How I learned to stop worrying and love user-centred design

Happy New Year everyone! How was 2019 for you? I must say it was a turning point for me at long last…

I wasn’t always like this — ebullient, enthused and engaged. There was a time, not so long ago, when I hadn’t a clue what I should do with myself, something I’d been contending with ever since I could remember. Ideas of being a doctor, an astronaut or something else cool never even entered my mind when I was a child because I was always acutely aware of my limitations as a dyslexic.

Particularly in the maths department. Even with an amazing education I never felt anything ‘click’ that would lay the foundation for the career of my dreams. After all, what would my ideal job even look like? Curbing my imagination as I had meant my focus remained myopic. A life on benefits maybe? Or a rent boy perhaps? It’s fair to say I was more than a little lost and it scared the shit out of me.

In a desperate bid to self-right like some listless, foundering Italian cruise ship I tried internships, academia and a career in communications. I’ll say this now — none of it was a waste of time, but I knew none of it was the right fit for me. As a result, I began to feel that I was the problem. I was the square peg in a sea of triangular and round holes and I’d bob around hole-lessly forevermore…

Okay, okay enough with the poor me routine. I assure you, I take absolutely no pleasure in it — it’s nauseating to even type. However, I write it with a purpose in mind not just because I have a kink for public self-flagellation. My rationale is twofold, I want to detail the unlikely path I took toward user-centred design for those of you considering a change and how your experience can help.

Before I metamorphosed into some PR shill, hellbent on controlling narratives (don’t worry I can see the irony in that statement) and palpating the truth just like Winston twisting 2 + 2 to equal 5 — I started off as an altogether different shill. Once upon a time, International Relations (IR) was my jam and I wanted a career working for international organisations and NGOs.

At least, that’s what I thought I wanted. As a subject, I found IR fascinating but its real-world applications are sparse, elitist and a little depressing. I was lucky enough to intern at several INGOs in Bosnia, Geneva and London granting me some fairly cool/unique experiences whilst also opening my eyes to the reality of the day-to-day. And from what I saw it looked like where hope went to die.

Now that wasn’t exclusively the case. But the barrier to entry was high and the work could often be soul-destroying. For example, during one internship I was compiling a report for a peace-building initiative, which cost millions of euros, but the findings were so damming they just buried the whole thing. It was the fact that no one was surprised or seemed to care that typified the experience.

But I learned a lot. Now how does this relate to user-centred design you might well be asking? Yup. Fair question. The answer is research! Arguably the most important foundation of the user-centred design process. Qualitative research and ethnographic studies, in particular, learning how to interview people and ask the right questions are both indispensable to the work I now do.

Since user-centred design focuses so much on understanding the user’s ‘needs and goals’ qualitative research gives you the tools to help you empathise with your users. I have an issue with this word ‘empathise’ being part shapeshifting reptile myself, whose biggest daily challenge is to resist blinking horizontally. I also think it’s just a bit fluffy, however, there are other techniques.

Developed by Sakichi Toyoda, the father of the Toyota Motor Cooperation, the five whys is a fantastic method for addressing the real root of a problem whilst avoiding that very un-lizardly word. I realise I might be preaching to the choir, but for those who aren’t in the know the five whys are very well summarised by the indisputable and infallible font of all knowledge — Wikipedia:

An example of a problem is: The vehicle will not start.

Why? — The battery is dead. (First why)

Why? — The alternator is not functioning. (Second why)

Why? — The alternator belt has broken. (Third why)

Why? — The alternator belt was well beyond its useful service life and not replaced. (Fourth why)

Why? — The vehicle was not maintained according to the recommended service schedule. (Fifth why, a root cause)

Despite never having used the five whys directly, it’s the inalienable simplicity of its methodology that underpins so much of what we do as designers and that’s why I believe it’s a better vehicle for understanding user-centred design, rather than the overplayed lizard-kryptonite — empathy. Briefly going back to my IR days I also learned about large-N methodologies and econometrics.

Whilst also useful, it’s better for understanding behavioural patterns — by that I mean the what as opposed to the why. Anyway, rather off-topic, let’s get back to how I ended up doing user-centred design. Due to some unfortunate health issues, I needed to help my mum and her business whilst she was away getting better. From IR to PR the last thing I thought I’d be doing was med-comms.

Queue the collective groan. Don’t worry, I won’t keep you too much longer. It’s briefly worth mentioning that I was becoming more and more lost at this time but, again, I learned a lot. The complexity of medical parlance, plus the jargon laid on by the medical professionals, meant successful med-comms campaigns had to convey complex messages clearly and concisely, often to lay audiences.

‘So what’, you might be asking. Well, to be a good designer you must be able to communicate because you’re the glue that binds stakeholders, users, devs and many others together. Think of yourself like the guy at the circus who spins all the plates — for him to be successful he has to cajole each one and it’s not easy. In other words, selling your designs is as important as creating them.

Being a good communicator is a vital soft-skill, something I had to develop as I got in touch with my inner PR lizard-man. All hail the lizard king. Med-comms then became my life for the past five years and I felt utterly trapped. As trite as it sounds I wanted to love the work I did but felt my experience had locked me into a career I more-or-less fell into. I was getting close to going postal.

It was around this time I worked at a med-tech start-up, in a small talented team of developers and designers who worked closely to get things done. Since that was how things worked I quickly picked up design tools and basic HTML, CSS and JS — discovering latent creativity I didn’t know I possessed. Hallelujah. I’d finally found something at long, long, long last. Christ. Slaughter averted 👀

What I enjoyed most about coding was that it boiled down to problem-solving. I mean, I was fucking awful at it, but I loved that about it since I’d always been a troubleshooter who gets a kick out of fixing things. It didn’t take too long for me to realise that there wasn’t enough time in the universe for me to get good at it, so before entropy snuffed out sentient life, I looked elsewhere.

It was only after chatting to an ex-UX recruiter, on a blisteringly cold February day, walking from Canterbury to Whitstable, as one does, that I learned about UX design. The fact that it also revolves around problem-solving and you don’t need to be actually good at drawing to succeed was music to my ears, since my hands are nothing but surly instruments of utter ineptitude. Fuck them.

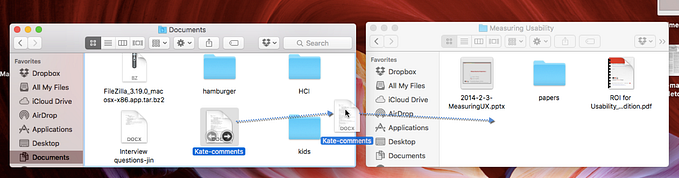

After boning up on user-centred design, reading a seemingly endless stream of books and blogs, completing the HCI Cousera course and speaking with lots of other designers I wanted in. Badly. So I chose the six-month UX/UI immersive course at the Flatiron School and haven’t looked back since. Whilst I know I’ve just prattled on about myself, I hope this is helpful for you, the reader.

What’s interesting about this profession is the multi-disciplinary nature of the people I work with. One of them has just spent 12 years in the Army. So if you are considering a seismic career change don’t doubt yourself and the qualities your experience can bring to the table. Good luck, and goodbye.