How to build forms that don’t suck

A design decision-making framework with a few rhetorical techniques to help convince your stakeholders that simplicity is good for business

Filling out forms may be one of the most irredeemable experiences in the known universe (reading T&Cs is worse, but no one does, so it doesn’t count). Even the most mundane activities have enthusiasts; take extreme ironing or shipspotting, for example; Alfred Hitchcock collected train timetables and memorised all the stops on the Orient Express. But, no one ever said, ‘I’m staying home this Saturday for a session of form-filling, it’s gonna be lit’, because no one says ‘lit’ and forms suck.

Every interaction is a value exchange

Forms suck because every interaction between a user and an organisation is a value exchange, and forms are mostly the value exchange equivalent of indentured servitude; we (users) supply our time and information, and the organisation takes an outsized chunk of value (our data), in return for goods or services we are already paying for with cash.

How to solve the real problems

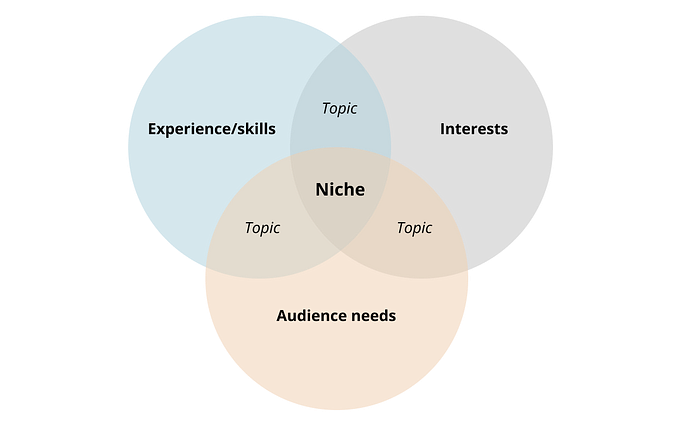

You already know that nothing will have as much impact on your completion rates as simply cutting questions. The equation is simple; fewer questions equals more completions*. The real problems that need solving are deciding what to cut and convincing your stakeholders. How do I approach the trade-offs and interdepartmental negotiation to shorten a form? I use a simple decision framework I call the Three Ds.

The Three-D s— Delete, Delay, Deliver

Jokes aside, badly designed forms can have real consequences for both the organisations that create them and end users. For businesses, the cost of bad data is over 3.1 trillion dollars per year and if you don’t know about the $300 million button already it’s a valuable read. For individuals, it can be far worse — consider that the design of medical forms causes tens of thousands of potentially life-threatening errors per year as patients are given the wrong prescriptions. The Three Ds isn’t a panacea to all bad form design, but it is a foundational tool in the form designer’s toolkit.

How to use the Three Ds — the 20-second version

Each D represents a challenge we will apply to every question in a form: Delete, Delay, Deliver. Ask the questions in order:

1. Delete

Can this question be deleted?

If yes, delete it. If not, then…

2. Delay

Can we delay asking for this information?

If yes, delay asking until after completion. If not, then…

3. Deliver (user value)

How does it benefit the user to provide this information? Explain the tangible value the user will receive on completing the form or describe the intangible value they will benefit from by providing this information.

The Unabridged Guide to the Three Ds

(more than 20 seconds but comes with examples, character assassinations, and useful tips)

The goal of the Three Ds is to create an experience that delivers business outcomes by making the task easy for your users. The best path to user ease is simplicity.

Simplicity is stupid

Don’t make the mistake (or let your stakeholders) of believing that the ease born of simplicity is a physical quality — we’re not designing a solution for carrying granite obelisks or climbing the vertiginous staircase in an Amsterdam apartment. Moving my thumb or pointer finger a few millimetres is as easy as breathing. The bit that takes effort is deciding whether or not to tap a button. It is the cognitive load of interpreting the purpose and possible effects of tapping a button, selecting a list item, or typing your name in a field that causes users to abandon forms, not tired thumbs.

The heuristic I keep in mind is — Effort is Mental

That said, simplicity is rarely achieved without a knife so we will have to cut elements. This can be hard for our stakeholders. They’re under huge pressure to deliver broad business impact, and being human, they can easily blur the broad goals and the specific. There’s no doubt we’ll have to work hard to keep everyone focussed.

Reasoning (argument) cheatsheet

For those times when our stakeholders succumb to the pressures of the big picture, here are some reminders to get them focused:

- Conversion funnels are always funnel-shaped, not chutes with 100% completion rates.

- Questions cost conversions — every additional question beyond the necessary costs the business customers (and thus revenue)

- Every question adds development effort and cost

- If we ask questions with no immediate user value users will lie to us and our data will be useless — but, sure, go ahead and fill our database with not@tellingyou.com email addresses, Jane and John Smiths, and thousands of people born this year who are all professional astronauts! (Tip: Maybe find a way to say it without blistering contempt… and try not to say it with your face — and then come back and teach me how to do it).

The cold, hard business reality is that every element in a form needs to have a rock-solid reason for existing.

This question might help convince a stakeholder or two:

How many customers are you willing to lose to get this information?

Start the journey with a clear destination

So, we know that to succeed we will have to convince stakeholders to give up things they value — easier said than done. The key, like all negotiations, is to align on outcomes. However, shared goals are not enough, without stack ranking the goals we’ll never be able to agree on the hundreds of trade-offs necessary to deliver any product; and our projects are doomed to be a crucible of conflict.

Getting aligned and primed… for trade-offs

A form’s performance drives broader business outcomes; these should be connected, not conflated. To do this, we’ll get our stakeholders into a quick workshop.

- Ask them to write on Post-it notes all the business goals they want the form to drive.

- Then, get them to prioritise them into a single file column — let them fight it out but make it clear this is on the critical path and nothing happens without this hierarchy.

- Lastly, once the dust has settled, place a Post-it next to the highest priority item with the words ‘Form Completion Rate’ on it.

- Draw a line under these two Post-its. This is now our Primary Goal and its Primary Measure of success is the Form Completion Rate.

- Explain that we aren’t ignoring the other goals and that they all have absolute value, we only need to understand their relative importance to create the optimal solution.

Now we’re ready to apply the Three Ds

Step 1: D is for Delete

Go to the very first screen the customer sees. Can this question or content be deleted, in part or in whole?

Be brutal. If we don’t ask for this information, what business metric do we know (not believe) will be negatively impacted? Who in the organisation is using this information, and how? If there’s no empirical evidence that it will have an impact, delete it. You can always run an experiment later where you add it back in. (Note: Product Manager intuition is not empirical evidence).

Here’s a form…

Over 80% of this form demands personal information that is optional for checking business name availability. 83.3% to be exact, because that second field includes two personal identifiers — first and last name. Unless the user was born in 1822 and has only just discovered the internet, they will likely assume that the company wants this info so they can spam them with direct sales messages. NB human brains always infer intent — even when it doesn’t exist.

This form has already warned me that the company intends to spam me on multiple channels, and now I’m wondering who they’re going to sell my data to. That’s a lot of friction.

So what can we delete and never ask?

- Title — we don’t need to know if you’re a Miss, Dr or Duke … ever

It turns out (I checked the govt regulations) that the remaining information (and more) is needed to register a business name.

That leaves four fields with five bits of information we need to keep. So let’s take those to Step 2 and see what survives…

Step 2: D is for Delay

Okay, so there’s a bunch of questions, input fields, images, text, dropdown lists or other elements that have justified their existence and can’t be deleted entirely, but, can they be delayed? Even for a minute or two?

Many sign-up questions (most in my experience), can and should be delayed until after the ‘Primary goal of customer conversion/acquisition’ has been achieved. Don’t let the sales or marketing teams’ passion for rich customer data sway you, the fact is that you will lose customers; it’s the reason funnels are funnel-shaped. We want our funnels to look like chutes.

Back to our business name form

We’ve killed a field — woohoo! Let’s look at what we can delay…

The fact is that while users will need to provide their full name, email address and phone number to register a business name, these aren’t necessary to check availability.

The phone number is particularly costly for conversion metrics because the impact of spam by sms and phone calls is much higher than any other channel. So let’s go ahead and delay these until they have a benefit to the user. Note: there are many cases when you should keep a contact field, we’ll get to that shortly.

Act II is always tests and trials — this story is no different

At this point, we’ll likely face counter-revolutionary pressure from our stakeholders. Depending on the culture in our organisation, individual personalities, and the current level of pressure, you’re going to need some enchanted weapons to make it to Act III. Here are two: a Spell of Enchantment and the mythical Sledgehammer of Socrates.

Enchant and enlighten your team with a story

Imagine you’re in a bar, or the monthly reading group for people who like books about obscure botanical fungi of Borneo. You’re getting a drink (it’s only tuak or tapai for the Borneo book clubbers). A super hot babe (I’ll let you choose the gender that works for you) appears next to you, looking thirsty. You think ‘I need to get to know this person. I want to have a drink with them.’ What do you suppose is going to improve your chances of that happening?

a. Introduce yourself and ask what they’d like to drink

or,

b. Introduce yourself and ask if they’d like a drink, what their phone number and home address are, whether they prefer to be addressed Ms, Miss, Mrs, or Dr, would they prefer that you contact them by email, mobile phone, work phone, home phone, SMS or ‘other’.

You get the point. We need to be single-minded about the primary goal of convincing them to have a drink with us. Once we’ve succeeded and they’re sitting, happily sipping away at the drink they wanted, we can listen for opportunities to ask all our other questions.

The same goes for forms. Ask the bare minimum needed to provide the user progress toward their goal, and once that’s achieved you can incrementally ask more, and give more.

If this fails…

Things might need a gentle tap with your sledgehammer

If you’re unlucky, some stakeholders will lose their shit and start behaving like intellectually feeble embodiments of mediocrity, they’ll abandon Reason and, depending on which flavour of fool they have chosen to be, say things like:

The Authoritarian Fool

‘As the [insert title], it’s my call. This data is important to the business so we’ll have to keep those fields in.’

How to respond to the Authoritarian Fool:

‘That sounds like something I should understand so I can do a better job as a [Designer, PM, BA, Dev — insert your title].’ Followed by:

- “Can you tell me what you mean by ‘important to the business’?”

Get them to explain how it’s used to drive key business metrics or strategic goals… if they can. And then, - “Sounds like I can learn a lot from you, can you tell me how you came to this conclusion? I’d love to understand the mechanics at play, can you point me to the data?”

Invite them to do some actual reasoning. You might be surprised and they’ll teach you something, but often you’ll get the consolation prize of their mediocrity as they avoid answering in a thousand ways. At which point you say: - “That’s a great theory, we should get some data to support it. Let’s build it your way and track performance against a second version with those fields commented out.”

Mic drop! The rest will be history.

(Note: I suggest ‘commented out’ because we need to head off the ‘too much work to build two versions’)

The Hippy Fool

‘There’s no way to know at this point so we’ll have to rely on product intuition.’

Anyone who uses the word ‘intuition’ to justify business decisions is so intellectually inept that there’s no point in asking questions 1 and 2 above, they’ve rejected critical thinking and attempted to cauterise collaboration by invoking the decision-making equivalent of astrology. Just go straight to question number 3.

The Libertarian Fool

‘As a team with autonomy over our product we value collaboration and shared ownership. Sometimes, like now, we won’t agree on the best way forward. The best thing to do is agree to disagree and move ahead.’

This one is so stupid and disingenuous that I hope I don’t insult your intelligence by explaining it, but it was so recent that I heard these words come out of the mouth of an otherwise intelligent product manager and watched as celebrated executives nodded in agreement, that I can’t leave it unsaid.

It’s a decision point, an intersection, a fork in the road, FFS. To move ahead is to select one path over another.

It’s doubly disingenuous because this person is actually saying, ‘We’re doing it my way because I say so’. They’re a hybrid fool, combining the worst of the Authoritarian Fool and the Hippy Fool without the courage to say he or she is taking over this decision, ignoring the dissenting voices, and giving up on collaboration at exactly the point at which it’s beginning to provide any value. It’s also a manipulative way to approach communication because they are invoking common company values (collaboration, team autonomy etc) to convince us why we should ignore them.

How can we respond to the Libertarian Fool?

You have options:

a) ‘I agree with you. Let’s do both versions and learn from the data’

b) ‘I agree with you. Let’s do the one with the least dev effort’ (i.e. not their option)

c) ‘I agree with you and I’m impressed by your display of selfless leadership in agreeing to forego your personal preference in this instance.’

This will hopefully get them communicating with enough respect to start collaborating, at which point you’ll need to go through all three questions as per the Authoritarian above.

Amazingly, there’ll still be some questions left to ask and things that users need to read or pretend to read (I’m looking at you, legal team, with your T&Cs checkbox bullshit). When that’s the case it’s time to employ the third D — Deliver.

Step 3: D is for Deliver (user value)

Always present questions in a way that communicates how providing the answer will benefit the user. Not explaining how the data will be used isn’t the answer, human brains hate ambiguity and will fill that intent gap with something you won’t like; BTW users probably don’t like your marketing team. However, by framing form fields as user value-creating, you can increase engagement, improve completion rates, and create a more positive user experience.

Our business name form is looking pretty good and the remaining question promises to deliver instant value to the user.

But, what if back at the Delay heuristic (Step 2) there was evidence that follow-up emails significantly increased sales? Now we’ve got to keep the email field and work out…

How might providing an email address deliver value to the user?

We can reframe the question so that it communicates the value the user will receive. That means delivering tangible value that is functionally enabled by email. For example, if we’re shipping a product we might offer tracking updates and so rather than a bland “Enter your mobile number” field, it might be, “Get tracking updates by SMS”.

However, our business name form is a little more difficult. We might offer to deliver the result of the name availability search by email, but this is an obvious extortion-like approach and is likely to trigger reactance (negative emotional arousal caused by sensing a loss of free will — i.e. being manipulated). The response to reactance is the drive to reestablish our autonomy, and the easiest way to achieve that is not to complete this form.

Instead, we could solve another customer problem, which we know of because we’ve done user research. By observing users checking available business names we know that it’s unusual to get a positive result the first time… or second or third. So let’s do this:

That’s two minutes of thinking about what might be tangible value for this form field. I’m sure you can create even better solutions to the value problem. That said, if I were designing this form I’d make the dashboard but I’d still delay the email request until after the first search.

Describe the intangible value

Often the only value possible will be intangible, but if done well, will still mitigate funnel drop-out. These include themes like security, ease, time and money savings, and even blaming the government.

e.g.

Remember, users are more likely to share information when they understand the direct benefit to them. By reframing your form fields to emphasise user value, you’re not just collecting data — you’re offering a service or benefit. This shift in perspective can transform your form from a tedious task into an opportunity for users to enhance their experience with your product or service. As an added benefit this creates a memorable brand moment and feeds into retention metrics.

And lastly, don’t make the last button say ‘Submit’ — it’s tone-deaf AF; no one wants to be reminded that corporate overlords control us with our data. How about something practical and relevant like ‘Get [the thing you came here and filled out this bloody form to receive]’?

That’s it, we’re done. Try the Three Ds and watch your completion rates soar — your stakeholders and users will thank you.

Let me know in the comments if you try the Three Ds Decision Framework and how it goes.

Want more slanderous criticism and stupid anecdotes masquerading as educational content? Send me your spam receptacle and see what happens… just don’t expect it to happen often.

Footnotes

- There are exceptions to the impact of reducing the number of questions, such as high-risk decisions like taking out a personal loan, which can benefit from more questions not less. Let’s leave that for another article.