Embracing the absurd in your design practices

Rediscovering authenticity and unconventional thinking in a world obsessed with sameness and scalability.

If you have done any product work in the last decade or two, you have inevitably heard of the Design Thinking ideology. Hell, you might have become a design-thinking zealot and championed it in your teams.

It makes sense if so. By all accounts, it’s a great user-centric ideology.

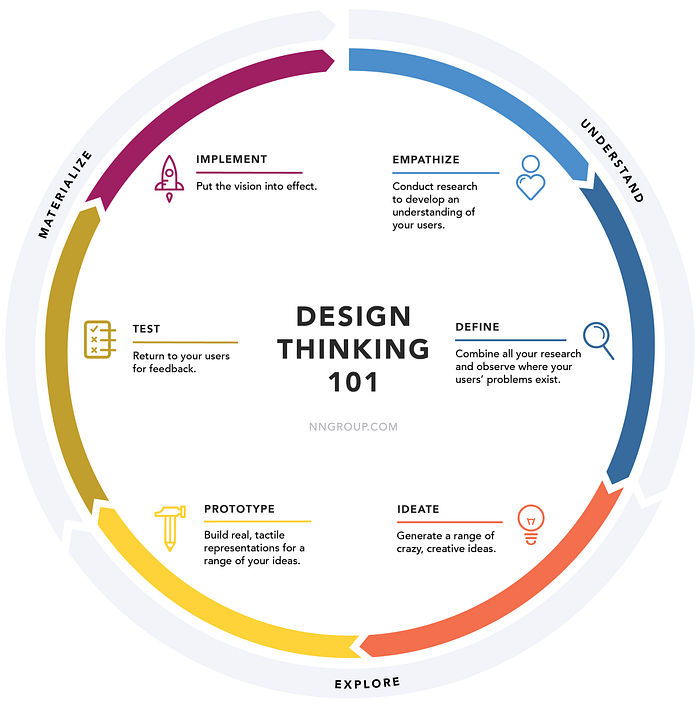

At its core, design thinking aims to solve problems by understanding the user’s needs, challenging assumptions, redefining problems, and creating innovative solutions to prototype and test.

It does this in six phases— empathize, define, ideate, prototype, test, and implement — which together represent a non-linear cycle for tackling challenges creatively and iteratively:

The concept of Design Thinking has been hailed as a guiding principle, offering a structured approach to problem-solving.

However, the implementation and understanding of the process has diverged from the original magic and effectiveness it had at IDEO. Today, Design Thinking has shown its limitations, and in fact, I’d argue that this current, hyped up implementation limits our own ability to design in innovative ways.

The Limitations of Design Thinking Today

When I was a student learning Design Thinking in my Human-Computer Interaction program, we were taught to spend most of our time in the first half of the cycle, partaking in team-wide sessions to best understand our potential user base and to ideate as many solutions as we could.

Ideation was boundless and no idea was bad. In my opinion, divergent thinking exercises is where good and innovative design truly happens.

However, today many companies that have bought into the hype cycle don’t truly understand the value of spending the time (and thus resources) on these exercises and will rush their way through. They want to proclaim they implement the process, but choose the cheapest path instead of good and innovative user-centric design as their guiding light.

Critics argue that due to this, the process has been oversimplified and commoditized, often at the expense of genuine innovation and user experience.

Linear Thinking

This growing skepticism of today’s Design Thinking was famously encapsulated by Natasha Jen’s talk titled “Design thinking is Bullsh*t”. Jen, a partner at Pentagram, criticizes design thinking for reducing a complex creative process into a prescriptive, step-by-step procedure that can be blindly applied by anyone. She argues that this cookie-cutter approach neglects the nuanced, critical thinking that true design requires.

She notes how designers in the past, prior to the digitization of everything, usually had studios strewn with gadgets, art, and objects that encouraged exploration and curiosity. The thinking behind design wasn’t so methodical nor as linear, which afforded the opportunity for “out-there” ideas to have a chance to take hold and flourish.

Financialization

As aforementioned, the ideology has been hijacked by businessmen.

The 6-phase cycle is an attractive methodology to businessmen looking to make profit from easily codified processes. This changed the metric of success from good UX and user satisfaction to eyeballs and revenue.

The UX Collective in their 2024 issue of “The State of UX” describes this as the financialization of design, going insofar to say that instead of thinking of user flows, we now focus on cash flows:

“In a world where design is used to appease shareholders and boost stock prices, advocating for users’ interests can become an afterthought.”

What tests well is often what users are already accustomed to, and what businesses want is whatever is easiest to produce and scale.

Of course, neither of those things are bad on their own, but that type of thinking cause us to miss new and unique solutions. When you always reach for the obvious answer, what you’re left with is a sterile world in which everything looks and feels the same.

Lack of Critique

In most design disciplines, receiving candid feedback in the form of formal critiques is an important part of the design process. In architecture and industrial design, this is often done in a pin-up design review.

Design Thinking is supposed to nclude quite a bit of critiquing, but the disciplined formal critiquing culture is now fading into obscurity, with user test results often serving as the only guiding light for many companies.

Just as some companies aren’t willing to account for proper product QA in their project timeline estimates, or take Scrum at face value and don’t change it to meet their individual needs, many don’t account for critique and iteration time.

Without critical analysis and debate, the process risks becoming a one-size-fits-all solution that fails to account for the unique challenges and contexts of different problems.

Introducing Absurd Thinking

In fall of 2023, I took a class called “Designing the Absurd” at New York University, taught by Pedro Oliveira. This industrial design class set out to challenge our ideas of what makes a good design and good design practice in the format of designing out-there solutions for absurd problems.

Dare to go against convention

Absurd Thinking challenges conventions. It attempts to break from the usual and critique the normal by making, doing and learning.

Unlike Design Thinking, it focuses purely on ideation and does not include a methodology or 6-phase cycle but is rather the philosophy that non-traditional approaches can lead to creative and unusual outcomes. It advocates for a shift in the paradigm of success, urging designers to explore uncharted territories, liberated from the constraints of efficiency and traditional measures of success.

The term was used by Alan Wexler in his book “Absurd Thinking: Between Art and Design”, where he famously said:

“The tool is what we use to think with. Therefore, if you want to change your thinking, change the tool.”

We’ve all heard that scarcity breeds creativity. Just think of MacGyver, a television character so well known for improvising wild, yet functional, contraptions from random objects that his name became a verb.

For Allan Wexler, he tested his own theory by designing and constructing a chair every day for 15 days. As his iterations continued on, he challenged what he thought a chair to be and played with different fabrication techniques, resulting in very unique objects:

Changing your metric of success and the tools you use, and challenging the beliefs of what you need to succeed and the problem you’re trying to solve will inevitably change how you approach your designs.

Designing for the future

Another issue is oftentimes today, we fall into trends (corporate memphis anyone?) and design based on previous experiences instead of aiming to design for future ones.

Enter Design Fiction, an ideating practice in which designers look into the future to explore and reflect upon the potential worlds they are creating. The practice of design fiction is similar to speculative design and critical design in that it uses props and design artifacts to pose questions about the future we want to design.

Unlike other types of design, Design Fiction is not seeking to solve a specific problem or create a specific and probable future, but rather explore and brainstorm possible futures through the lens of implications of our future culture. It looks at the largest possible subset of the future.

The exercise of partaking in design fiction allows us to step outside of today’s business and scientific constraints. These fictitious inventions, though not possible at the time, can help us envision our possible futures and help shape the direction we want to go in.

If you’re thinking “this seems like a futile exercise”, consider the following:

- In 1964, Star Trek introduced the communicator, a voice communication device that allowed people to communicate with others with communicators and with ships. The first flip phone was in 1996.

- In 1968, 2001: A Space Odyssey depicted a video device that resembles a modern day tablet. The iPad came out in 2010, and Apple sued Samsung over the tablet patent, and Samsung claimed that the movie invented the idea first.

- In 2015, IKEA had a design fiction exercise in which they created a catalog of IoT (Internet of Things)-driven future products. It included products like smart refrigerators that order food automatically and furniture holograms to help you create your ideal layout. Oh, and in 2017 they released their Places app to essentially do the latter with AR

All of these designs were likely seen as absurd or near-impossible at the time they were created, but they’ve all served (and are still serving) as inspiration and even blueprints for the future we’re all heading toward.

I don’t know about you, but I’m tired of reinventing the wheel regularly, whether it’s styling a button for the 500th time or being told “we want this onboarding flow to be like Y’s, but for X”.

The most exciting design problems I see today include how we’ll use new materials in architecture and industrial design, determine new design heuristics for XR, and craft the future of GUIs in a world driven by AI.

I see us as being on another inflection point, one filled with innovative new inventions ranging from new materials to new tools that will require us as designers to create new design ideologies and methodologies.

Design Thinking isn’t dead.

The ideology still holds and the methodology provides a structure and value in how it encourages critical thinking and user-centric design, but it has since been hijacked by businessmen with much of the ideation phase morphed to meet specific business needs.

Now is the time to think absurdly and reintroduce it to our processes.

Doing so is an invitation to break the shackles of convention and to infuse creativity, authenticity, and unpredictability back into the core of design. By championing the absurd, we can rediscover the essence of design, ushering in an era of genuine innovation and distinctive experiences.

Please. I don’t want every future GUI to simply be a chat box.