Designing for change: understanding behaviour change theory

By exploring 3 key Behaviour Change Theories, we look at how they inform app design and the extent to which apps can really change behaviour.

If changing behaviour were simple, we’d all be perfect, and household names like Cadbury and Haribo might struggle to survive.

Yet, altering behaviour is a complex challenge.

The digital marketplace is saturated with apps promising significant behaviour change, targeting various aspects of personal development from weight loss and meditation to quitting smoking and improving financial habits. Among these, I have contributed to developing Kitche, an app designed to change food waste behaviour. However, many of these apps fail to enact lasting change and from firsthand experience, I understand the complexities and challenges involved in designing an app that truly achieves its intended outcomes.

While UX designers are quick to refer to ‘guiding UX principles’ based on cognitive biases, there are many more insights from psychology that can inform our design thinking and approach. As a behavioural psychologist who has studied many different theories of behaviour change (A literature review found 82 different theories of behaviour change) I wanted to share 3 of the most prominent theories, break them down and explore how they can help us design more effective behaviour change apps.

Furthermore, I explore the pervasive influence of social media apps, which, despite not explicitly targeting ‘behaviour change’ have subtly embedded themselves into our daily routines. Why is it so challenging for us to intervene effectively when some products seem to do it effortlessly?

What is Behaviour Change?

Behaviour change is about altering habits and behaviour for the long term. ‘Long term’ is key here, the change needs to be habitual and sustained, not a one time event. The duration required for it to be considered behaviour change is not defined and largely depends on the action itself; for instance, altering one’s diet occasionally may not be as impactful as choosing train over air travel only a few times.

A lot of behaviour change research and theories focus on conscious behaviour change in relation to health behaviour such as quitting smoking, eating healthy and environmental behaviour such as recycling more and wasting less. Likewise, behaviour change apps are frequently developed to specifically address these types of behaviours. For the purpose of my exploration I am going to look at the Theory of Planned Behaviour, The Transtheoretical Model and Self Determination theory, each providing unique and valuable insights into design

Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

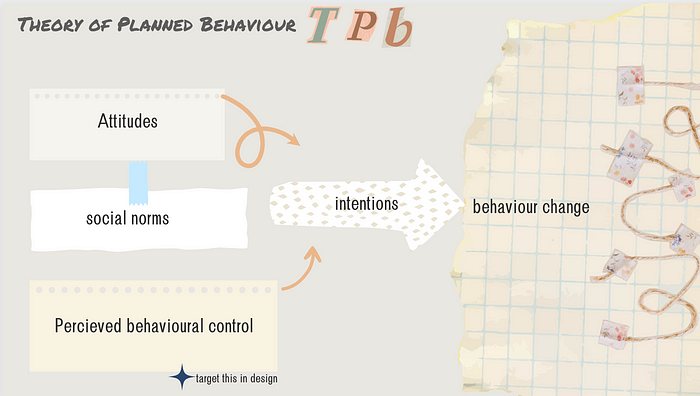

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) is used by behavioural psychologists to explain intentional changes in behaviour. Based on the Theory of Reasoned Action, It suggests that intentions mediate the relationship between one’s attitudes and actual behavioural change, influenced by additional factors such as social norms (what other people think of you) and perceived behavioural control (how hard you think the behaviour change is).

Let’s use smoking as an example: If you hold a negative attitude towards smoking and face social pressures to quit (social norms), you are likely to form an intention to stop. If you also perceive quitting smoking as manageable (perceived behavioural control), TPB suggests you will likely succeed. Conversely, if your friends think smoking is cool (social norm) and you think quitting will be hard (perceived behaviour control), your intention to quit may be weak or non-existent, and you’ll likely continue smoking.

How can The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) improve behaviour change app design?

The theory suggests we should focus our attention on three influential factors: attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioural control.

- Improving attitudes with education, positive feedback and gamification: Attitudes can be influenced through various methods such as cognitive dissonance and conditioning. Cognitive dissonance occurs when there are conflicting beliefs leading to an attitude shift, so incorporating resources and information that challenge existing beliefs can positively affect attitudes. Similarly, positive reinforcement and gamification can also modify users’ attitudes through conditioning.

- Influencing Social Norms with community features: Integrate social features such as sharing achievements, collective challenges and a community. This will help shift users’ perceptions of what others think and instil a sense of belonging, normalising new intentions and behaviours.

- Improving Perceived Behavioural Control with achievable goals: Perceived behaviour control refers to how difficult a user perceives a task to be. By making tasks feel easier by setting short-term achievable goals and providing tools to support them, we are able to boost user confidence and self-efficacy.

The Theory of Planned Behaviour is valuable for its simplicity and comprehensive approach, incorporating both personal attitudes and social elements, internal and external influences. However it fails to capture the ‘long term’ aspect of behaviour change — its linear approach misaligns with cyclical patterns observed in real-world behaviour.

The theory also focuses on aspects such as social norms and attitudes that are deeply ingrained in our value systems and lives, and it may be overly optimistic to assume that an app can significantly influence such factors. Nonetheless, the component of perceived behavioural control within TPB provides a valuable focal point for app design, often acting as a significant barrier in health-related behaviour changes.

Key Takeaway from TPB for Designers:

- Attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioural control shape intentions and ultimately drive behaviour change

- Gamification, positive feedback and education can have a positive influence on attitudes

- Community features can improve social norms and pressures.

- Achievable goals and support can impact someone’s perceived behavioural control, a critical focus area for designers

- TPB fails to capture the temporal aspect of behaviour change.

The Transtheoretical Model (TTM)

The Transtheoretical Model (TTM) addresses what the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) overlooks — that behaviour change is not a singular event but a multi-stage process. Instead of concentrating on the influences and causes, TTM focuses on mapping out the stages of change, providing more insight into the “what” of behaviour change rather than the “why.”

TTM suggests that behaviour change progresses through six cyclical stages, and individuals can move back and forth between these stages: Pre-contemplation, Contemplation, Preparation, Action, Maintenance, and Termination/Relapse. Let’s explain them in relation to quitting smoking.

- Pre-contemplation: Smoker has not considered quitting, still puffing away.

- Contemplation: Smoker begins to acknowledge that they could quit.

- Preparation: Smoker plans and prepares to take action (gets a vape and a nicotine patch).

- Action: Active steps are taken to quit, cigarettes are binned.

- Maintenance: Sustained effort is made to not relapse.

- Termination/Relapse: Smoker is no longer a smoker — or they relapse and cycle restarts.

The model recognises that change does not occur overnight or just in an ‘Action’ phase, which is the time when the most recognition and positive feedback is received from others. It highlights that significant behaviour change is gradual and requires more engagement than just downloading an app. Naturally humans do not like slow processes and delayed gratification. In fact, we can act irrationally to avoid it and this is one of the biggest changes to behaviour change interventions.

What does The Transtheoretical Model (TTM) teach us about designing behaviour change apps?

- Marketing as part of behaviour change: Contrary to some product designers’ beliefs, marketing is not just about getting people to buy in but is integral to behaviour change itself. Raising awareness can initiate pre-contemplation and influence the decision to engage with a product contributing to long term change.

- Effective Onboarding and instant feedback: Creating a welcoming, user-friendly interface with clear, achievable goals can improve user commitment from the outset. Do not delay positive gratification — give users wins from the beginning or they might not hang around.

- Support Through Action: Apps must excel during the action phase by providing robust support. Features like positive reinforcement, progress tracking and essential resources are critical to facilitate the behaviour change process. (Much like PBT suggests).

- Focus on Retention: Maintaining user engagement through the maintenance stage is crucial. Apps should deliver fresh content, continuous reminders and rewards for ongoing behaviour to ensure users remain committed.

The Transtheoretical Model underscores how important retention is for behaviour change. If users do not return, the maintenance phase is not reached, and the action becomes another fleeting attempt at change. The model also highlights how an intention needs to be present before downloading the app. Initial phases — Pre-contemplation, Contemplation, and Preparation — rely on real-life motivations and individual circumstances, although effective marketing might contribute.

What the TTM also considers is users may relapse. While designers are fixated on new users, we also need to remember we have dormant users too! They are not just as important but actually an easy target for behaviour change.

Key Takeaway for Designers:

- Behaviour change has various phases and you can move between them over time.

- Marketing can contribute to pre-contemplation and contemplation stages in behaviour change products

- Effective onboarding and instant gratification is key

- Retention is really important for maintaining change

- Don’t forget to design for dormant users too!

Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

While some psychologists may classify Self-Determination Theory (SDT) primarily as a motivational or wellness theory, commonly discussed within the context of positive psychology, I think it is hugely important when it comes to understanding behaviour change. SDT suggests that by satisfying three basic psychological needs — autonomy (freedom to choose), competence (being capable) and relatedness (feeling connected to others) — we become intrinsically motivated (inherently driven to do something).

When we are intrinsically motivated our behaviours are driven by personal satisfaction and enjoyment rather than external pressures. For example, if you have a passion for mathematics and enjoy doing homework, you’re far more likely to excel than if you’re merely trying to please your father.

The theory suggests that intrinsic motivation is essential for driving long-term behaviour changes because these behaviours are self-sustaining and inherently rewarding. It also differentiates between various types of motivation regulation. I’ll go back to the smoking example to explain their differences.

- External Regulation: Actions are performed to satisfy an external demand e.g. a person might try to quit smoking to avoid a fine.

- Introjected Regulation: This involves taking external motivations and internalising them, but not fully. For example, someone might attempt to quit smoking to feel better about themselves and avoid self-imposed guilt.

- Identified Regulation: This is more autonomous and involves personal recognition of the importance of a behaviour and accepting it as one’s own. A smoker might decide to quit because they recognise it’s important for their health.

- Integrated Regulation: This occurs when motivations are fully assimilated with one’s values and needs. For example, quitting smoking because it aligns with one’s value of living a long, healthy life to be there for family and loved ones. With this comes genuine positive feelings when not smoking.

This theory is really valuable as it distinguishes between externally influenced behaviour changes, which are susceptible, and self-sustaining behaviour changes that are resistant to external influences.

What does Self-Determination Theory (SDT) theory teach us about designing behaviour change apps?

- Fostering Relatedness: Creating a sense of community within the app can significantly boost engagement and commitment to the desired changes. Making someone feel part of something is important for motivation.

- Make users feel competent through achievable goals: It is crucial that the app provides tasks that users can successfully complete. These tasks should come with positive feedback to reinforce users’ capabilities, and challenges should be well-calibrated to their skill level to prevent frustration. Make the user feel like the master!

- Promoting Autonomy through personalisation: Allow users to make choices about the process — such as selecting a ‘day off’ from exercise routines or choosing the type of exercise they prefer —. Even smaller choices, like selecting an avatar, can have an impact. This is will help assimilate the task with user’s values and integrate regulation.

- Making Apps Enjoyable: Design apps to be fun and engaging, rather than feeling punitive or overly directive. This ties in with the concept of flow, a state when someone is fully absorbed in a task because they enjoy it and they are oblivious to external distractions.

- Be careful of the tone: Making an app authoritative and overly pestering can put a user off and negatively influence behaviour change.

While Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is typically viewed as a motivation theory, its importance in understanding behaviour change cannot be overstated. This theory highlights the individuality of behaviour change as autonomy, relatedness, and competence are constructs that differ from person to person as they are shaped by individual values. This shows how a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach in design is ineffective as it cannot align with everyone. Fortunately with the advent of AI and clever algorithms, the potential for creating sophisticated and personalised app experiences is now possible.

Key Takeaway for Designers:

- To create self-sustaining behaviour change basic needs need to be met: Autonomy, Relatedness and Competence

- Give users achievable goals so they feel competent

- Community in apps can help users with feelings of relatedness

- Give the user choice and personalised experiences so they can feel autonomous and align with their needs and values

- Make apps enjoyable!

- Do not be too authoritative in tone and design

So, what does all this mean? I’ve presented you with a range of theories — and yes, there are many more out there attempting to understand and model behaviour change. It’s clear that certain recommendations recur across multiple theories: Both TPD and SDT highlight the critical role of community in effective behaviour change. Common elements such as positive feedback, gamification to condition users towards a behaviour and realistic, incremental goal-setting also emerge as crucial strategies for enhancing perceived behavioural control and instilling competency in users.

However, many of these strategies are already well-integrated into design and behaviour change apps. For instance, in Kitche, we implemented features such as rewards for users who reduced waste, personalised goals, and weekly waste tracking. We even introduced a community section to connect users locally around the goal of reducing food waste. Despite these efforts, achieving measurable behaviour change remained challenging.

I believe two key areas are both disproportionately important and challenging to implement: intrinsic motivation and maintenance/retention. The former, intrinsic motivation, is rooted in personal values and enjoyment, which are typically stable across a lifetime. We might be able to shift attitudes but value systems are resistant to change, thus, it is nearly impossible for an app to alter these directly. Instead an app must align with an individual’s existing values. However, this means that either it needs to be highly sophisticated in its personalisation or only target a subset of people who do align e.g. a food waste behaviour change app like Kitche will only target environmentally conscious people.

The latter, retention, stands as the major hurdle for apps. Health and fitness apps, for instance, have an average 30-day retention rate of only 2.8%. This raises a critical question: Are apps even the right tool for behaviour change, or are we wasting our time designing them?

However, it’s clear that some apps have profoundly shifted behaviours, with whole generations now seemingly glued to their phones. Social media apps, for instance, boast retention rates significantly above 70% at 30 days. So, how have these apps become so seamlessly integrated and deeply embedded into our lives, altering the way we sleep, eat, and socialise?

There are several reasons why social media apps are so pervasive compared to behaviour change apps:

- Instant Gratification: Users receive immediate rewards, such as likes and comments, which continuously engage their attention.

- Lower Psychological Investment: Engaging with these apps requires minimal effort or emotional investment — especially compared to behaviour change apps, making them easy to use frequently.

- Personalisation and Algorithms: Content is tailored to individual preferences, enhancing relevance and stickiness and intrinsic motivation.

- Social Connectivity: These apps strengthen social bonds by connecting users with friends and communities. (Relatedness and Social norms).

- Ease of Use (“the scrolls”): The simple, addictive design of endless scrolling significantly lowers barriers to prolonged use and retention.

I believe the final point about the simplicity of design is crucial. While integrating insights from various behaviour change theories — such as the importance of positive feedback, community building, and achievable goals — we must be careful not to overcomplicate the experience. It might be the complexity of apps is currently acting as a barrier to change. Indeed, the success of social media platforms, with their infinite scroll and instant gratification, shows how simple yet powerful design elements have captivated users.

While it’s vital to draw from psychological theories to inform our designs, we must also make these changes subtle and unobtrusive, seamlessly integrating into users’ lives without overwhelming them. By marrying theoretical depth with practical simplicity, we could hopefully start to design more successful behaviour change apps.

Further reading:

Behaviour Change and digital behaviour change interventions: A noobs guide by Nipuna Cooray

Behaviour Change Techniques in UX/UI Design — Panacea Digital by Marta Denkiewicz

Article Written by Letitia Rohaise (letitiarohaise.co.uk). Product Designer with a Masters’ in Psychology. Letitia is an advocate for integrating cultural psychology into design, ensuring products are meaningful and accessible across diverse cultural contexts.