Design by crisis: tectonic shifts in design constraints

How sudden shifts in design constraints can blur possible long term effects of design choices and why designers (and everyone else) should care.

Co-authored with Derek A. Kuipers

A few days after the 9–11 terrorist attacks back in 2001, a US cable news network aired a clip of an interview with an inventor who had come up with a solution for getting trapped in a burning skyscraper: a cheap, readily available, easy-to-use parachute system that had to be strapped on one’s back in case of such an emergency. Suddenly, the interview turned into a slapstick scene: while demonstrating the prototype, the inventor got tangled up in his own invention, disproving the easy-to-use part and providing some welcome comic relief.

A few days after the 9–11 terrorist attacks back in 2001, a US cable news network aired a clip of an interview with an inventor who had come up with a solution for getting trapped in a burning skyscraper: a cheap, readily available, easy-to-use parachute system that had to be strapped on one’s back in case of such an emergency. Suddenly, the interview turned into a slapstick scene: while demonstrating the prototype, the inventor got tangled up in his own invention, disproving the easy-to-use part and providing some welcome comic relief.

Although well-intended, the idea was far-fetched too: offering parachutes as safety devices in case of an emergency in a high-rise building merely changes certainty of death into a high probability. Using a parachute properly takes substantial training, using a parachute to jump from a building, even more. The chance that a novice, inexperienced user of such a device would survive the plunge would be slim at best. The questionable feasibility aside though, it is perfectly understandable that these initiatives emerge. Emergencies and crises cause immediate problems and designers and engineers are trained to solve problems, so they are likely to react in that way.

Now, once again, we have a crisis at bay: a deadly pandemic that disrupts societies on a global scale. We are confronted with immediate problems: a shortage of medical supplies, overwhelmed health professionals, or the inability to properly track the spread of a deadly virus. And once again, designers and engineers rise to the cause: they start proposing and producing solutions at lightning speed, with enthusiasm and pragmatism. Anything to help.

That was what our parachute inventor probably had in mind, too. But in hindsight, It would probably have been a better idea to thoroughly assess all the escape routes in buildings such as the former WTC and try to make them better, safer and more resilient. It would have been better to make high-rise buildings more fire-proof (as the Grenfell tower fire in 2017 sadly proved once again). It would have been better to think of ways that would hinder hijackers to take control of a plane and plunge it into a building. It would be even better to start thinking about why people are willing to hijack an airliner and plunge it into a building.

To put it short: The quick elimination of the most obvious symptom of a problem mostly does not contribute to the best solution. On the contrary: it will likely cause new, maybe even worse problems. Especially when designing for health, it is important to try and understand the dynamics and constraints at stake, because there can be lessons learnt from this crisis.

Crisis driven design

Victor Papanek states that all men are designers and design is what makes us human: “The planning and patterning of any act towards a desirable foreseeable act is what constitutes a design process” (Papanek 1972). Plessner’s concept of eccentric positionality states: As humans, we are aware of what we are and in turn we are aware of that (Plessner 1975). We are aware of contingency, our vulnerability, our imperfectness and we need, design, create and use technology in an effort to ‘solve’ that imperfectness.

Whenever an acute, catastrophic, traumatic event occurs, this sense of imperfectness ends up in the spotlight and causes an irresistible drive to design and make. Both out of enthusiasm, honest pragmatism, a sincere will to help, often heart-warming design-initiatives arise. We are all witnesses to wonderful expressions of participative citizenship, resourceful entrepreneurs and really good examples of how to deal with a totally changed society, with changed needs and shortages.

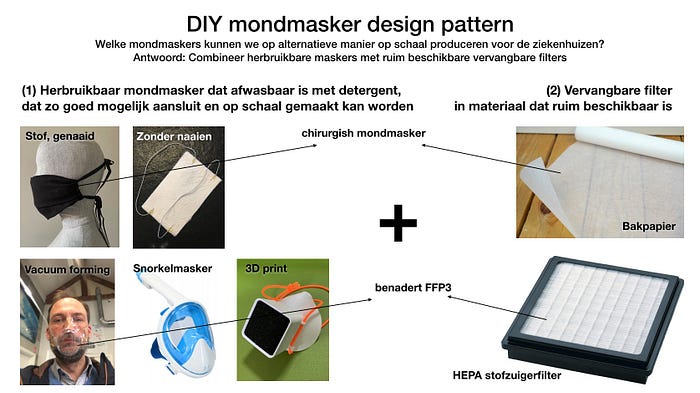

For example, when the full scale of the SARS-Cov2-pandemic became apparent, there were clear signs of an imminent shortage in medical grade face masks. Designers around the world rose to the occasion, sourced and proposed open design patterns to enable anyone with a sewing machine to start fabricating face masks. In the trail of the first face mask patterns, 3d-printed frames for face shields emerged as well. Complete funding actions were started and now, the frames are printed by the 1000’s.

Also, as patients with a severe case of COVID-19 eventually may develop a double pneumonia, the need of ICU-units, and ventilators in particular, would rise exponentially and shortages were projected to be imminent. This problem was tackled soon enough: Fab labs, universities and even Formula 1 teams started up their 3D printers and laser cutters, ad-hoc hackathons were initiated and the first results were shared around the internet. Be it lo-fi, or hi-fi, everyone with some engineering skill and a good sense of prototyping chipped in.

And then there were the smartphone apps and cell phone tracking services. The capabilities of smartphones to track location of individuals and location of others nearby were recognised as potential data sources to track and possibly curb the spread of the virus. Apps to survey symptoms, apps to check location of possible infected patients and apps that control location data of individual citizens to enforce lockdowns in certain areas or even countries. Some of these apps are state-sponsored, others were intended for scientific research; even others were initiated by tech companies.

The common denominators in these design processes seem to be necessity, enthusiasm, pragmatism, and available technology. Apart from core functionality, most other design requirements and constraints seem to have given way to speed of production and availability. This apparent shift in priorities is important to notice.

Prototyping is not improvising

When designing and producing products for health, there are regulations and constraints to take into account: durability, serviceability, sterile production environments and ergonomics to name a few. These regulations (classifiable in constraints) are in place for good reasons. You do not want medical supplies to create a false sense of safety. You do not want these supplies to become the carrier of diseases themselves, nor do you want these products to suddenly break down at the moment someone’s life may depend on it.

There are already examples of unintended, dangerous behavioural effects due to the use of improvised health devices. The most obvious example are the homemade mouth caps. Non-compliant mouth masks give a false sense of protection: precisely because of these mouth masks, people thought they were protected and no longer complied with the prescribed safety measures, such as social distancing. These types of behavioural effects often come to light during planned testing to consciously explore the multi-stable use of artifacts.(Albrechtslund 2007; Ihde et al. 2008) If a relatively simple artifact such as a mouth mask already has far-reaching behavioral effects, what about the unexplored consequences of open-source respirators, virus tracking apps or changes in laws?

This is why it may become problematic when we allow these crowd-sourced products to find their way into hospitals, for example. All the hard work, good intentions and positive energy aside.

The drive to design a way out of the immediate problems the SARS-Cov2-pandemic creates, seems to trigger a tendency towards sidestepping important regulations in order to speed up the process. It is no longer clear whether designers are prototyping towards a minimal viable product or merely improvising within a certain time frame and availability of tools and materials. Most outcomes can be called prototypical at best, and would require several iterations of thorough testing and refining before being released into a clinical setting and made ready for production. Concrete implementation of testing and production strategies remain unclear with most proposals. For example; results from so-called hackathons -once started as computer programming competitions- seldom translate into practice for a reason.

Designing means dealing with constraints

To come to a better understanding of the dynamics of this phenomenon, we need to observe the very act of design itself. “A designer solves problems within a set of constraints” (Monteiro 2012). Without well defined and respected constraints, a design process is doomed to spiral out of control, miss the proper objectives and will mostly result in useless, sometimes even harmful artefacts. Design constraints can be practical or technical: they can describe a certain budget, production specifications, the type of supported hardware, or the required lifespan. Design constraints can also consist of more goal oriented specifications: the type of end user (Cooper et al. 2014), environmental regulations or ethical design principles (Monteiro 2019).

Even the most simple design processes involve handling multiple constraints on multiple levels. This means that in general, design processes are challenging, often wicked.

Even under pressure, wickedness remains upright

A well-known explanation of why design processes are challenging comes from research into the design of information systems (Hevner et al. 2004). However, it is not far-fetched to consider these aspects as useful in thinking about the design of, for example, health artefacts required in times of need. From the literature, wicked problems are characterized by unstable requirements and constraints based upon ill-defined environmental contexts, and it is precisely in times of crisis that these aspects remain vigorously upheld. In fact, due to a lack of time, money, resources and limited possibilities to collaborate, one could say that the act of designing has become even more wicked. In the context of this article, it is particularly significant that designing suffers from complex interactions among subcomponents of problem and resulting subcomponents of solution. Or as expressed by Lawson: ‘Design problems are often both multi-dimensional and highly interactive. Very rarely does any part of a designed thing serve only one purpose’ (Lawson 2006). This last characteristic requires special attention because it contains a warning.

A fifth generator?

It is a sophisticated process of balancing internal and external design constraints, which ultimately determines the appropriateness of a solution. This process takes time, creativity, inventiveness and experience. Even before a solution can be thought of at all, this process of appropriating determines the contours and nature of the design issue. Especially in times of crisis it is this delicate process that comes under serious pressure, and even more often is simply skipped. Lawson appointed four generators of design constraints, namely the designer himself, the client, the end user and finally the legislator.(fig. 1)

Society and the design community react in a way as if with the advent of SARS-Cov2-pandemic a fifth generator is in place, one that breaks open existing constraints, makes them less important or even overrides them. And sure, this crisis is an absolute, external force to be reckoned with. It disrupts and overrides the sophisticated mechanism of checks and balances between the four generators that normally exists in a well executed design research project. Even in periods of peace and quiet, external constraints are factors that need to be taken into consideration. They are extremely important. They have a high degree of influence on the design choices to be made and on the final form and content of the artefact to be designed. In normal circumstances there is time to explore and map these external constraints. New or inexperienced designers have the time to learn from wrong assumptions, poorly understood challenges or unexpected outcomes. How different is this in times of crisis: this space is not available and the consequences may be disastrous.

What it takes to solve truly wicked problems

What we see in most lo-fi proposals is that they merely aim at solving the problem of shortage, and to do that, rigid design constraints, especially in terms of legislation and guidelines, are loosened or simply left out of the equation. Instead of thoroughly working towards a solution, these designs are more focused on eliminating the problem.

However, we can see from the more high-end engineering initiatives that it is possible to still design within important constraints such as serviceability, durability and hygiene, while keeping the proces at speed. The ventilator proposals from Mercedes AMG and Delft University for instance, do. The latter, an initiative from students that worked round the clock for days, has been thoroughly tested at Hospital ICU’s and looks promising in case of shortages. Even so, the question remains how many can be produced at what time span. But the point here is: designing health artefacts under the pressure of time is a wicked problem and it takes a good amount of experience and expertise, and a multidisciplinary approach. (Kuipers et al., n.d.).

The same can be said of the ongoing discussion on track-and-contact-apps, that right this moment have gained a foothold in the way the Dutch government aims to address the future ‘sensible lift’ of the current ‘intelligent lockdown’. There are countless apps and technologies that offer tracking, tracing and contact-verifying, which may look promising when it comes to mitigating new infections. But again, this product needs to be made by people that are well-informed in both technology, privacy and public health care, preferably epidemiology. A multi-disciplinary and non-political team, working from the very area the artefact actually will be deployed, will possibly conceive the best proposals.

Cross (2004) states that the lower levels of design expertise are often inclined to be more problem-focused, exactly what we’re seeing right now. A lot of shortcuts to a quick fix for a pressing problem. On the other hand, the more experienced designers work in a solution oriented way. Both are in the process of designing, both give all they have, but the more experienced designers are used to exploring the constraints and involve them in their process. But don’t be fooled: a pandemic is not the fifth generator, it should just make us value the constraints in place even more. It’s not a licence to improvise with people’s lives.

To end on a positive note: the authors see all kinds of wonderful initiatives happening around them. Especially in the field of social engineering, organizing togetherness, addressing loneliness and facilitating well-being, the ingenuity and design spirit is great. The issue we wanted to address is that designing is not suddenly risk-free or straightforward.

Stay safe, everyone.

Sources used:

Albrechtslund, Anders. 2007. “Ethics and Technology Design.” Ethics and Information Technology 9 (1): 63–72.

Cooper, Alan, Robert Reimann, David Cronin, and Christopher Noessel. 2014. About Face: The Essentials of Interaction Design. John Wiley & Sons.

Cross, Nigel. 2004. “Expertise in Design: An Overview.” Design Studies. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2004.06.002.

Hevner, Hevner, March, Park, and Ram. 2004. “Design Science in Information Systems Research.” MIS Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148625.

Ihde, Don, Pieter E. Vermaas, Peter Kroes, Andrew Light, and Steven A. Moore. 2008. “Philosophy and Design: From Engineering to Architecture.”

Kuipers, D., G. Terlouw, B. Wartena, and R. van Dongelen. n.d. “Design for Vital Regions in Vital Regions.” In Vital Regions, SAMEN BUNDELEN VAN PRAKTIJKGERICHT ONDERZOEK, edited by Marc Coenders, Janneke Metselaar, and Johan Thijssen, 251–61. Eburon.

Lawson, Bryan. 2006. How Designers Think. Routledge.

Monteiro, M. 2019. Ruined by Design: How Designers Destroyed the World, and What We Can Do to Fix It. Mule Design.

Monteiro, Mike. 2012. Design Is a Job. A Book Apart.

Papanek, Victor. 1972. Design for the Real World.

Plessner, Helmuth. 1975. “Die Stufen Des Organischen Und Der Mensch.” https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110845341.