How to design with privacy in mind

A few days ago, I started reading ‘Ruined by Design’, a great book by Mike Monteiro. In essence, he makes the case that we, as designers, have a responsibility for what we create.

So, to build on last week’s issue, where I wrote about ‘privacy’ as something that is finally getting more attention in the tech-sphere, I want to talk about how to design with privacy in mind. Because it is our responsibility as designers to do so. And to be clear, I share Monteiro’s definition of a designer:

‘If you’re affecting how a product works in any way whatsoever — you’re designing’. Mike Monteiro

First of all: Why should you care?

Well, there are some obvious economic and legal reasons to make sure you follow the necessary rules to protect your user’s privacy. Especially now, with the GDPR in effect, you could get a hefty fine — like Google, who had to pay 50 Mio Euro in France because of GDPR violations. Besides the legal aspect, you, of course, need to make sure sensitive data is secured — or you might get hacked, like so many careless companies recently and thereby losing the trust of your customers.

But even on a smaller scale and not the worst-case scenario in mind, you should think about privacy and data protection: As part of your branding.

Websites are often the primary point of contact between your company and its customers, therefore they are essential to defining your brand and to create trust. By putting an emphasis on data protection, you can build the foundation for this trust. So how do you start? What are ways to design with privacy in mind?

Privacy by Design

Back in the 1990s, Dr. Ann Cavoukian created a framework called ‘Privacy by Design’ that is based on 7 principles and seeks to proactively embed privacy into the design. Fast-forward to 2018, and it finally got the attention it deserves by being incorporated into the GDPR. In brief, it states that privacy should be built into your design as a default, that you should minimize the personal data you collect, keep it secure and destroy it when it is no longer needed, as well as be transparent to the user about why you need it and what happens to it. Also, always make sure there is no zero-sum trade-off between privacy and other interests.

With these guiding principles in mind, we can start to design our new project. Let’s go.

Before you start

Begin with how much data you actually want and need to collect. Remember: Less is better. The more you track and plan to do with the data you’re collecting, the more you need to communicate to the user, e.g. with endless declarations of data protection and cookie banners that quickly fill the whole screen. Just look at this:

Gotta collect ’em all

Do you really need all these cookies? Clearly, this is an extreme example, because free-to-read ‘journalism’ need ads to support their business model and you’re probably in a whole different situation. But still, consider how much data you actually need to provide the best experience to the user.

You don’t need someone’s name to send him a newsletter, just his e-mail address — so why bother asking? Sure, you want to build out your CRM database, but there are better ways, follow-up e-mails e.g. where the user can opt-in to provide further information. Also, sign-up rates tend to be higher, the fewer field a form has — another reason to reduce it to the minimum.

Sure, I get it. Humans are collectors by nature, thus we have a natural tendency to ask for more data than we immediately need. Better safe than sorry — maybe we will need it at some point in the future. Well, the GDPR states that you need either of these 6 legal justifications to collect data: Consent, Contract, Legal Obligation, Vital interests, Public task or legitimate interests. Most companies still rely on the latter, the legitimate interest, and argue that collecting personal data and using e.g. cookies enhances the user experience by offering a more personalized experience. But it’s a very weak argument and in many cases, I’m sure it wouldn’t hold up.

Also, get your privacy officer involved as soon as possible. Often times I see clients contacting their privacy officer after going live with a project. That’s way too late. Your privacy officer should be involved from the beginning and lay the groundwork to build upon.

So, start your project by re-thinking how much personal data you really need to collect. And remember there are two ways your users leave their data with you: voluntary by filling out forms etc (active) and passive by automated data collection through tracking scripts etc.

With that mind, let’s tackle some of the real-world topics you face in every project.

Cookie Banner

Let’s start with one of the most annoying aspects of data protection: the Cookie banner. Everyone hates it. And it tells — most of them suck. Companies who don’t want to develop their own, implement shitty third-party tools that suck even more. It’s a shame. And from an user experience as well as a branding perspective it’s more than stupid. The cookie banner — as annoying as it might be — is in many cases the first thing a user interacts with when he visits your website. So make sure it’s not a terrible experience. Again, look at this example from Ad Age, where you actually have to wait up to a minute after choosing your cookie settings for the website to render the configuration. It’s crazy.

The advertising industry managed to develop scripts that enable real-time bidding to run complex calculations in order to auction ad inventory against vendors — all within 100 ms. But to save your cookie settings, it takes several seconds up to a minute. Priorities, right?

How to fix it

There are several ways to enhance this experience and the first one is to obviously reduce the number of cookies you want to download to a user’s device. This shortens the list and simplifies the options for the user.

Then, make sure the cookie banner does not feel out of place. Put in the same effort to design it than to any other element on the website. Again, it’s one of the first things a user sees of your website — it shouldn’t look ugly and out of place like in this example:

The same goes for copywriting. Make sure your micro-copy is on point, communicates in a clear manner why you need to use cookies and what options the user has. Keep it as short as possible because you need to display it on mobile devices as well. Add a bad pun? Sure, why not. At least it shows someone cared at least a bit.

Placement

Also, think of the banner placement. Your Intercom chat bubble is hip and all, but when it covers the cookie banner, it’s just bad. Show it only after the cookie consent — how else would you know if the user agrees to the usage of such software anyway?

And please, PLEASE, don’t pop up a newsletter subscribe modal immediately after I closed the cookie banner and Intercom bubble. I don’t want to click 2–3 times before I can start using a website.

Lastly, make sure to remember the user’s choice (if he allows it, of course) and don’t show him the cookie banner every. damn. time.

Again, the ad industry manages to show me ads on Instagram for a company’s product only moments after I read an article about the bespoke company on my laptop. How hard can it be to remember my cookie settings?

If you want to learn more about how to design a great cookie consent I can highly recommend you Vitaly Friedmann’s article on SmashingMagazine.

From privacy policy to privacy hub

Ok, so you took care of the initial cookie consent. Great. But did you make sure, users can change their settings at all times?

Additionally, you’re required to allow users to request all his data you have stored, and if not automated you at least need to have a manual process in place. And then there is the need to implement an imprint (at least in Germany) as well as your privacy policy or data protection text.

Introducing: The Privacy Hub

With all that in mind, you can make a strong argument for something like a privacy hub on your website. Here, the user can change his cookies settings in detail, request his data or learn more about your privacy policy.

The hub should be easily accessible, e.g. from the main navigation or at least from the footer navigation. Make sure it’s always visible, easy to find and consistent throughout your site. Remember: It’s nothing you should hide or be ashamed of, quite the opposite.

A good starting point for this is XING’s privacy policy, which is nicely structured, uses illustrations to further guide the user and offers in-depth information for individuals who wants to learn more. The extra mile that they put in to create this platform pays off and communicates clearly how much they care.

What I would love to see is the integration of e.g. the cookie settings into the platform to make it the central place for everything privacy related at XING.

Structure and guidance

To structure the nowadays ridiculous long privacy policies, make use of accordions to allow users to quickly find the part they’re interested in. You’re required to write your privacy policy in a way everyone can understand. Go even further and ditch the legal language to give contextual explanations that directly relate to your website’s features.

Explaining why you use a certain service, e.g. Google Analytics, might also have the nice side effect that you reconsider your choices and think of alternatives.

Tracking

Talking about Google Analytics — do you really need tracking data? Don’t get me wrong: As a user experience designer, I should rely on quantitative data to test theses and validate ideas. But in many projects, I saw clients installing Google Analytics without ever looking at the numbers. Or just using the basic configuration, leaving them (and me) with not much data besides generic bounce rates and device usage. If you do it, do it right. Otherwise, just don’t use tracking software.

As mentioned earlier, many companies justify the use of tracking scripts with “optimizing the experience for users”. That’s great. But then actually do it. Use detailed event tracking to figure out if users understand your complex forms or use your search function.

Google Analytics is a blown-up piece of software that’s extremely powerful but for most projects, it’s just too powerful. A smaller, more streamlined alternative like HotJar might not only be better suited for your needs but also offer better user protection.

Technological Infrastructure

Besides tracking, you, as a website owner, are responsible for every technology, even third-party ones, that run on your website. But do you actually know how e.g. Facebook is handling the data they are collecting through your website? I doubt it. So don’t use it, at least not by default. Let the user decide if they want to opt-in for scripts that communicate ‘home’.

I don’t want to go too deep into the engineering aspects of a privacy-first website as this would be a topic on its own. But to cover the basics, you should make sure to choose a technical system that is fully GDPR-approved, e.g. by the way user data is stored, who can access it and more.

Investing in SSL-certificates should be a no-brainer as they not only build trust but also helps your site’s Google ranking.

Also, invest in security audits where external companies try to breach your system and e.g. extract data. If you think this is unnecessary and something out of movies, I again would like to recommend Darknet Diaries, a podcast about web security. Especially episode 2, where you learn how shockingly easy it was for a hacker to get access to several hundred gigabytes of children’s data because even basic security measurements were missing.

Transparency and trust

In the end, it all comes down to trust and the easiest way to achieve trust is to be transparent. By being open and communicating in a clear language you show the user that you care.

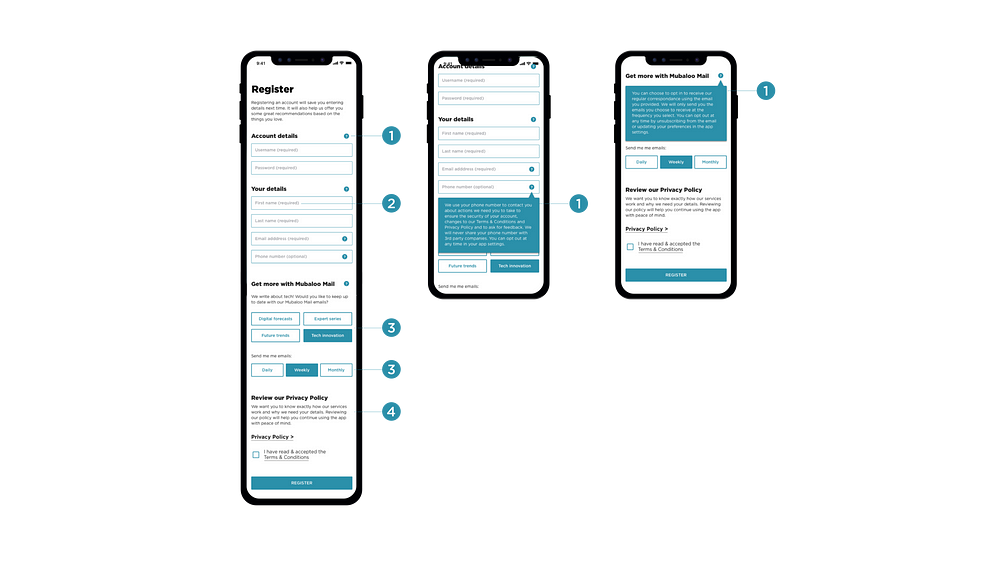

Guide them through situations where he might be uncomfortable, especially in forms where you require information like a telephone number or credit card information. A great way for this is using in-time explanations, where you explain for each and every necessary field why you need this data, how you’re handling it and where the user can change this information later on.

Conclusion

As you can see there are many ways for you to think about privacy when designing a website and most of them don’t require that much of an effort — just a change of mind maybe. We’re not talking rocket science here but the implementation of principles from the 90s.

Did you like this article?

Subscribe to my newsletter, where I send out articles like this one every Friday.