How user-centered design might be holding you back

And how problem-centered design can help.

There’s a popular diagram showing how the complexity of a project grows exponentially as the number of stakeholders increases, it looks like this:

Yet, stakeholders are one layer of a larger cake that includes things like culture, priorities, time, feasibility, and research:

The user is in that stack—but there’s a bunch of other stuff too. How do all those other factors impact the design of a product? How might over-indexing on the user be an obstacle to the ultimate success of the business?

The fundamental job of a designer is to bring stakeholders through these layers to a shared view of success while establishing alignment on the inputs and outputs of a project.

User-centered design has led us to be hyper-focused on personas, perhaps at the cost of appreciating a wider array of inputs. So, let’s look deeper at problem-centered design so that you’re better equipped to solve problems in a way that brings unanimity to your teams and business.

Always have a problem

Every good solution needs a problem and any analysis that doesn’t start with the problem definition risks devolving into a gauntlet of opinions.

Problem statements connect divergent perspectives to shared, objective goals — without them people will interpret based on emotion and feelings.

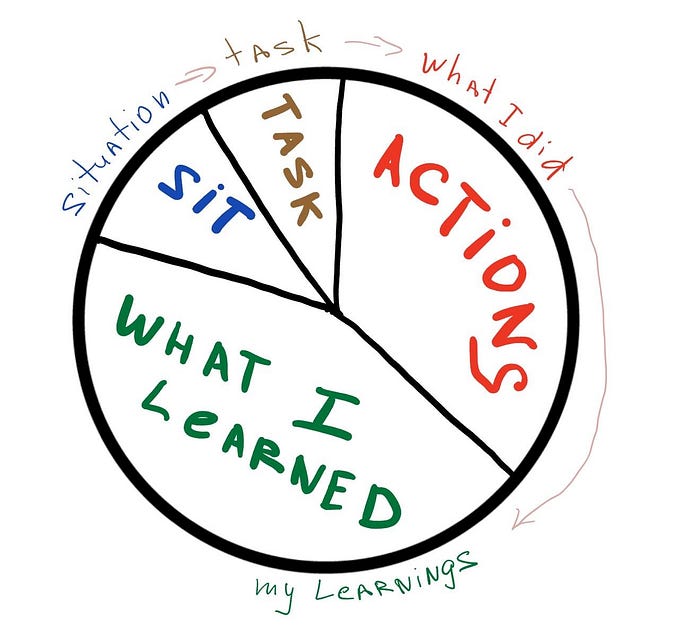

Though, what’s the best way to describe a problem and how can you be sure it’s truly being solved? Enter the Full Problem Perspective (FPP), a tool for viewing the full chain of causation for any given feature.

FPP utilizes the wildly popular jobs-to-be-done framework to turn research on users, jobs, and obstacles into actionable workstreams and success metrics.

Research tells us about our users and the jobs they need to get done as well as the obstacles preventing them from completing those jobs. Then, we form hypotheses for how to defeat those obstacles and metrics that will tell us whether we’ve been successful.

Depending on the scope, a job might map to a small feature, a big project, or an entirely new business unit — from there, user stories are derived from the work needed to validate the hypotheses while obstacles can be used to form problem statements.

An added benefit of the FPP is that it can be applied to internal stakeholders as well and the meta jobs we need to do within our own companies to be successful.

This framework lends itself well to workshops or whiteboarding exercises as the layers of the framework function as a wonderful template to fill in with sticky notes.

After forming the full perspective of a problem, it’s easier to craft statements that can be traced back to the agreed-upon truths of a project. The result is user stories or problem statements that are much less cryptic:

“As a [persona] I need [feature hypotheses] so that [job I need to do]”

It’s quite common to see pieces of the above phrase left out — for example, people often exclude the “so that” at the end. Though, remember, without the full perspective, any analysis of a solution becomes subjective.

Practice invisible design

Building UI is one of the most expensive things a development team will do. So, the bulk of a designer's work should take place before getting to UI solutions so that the team can be sure that a UI solution is needed at all.

Ways that designers can practice invisible design:

- First principles thinking — ask why until you get to the most atomic description of a problem, then think about a way to solve that

- Contextual inquiry— view users in their actual environments to see behaviors that are not observable through telemetry or video

- Paradigm shift — consider ways to leapfrog the emerging direction entirely to deliver innovating solutions that save money and time

- Harm reduction — develop solutions that introduce the least amount of negative consequences to the business relative to their potential value

As a matter of example, while leading design for Enterprise Products at Chime, I developed a Cost of Inefficiency (COI) model that’s able to project the cost per second of poor processes in our call centers.

The COI model enabled our team to spot inefficient procedures and redesign the corresponding workflows, saving our company money while not tying our R&D teams up with UI-based solutioning.

It’s rare that the design process should involve an immediate trip to a design tool. First, consider all the ways a problem might be solved so that you can ensure you are arriving at the most efficient solution possible.

Be a hunter-gatherer

Read almost any job description for a product designer and chances are it says something about dealing with ambiguity — successful designers seek out the unknown, answer it, and bring order to uncertainty.

Chances are that the half-baked PRD you got two weeks ago is the best you’re going to get unless you help finish fleshing it out: roll up your sleeves and lean into the void; ask hard questions and find good answers.

Hunter-gatherer designers…

- Seek to improve processes, communication, and use of time

- Bring people together across teams, organizations, and silos

- Have an understanding of scope, feasibility, and limits of technology

- Document decisions, timelines, and assets for posterity

- Ensure everyone is using the same nouns and verbs of a project

- Bring all the stakeholders along, ensuring alignment & unanimity

And the best hunter-gatherers spot gaps that no one else sees, working diligently to fill those voids so that the project can be successful — eventually translating the wicked web of complexities into the most useful experience possible for the user, given all available inputs.

Beyond the user

Much has been written about the value of design and how good design has been shown to be a competitive differentiator for companies. However, good design can only happen when the rest of the machine is well-oiled.

Companies like Apple seem to have nailed the design process. Though for every Apple, there are hundreds of less well-tuned companies that employ thousands of designers in the world.

The reality of Product Design is that the vast majority of designers are more likely to work in an environment that needs them to be more than just experts on the users— and it’s more critical now than ever that those designers begin practicing problem-centric design.