How the PAX Tire Service Model Deflated

In 2005, Michelin PAX run-flat tires were launched and soon heralded as the most important innovation in tires since radials. However, after good reviews around the physical product itself, issues in the eco-system resulted in a class action lawsuit against Michelin and partner, Honda. Here, I’d like to take a look at how a good product went bad due to faults in the supply and service network, and what we can learn from Michelin’s mistakes.

“The value proposition to the customer was clear; enhanced safety and convenience…”

The Michelin PAX run-flat tire was the result of years of engineering research and development. Michelin succeeded in launching the first run-flat that could be driven on at 55mph for another 125 miles, completely flat. The value proposition to the customer was clear; enhanced safety and convenience — you choose when and where to pull over and get it fixed without worrying about driving safely or damaging your vehicle in the meantime.

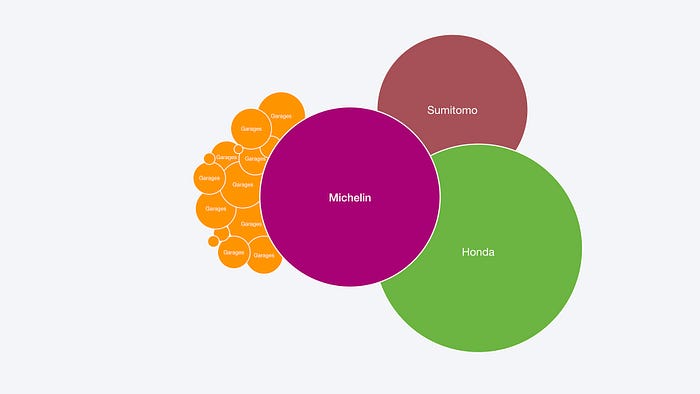

The product was big news and Michelin successfully partnered with Honda and also gained the support of their biggest competitor, Sumitomo. The PAX tire boasted such a variety of inter-company stakeholders that it was seen to have gained a life of its own. Although it was owned outright by Michelin, for many other multinationals, the project was “too big to fail”. In addition, the early user reviews were fantastic. The tires could be driven flat as intended and saved many weddings, birthdays and business meetings…

“It was a big investment ask for small businesses, sometimes too big.”

However, the reviews from the supply-side weren’t so rosy. In order to repair or replace a Michelin PAX, a repair shop needed to have the special tire-changing equipment. This equipment could cost anywhere from $3,000 to $15,000 depending on what the shop already had. It was a big investment ask for small businesses, sometimes too big. Moreover, mechanics took to chat rooms to discuss their problems with repairing a PAX (it took twice as long). This doubled the disinclination of the small businesses to invest.

The result to the user was, higher-than-expected replacement costs, difficulties getting repairs and excessive wear on the sidewalls while driving flat trying to find a service garage.

“…every product is only as good as the post-purchase experience.”

In many ways, this was a tragedy for Michelin and the PAX customers alike. The initial product to leave the factory was well liked and successful, yet every product is only as good as the post-purchase experience. But it leads us to ask, how could a business such as Michelin fail to see this potential crisis?

In short, after securing large stakeholder partners, Michelin likely used a trickle-down theory of buy-in and assumed where the big guy went, the little guy would follow.

However, they failed to take into consideration the possibility that garages wouldn’t buy-in. And if they did, they failed to calculate the potential impact on their service eco-system of this collective action by the little guy. If they had done, Michelin could have experimented with equipment leasing or training incentives in advance of the launch, but they didn’t. In the end, they paid the greatest price of all.

It is a stark reminder to us all, to always consider the components within the eco-system as the sum or their parts. No matter how small the service provider, or supply chain link in question, if your business model relies on them, they must be considered as important as your multi-national single entity partners.