Habituation and User Experience (UX)

The risks of having your users habituated to bad user experiences

A previous version of this note was originally published in my Newsletter: Sperientia (Ideas for Creating the User Experience) — I invite you to subscribe.

Among the videos that I use for courses that I offer in the topic of User Experience (UX), one of my favorites and most interesting is the one that presents a talk given by Tony Faddell in TED. The topic of his talk is the importance of noticing, of observing carefully. All of the above in the context of product design. Tony takes us on a journey that, touching his personal experience as a designer from his family roots to his work at Nest, emphasizes in each anecdote the importance of noticing. The talk is one of my favorites for all its intellectual wealth and, in particular, because of the way in which Tony approaches the topic of noticing by initiating his talk highlighting the phenomenon of stopping noticing.

What happens when we stop noticing? How does our ability to not notice relate to the development of our skills and learning? How does it might against us? How does all this relate to the user experience?

Tony starts his talk with an example that illustrates the phenomenon of not noticing, that is, the phenomenon of what in psychology we call habituation: “the decrement in our response as a result of repeated stimulation”; the reduction of our ability to perceive the details of an experience, whether positive or negative. Tony tells us to get used to things like the sticky labels that are attached to the fruits of the supermarket. Fruits such as plums or peaches usually now have labels that allow their identification and marking in boxes at the time of payment. Although useful for supermarkets, for users they are a real annoyance.

Think about the following: When we want to eat the fruit, these labels usually ruin our experience when we try it. They are difficult to remove, difficult to take off from our fingers and in many cases, the process ends up damaging the fruit that we so much want to eat.

However, despite all that, Tony teaches us, we get used habituated to that bad experience. After two, three or half a dozen episodes of removing the sticky labels, we begin to resign ourselves and tolerate things to be that way. We accept the fact that there is nothing we can do; We accept that eating that delicious fruit implies going through that bad experience and living with it. We get used to it. We get habituated. We get habituated to a bad experience with a product.

The phenomenon of habituation is not bad, in fact, it is necessary to operate as human beings and survive. We getting habituated allows us to avoid being aware of the details, demanding less energy from our brain and functioning from general rules. In the case of fruit, we learn the rule of ignoring the problem of removing a label and we do it automatically, without perceiving the process and concentrating on the purpose. This ignorance of details allows us to operate in the world and do things automatically such as driving a car, swimming, riding a bicycle, dressing, reading, and hundreds more. We have internalized rules that allow us to avoid details and have dexterity in operations that are clearly complex.

And at this point we can understand a basic lesson of habituation: ignoring the details of an experience includes those details that make that a bad experience. Our brain allows us to ignore the cumbersome, the frustrating, the complex and helps us to create shortcuts and schemes that dominate the complexity of the bad experience, making the user tolerate it, live it despite the challenges it represents. In short, we get used to everything, even the bad.

And then, what does all this take us in the context of the User Experience? In general to two conclusions.

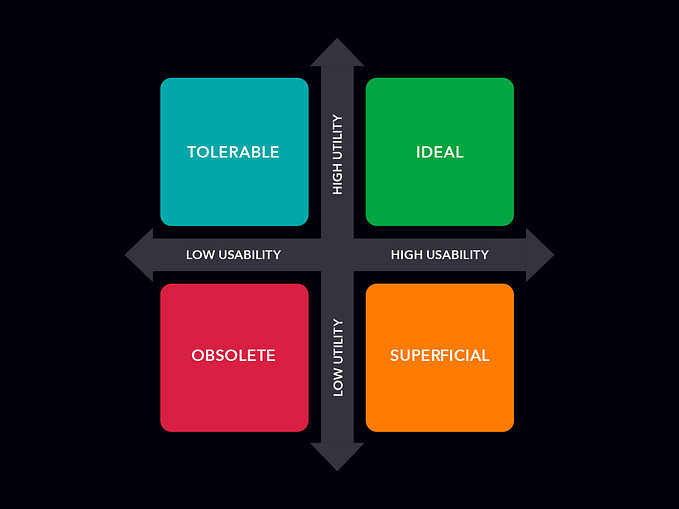

The first, that of the conceited and foolish. In this scenario, we can conclude that nothing we do to improve usability, user experience or accessibility is relevant. We can think that, if the habituation principle works well, we should wait for our users to get used to our designs, no matter if they are bad, inefficient or extremely frustrating. That is a conclusion full of myopia, but very common in many contexts.

The second, that of the wise and intelligent. In this scenario, we can conclude that our product is designed to serve user needs and that our goal is that they can be resolved in the clearest, simplest, transparent and efficient way possible. We want the user to use our product with minimal friction and frustration. And since we are trained UX professionals, our knowledge of the basics allows us to know that habituation has costs, including the aspect of cognitive load that causes us to get used to something.

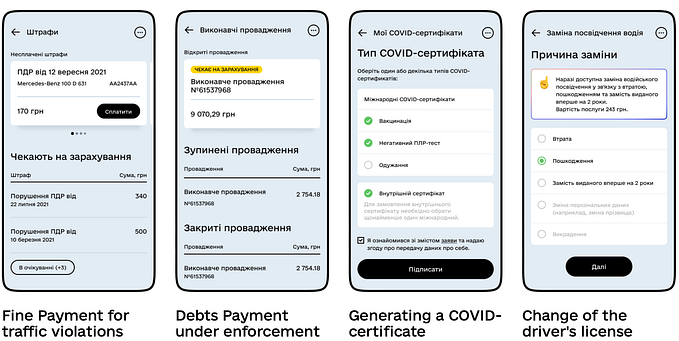

And even more, the UX professional knows that the main risk of habituation is the latent scenario of the user looking for alternatives. Yes, that is the biggest risk, the accustomed user will be looking for ways to achieve what they want in a simpler, quicker, clearer way and with less frustration. Their search will be silent, unconscious, but the brain will take you to it if it exists. It is not a matter of fidelity, it is a matter of the optimal operation of our cognitive abilities. And that’s what the user will do, she will change for another solution whenever she has an opportunity. If an alternative product or service presents a better scenario, the habituation will be abandoned and a better user experience will be welcomed.

Closing Ideas: The conclusion is that you should never trust habituation as a principle that justifies a bad user experience. If you have clients who are used to the bad experiences of your products, it is highly probable that at the slightest opportunity those people will no longer be your customers.

Your objective should be to create optimal user experiences for the customers that you serve through your digital products. Design to get used to the best experiences and always continue in the search of how those experiences can be even better.

As for the labels of plums or peaches, I do not know what you’re going to do; I already found where to buy fruits without those horrendous labels.

What do you think?

I appreciate your opinions and comments. Share them or write me

e-mail: victor.gonzalez@sperientia.com / twitter: @vmgyg

If you want to receive notifications about my thoughts, notes, workshops, and activities you can subscribe to my Sperientia Newsletter (Ideas for Creating the User Experience)

All rights reserved

Copyright © 2018 Víctor M. González

All rights reserved by Víctor Manuel González y González.

All opinions expressed here are personal and do not represent the opinion of my current or former employers, clients or partners.