And yet there are some people who somehow find a way to muster the will to find a third way that’s not driven by denial or despair.

But these people aren’t centrists, because they’re not accepting half of denial and half of defeat. And don’t call them optimists, just assuming everything is going to be alright. These people are like us: they have a designer mindset.

These are the people that are trained to avoid denial and despair and find a way forward. We follow the same process for all problems, whether climate change, sexism, racism, Covid, disinformation, a kid who can’t sleep, or a button that’s not clickable. We admit the problem is real, research ideas, and then we propose a way forward. Then we do more of the things that work and we try to do fewer things that don’t.

But even if we’ve been trained in this way of thinking, it can be too easy to feel bad and fall into a pit of despair. And the reason why is addressable. The point is best made with an example, so I’d like you to think of a date in your mind. But not just any date. The year you think America will hit peak emissions.

We know the United States of America has been polluting for a very, very long time. It’s the second-largest polluter in the world, and one of the biggest reasons that climate change is such a wicked problem. The states boasts a very strong economy, but not a particularly strong environmental policy compared to a lot of other countries. So it can be hard to convince America to stop polluting so much, despite how important the issue is for the planet.

So I want you to imagine to yourself what year you think America will finally hit peak emissions. What year can America finally start bending the curve downward and make a real dent on carbon emissions? Do you think the estimated year is 2100, or 2070, or 2030, or maybe 2020? Think of the number in your head before scrolling down.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

America hit peak emissions in 2007, 13 years ago. And if this is a surprise to you, it’s one part of the puzzle for why things can feel so out of control and dire. After all, if America can’t even reign in its pollution after all these warning signs, will anything work? If we haven’t made any progress, the system must be broken, the status quo has clearly failed, and so our only option is to throw everything away and start over. Right?

Yet the emissions peak was reached over a decade ago, which changes things. It means whatever decisions were made in the domestic policy, public opinion, industrial subsidies, and dozens of other spaces somehow led to something. And we can analyse what the last 30 years of effort in America to gain some great insights. We can do more of the things that worked, and try to do fewer things that didn’t.

But that’s not all. Do you know when France and the UK hit their peaks?

Yeah. Most countries in Western Europe hit their emissions peaks in the mid-90s, meaning for some people watching this talk, the number of emissions in most countires in the European Union have dropped almost every year that you’ve been alive.

But again, that doesn’t mean we’re done fighting climate change. But it does give us a sense that this is a battle that can be won. After all, it’s much easier to accelerate a trend than have to completely reverse one, and the numbers are actually tilting in our favour.

On that note, what about China? China is much larger than other countries, and they industrialised much later than America and Western Europe. So when are they going to hit their peak?

Disappointing.

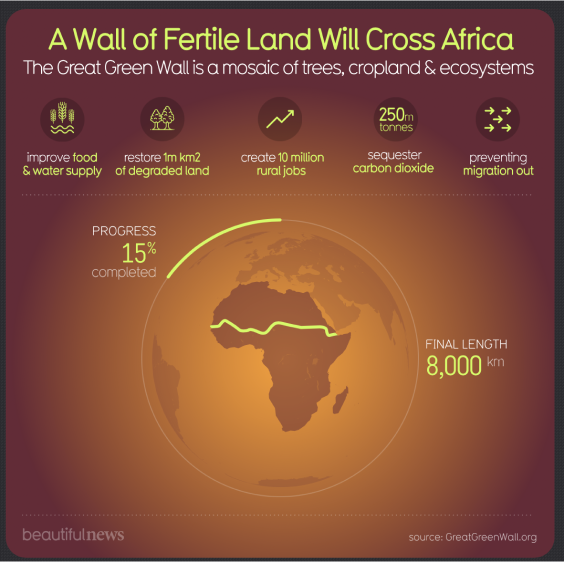

But not so fast. On one hand, it’d be really great if they had hit their peak in 2007 or 1991. But when you look how quickly they’re bending their curve, it’s absolutely staggering. They came to the party late, with a giant population, but if you research what China is doing to reduce and reverse the effects of their emissions, it’s pretty awe-inspiring.

For starters, they’re planting 88 billion trees, but I recommend you research it further. It’s pretty inspiring stuff, and it shows that great things are possible with the right mindset.

(Late breaking change: I went looking to source this claim, and found that China believes it will actually hit their 2030 target 8 years early, in 2022. That’s huge news!)

Here’s another huge number. Some people say this number is so significant that it makes it hard to consider anything else once you learn what it represents.

This number is how many people came out of extreme poverty today. Not in the last year, or decade, but just in the last 24 hours. And the same was true for yesterday, the day before, and every day before that for the last 25 years in a row. In total, over one billion people have been saved from extreme poverty since the year 2000. Nothing like that has ever happened in human history.

And here’s the story behind it. Extreme poverty doesn’t mean you can’t afford the latest iPhone, or things are kind of hard for your family. Extreme poverty is a much bigger deal than most of us can comprehend, and it’s a moral failing of a world far too rich to allow it to happen. Places with extreme poverty are more likely to have wars, lawlessness, atrocities, and sponsor terrorism. It destabilises entire areas, which leads to heartbreaking stories of generations trapped in a struggle for survival.

So in 2000, the world decided that having two billion people in extreme poverty wasn’t acceptable anymore. So they set a target of cutting the rate in half by 2015. Not only did the UN and supporting countries reach their target, they reached the target five years early. This is one of the greatest accomplishments in all of human history, and it happened ahead of schedule, but you probably haven’t heard about it. And the reason why is understandable. We expect news to be an outlier, so we’re not accustomed to long-term good news story arcs. Meaning it doesn’t end up in our media diets.

A news story that runs once a day that says “Today another 137,000 people were saved from extreme poverty, which leads to increased rates of education, which leads to longer life expectancy, healthier communities, less war, and more empowered citizens, especially women,” you’d tune it out eventually. It’s not considered real news, even though it’s more meaningful than most other things you’re reading. By far.

And here’s another encouraging tidbit: areas that get out of extreme poverty stop polluting as much. No one wants to use dirty coal stoves with poor ventilation in their homes, but if it’s all you can afford, it’s all you have. Giving these people real jobs for real wages means they invest in greener technologies, which has a huge ripple effect across all of humankind.

So the UN set a new goal to get to zero people in extreme poverty by 2030. Zero. Like polio.

We’re currently down to about 700 million people, but I’ve got some bad news. Most estimates say that getting to zero probably won’t happen by 2030. So when faced with this information, what did the lawmakers, NGOs, and people on the ground do? Deny it, and not change the plan? Get paralysed with despair? Of course not. That would mean doing nothing.

No, they’re in the designer’s mindset. They’re admitting that they’re not going to hit their number, analysing the data to see what sorts of things worked, recommitting to doing more things that work, and fewer things that don’t.

If you’re inspired by this, the way I was, there are some great books you can read to learn more. Here are some I’d recommend.

Enlightenment Now is the inspiration for this talk, and it’s Bill Gates’ favourite book of all time. For good reason! This guy writes about 25 chapters about giant societal issues: sexism, racism, climate change, war, terrorism, public health, and so on, and he explains what’s being done. He explains where the progress is. And his thesis is not “everything is fine, let’s stop working so hard.” It’s “we know what things work. Let’s do more!”

The Fate of Food is similarly pragmatic and clear-eyed. It’s saying “We know the world is getting warmer, and a lot of crops are going to die unless we do something. So here are the scientists, farmers, organisations, and governments who are charting a way forward.” Not denial, not despair, just good old fashioned invention, imagination, iteration, and hard work.

Finally, The Breakthrough is a similar book about the multi-decade struggle to find a cure for cancer. It’s absolutely staggering what scientists and doctors have been discovering, and this book is why I wasn’t surprised when we completely shattered the expectations with not one, but two Covid vaccines with unheard of levels of effectiveness.

Remember, it was only a few months ago where we were being warned that we might never have a vaccine at all. These sorts of incredible breakthroughs are almost feeling commonplace. But historically, they absolutely are not. We are living in a golden age, even if it doesn’t feel like it yet.

One of the easiest ways to feel better about the progress we’re making as a world is to dedicate yourself to it. Climatescape is a great website to show all the amazing companies springing up to fight climate change, and you can go to Climatebase to find a job in this space. I interviewed with two climate change companies and I was walking on air for a week afterwards because their technologies and approaches were so inspiring and exciting.

If you’re a designer or work on building products, your skills have never been more in demand, and that demand will only increase in the future. The designer mindset means avoiding denial and despair in favour of proposing approaches, then iterating based on data. It’s what we were trained to do, and it’s our greatest benefit to humanity. It’s our calling.

And it’s not just us, of course. When you dig into the data and see all the things that are getting better, the designer mindset is everywhere. Politicians, entrepreneurs, CEOs, scientists, teachers, activists, artists, everyone. We’re designed to see problems, come up with better ideas, try them out, and iterate off what we see. It’s not just a designer thing, it’s a human thing.

This is why, as controversial as it sounds, I know we can do it. Whether “it” is your own mental health or insomnia, a dynamic in your family or team at work, or even your broader community or country. We can do it, and the reason I know that is I’ve done the research. And it’s clear.

We can do big, impossible, unprecedented things. Because we always have.

Videos that inspired this talk

- When writing and performing this presentation, I was aiming to make people feel the way Cabel made me feel back in 2013 with his talk at XOXO. I even designed my slides as a direct homage to his to make the inspiration clear. An all-time classic.

- The world feels a lot less overwhelming and scary when my friend William Van Hecke explains it. He has a talk called Your App Is Good and You Should Feel Good, and I highly recommend it to anyone building anything.