Introduction to Conversation Design

This post is a transcript of the first-ever conversation design workshop at Cornell University, hosted by Cornell AppDev and Google. The workshop is a subset of our larger Intro to Digital Product Design class.

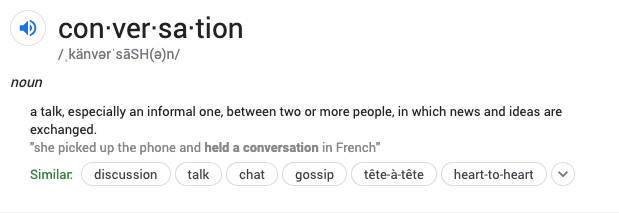

The dictionary definition of a conversation is as follows:

Broadly speaking, a conversation is any sort of interactive communication between two or more parties. Conversations are not strictly verbal — think about sending a text message, or passing notes in class. These are also forms of “conversation” where news and ideas are exchanged.

One of the fundamental mechanisms of conversation is this idea of turn-taking, where participants speak one at a time, in alternating turns. The goal is to avoid overlap, minimize silence between turns, and keep track of what’s been said in previous turns.

Let’s look at an example of where turn-taking goes wrong:

As you can see, it can be difficult for each party in a conversation to “know” when it’s their turn. If you’ve ever been in a heated debate or a meeting with multiple stakeholders, you’ll know that turn taking presents a challenge.

In real life, there is a rich inventory of cues embedded in our sentence structure, intonation, eye gaze, and body language that signals to other interlocutors when it’s their turn.

These cues are both verbal and nonverbal, which helps when you’re dealing with two living, breathing people, but is a lot more constrained when you’re dealing with a human and a digital conversational agent.

The challenge of conversation design is to design for this nuance when a human interacts with the system.

Conversation design (CxD) is about defining the interactions between the user and a conversational agent, based on how people communicate in real life.

In the way that Google’s Material Design is based on the ideas of pen & paper, conversation design is based on human voice and natural language.

Myths & Misconceptions

Myth: Conversation design is only about voice.

One of the biggest misconceptions about conversation design is that it only deals with what’s being said by either party. So, a conversation designer only has to think about the words that their agent responds with.

In reality, conversations don’t exist in a vacuum, but in the context of a broader interaction and user experience. Take a look at these examples:

When you ask Google Assistant on your phone to find you restaurants, the response that’s read out on the VUI (voice user interface) is accompanied by more descriptive information in the UI.

Similarly, when you ask Siri to set a timer, the UI displays a running countdown, rather than having Siri announce each second that passes.

These days, conversational experiences exist across platforms and devices from mobile to web to smart speakers to smart TVs. More accurately,

Conversation design exists on a spectrum that extends from voice-only to voice-forward to intermodal and more.

The interaction of asking for nearby restaurants differs if you’re talking to your Google Home versus asking Google Assistant on your phone, since for the latter, results can be visually displayed on the UI.

Taking a cross-platform approach to conversation design is useful when you think about the range of possible devices and use cases you want to accommodate.

Myth: Conversation design is just about speech recognition.

One thing that might be confusing is the distinction between conversation design and something like text-to-speech, which involves rendering text into spoken word output.

Text-to-speech is often used in screen readers for accessibility purposes, to help people with visual impairments. Beyond this, some designers have found more creative uses for it.

For example, the streaming platform Twitch has text-to-speech integration that enables viewers to engage directly with streamers. Viewers who send a donation can add a message that gets read out to the streamer and others in the chatroom. In the context of livestreaming, TTS functions as a great mode of engagement for real-time discussion and reactions.

This might sound similar to conversation design, but here’s the catch:

In conversation design, it’s not just about what people say, but what they mean.

Nowadays, advances in automatic speech recognition (ASR) mean that intelligent agents almost always know what users say, but not what they mean. A conversational agent has to not only detect what the user is saying, but understand and reply in a manner feels relevant and natural.

To design good, relevant responses, user utterances must be understood in context. A good example of where this might be crucial is a customer support chatbot, where understanding of the specific issue and responding effectively in turn makes or breaks the customer’s experience.

Why Design Conversations?

Recently, Microsoft released its 2019 Voice Report, examining the rise of voice technology and digital assistants from a market-level perspective.

Trends suggest that voice interfaces, namely digital assistants, will continue to grow, with some of the obvious ones like Google Assistant and Amazon Alexa dominating the market share.

Researchers project that the use of digital voice assistants alone will triple to 8 billion by 2023, up from just 2.5 billion at the end of 2018.

What this implies is a corollary increase in demand for researchers, designers, and engineers to define, shape, and build the conversational paradigms and best practices that govern these agents.

At times, this can lead to really good results, like this:

And at times, really bad ones:

Like product/UX designers, designers of conversational agents have a responsibility to consider the ethics and implications of their work. As a relatively unexplored field, VUI design relies on the input of diverse stakeholders, from disciplines such as design, psychology, linguistics, screenwriting, and more, to inform its approach.

Ultimately, the goals of conversation design fit with those of user experience design — to solve problems for people, to provide value and utility in people’s lives, and to spark joy and delight.

How Do You Design Conversations?

So now the meat of it — how do you actually go about designing conversation?

Here’s what the “traditional” principles of UX look like (a refresher for those of you in the Intro to Digital Product Design class):

Design deals with not only visual design, but several layers that contribute to the user experience. In order to achieve this, we employ a design process, to maximize the success and impact of a solution within a set of given constraints.

VUI design likewise follows process, but the underlying principles are slightly different, focused around human language understanding.

Here is a helpful diagram from Margaret Urban, Staff Interaction Designer for Conversation Design at Google, adapted from part of the Method Podcast.

As mentioned earlier, conversation design is based in human voice. The above framework contrasts the steps taken for our human brain to understand an utterance with the steps taken when designing a response to an utterance.

This is good to keep in mind as foundational understanding, but maybe feels a bit abstract. Let’s take a look at some more specific principles.

Guiding Principles for VUI Design

Here are a few helpful principles, with examples, for approaching good conversation design. Please keep in mind that this list is not comprehensive — there’s a lot more beyond what I cover! I’ve included some resources at the end of this post with further insights from professionals in the field.

The Cooperative Principle

Take a look at this exchange:

Carla: Do you know how to get to room 105?

John: Yes.

How would you describe John?

Now take a look at this one:

Carla: Do you know how to get to room 105?

John: Sure, it’s down the hall to your left.

The difference is that, in the latter, both parties assume an undercurrent of cooperation in the conversation. Here, cooperation operates on the basis of the amount and relevance of information provided.

By answering “yes,” John’s response is technically grammatically correct, but not helpful and uncomfortable in the context of the conversation.

We can adapt this situation to that of interacting with a digital assistant, where the cooperative principle likewise holds true:

User: Hey Siri, what’s the weather like today?

Siri: It’s hot.

Kind of funny, but ultimately not helpful. The brevity of the response can also come off as rude or standoffish, which doesn’t support brand perception.

Conversational Implicature

Here’s a nifty example from a lightning talk at Google’s 2017 I/O conference, given by James Giangola, Conversation Design & Persona Lead at Google:

Sammy: I really need a drink.

Alex: Have you been to the Eagle?

What can be inferred from this conversation? Actually, a lot:

- The Eagle serves drinks

- The drinks are alcoholic

- The Eagle is open for business

- The Eagle is nearby (driving distance)

- The Eagle is a place Sammy would probably like

Alex answers with a question, but we are able to make these inferences based on conversational implicature, the idea of a “shared library” of world knowledge that suggests the meaning of words is rarely literal or superficial.

Without specifying all of the above points, Alex is able to “listen between the lines” and convey the same intent.

Here’s another example in the context of a conversational agent:

Agent: How are you doing?

User: It’s been a long day.

Agent: The longest day of this year was the summer solstice on Friday, June 21st.

Again, this is an example of (mis)understanding user utterances in context, since the user is not literally talking about the length of the day. This can be tricky to design for, and demonstrates the nuance between natural language processing and understanding.

Defining your Brand Persona

This last one might be more familiar to those in the world of marketing. The idea of a brand persona is where a company communicates certain human characteristics, often targeted towards or expected by their consumers.

In crafting an effective brand, companies introduce a qualitative value-add in addition to their functional benefits, towards the business goal of increasing their brand equity.

Did you know? Customers are more likely to purchase a brand if its personality is similar to their own.

In the world of conversation design, this relates to the brand “voice” and how a company portrays itself. Think about a customer support chatbot — this is the first line of interaction when your customers encounter an issue, so what kind of impression do you want to leave?

Personas are a useful design tool for writing conversations. They provide a clear picture of who is communicating, evoking a distinct tone and attitude.

Wally Brill, Head of Conversation Design Advocacy & Education at Google, provides a great breakdown of the process for designing a persona, which can more or less be considered a variant of the human-centered design process:

- Understand the brand — interviewing stakeholders, reviewing brand guidelines/assets, and experiencing the product firsthand

- Understand the customer — examining the customer journey, identifying demographics, and empathizing with expectations and needs

- Understand the task — asking, “what are the main jobs to be done?” “what information do users need to know?”

- Create appropriate characters — effectively, writing a “biography” and tying your brand to a fictional character that represents your ideal image. For a clothing brand, is your character a free-spirited idealist, or a focused pragmatist? A homebody or social butterfly?

For the last step, writing a sample dialogue is a helpful way to envision your persona in action. Like a script, sample dialogues help capture the essence of the user journey and get a feel for what the user experience might be like.

Take a look at the above example from Google. Companies in the same industry can have vastly different personas, tailored to their specific customer demographics or business goals.

When writing sample dialogues, approach them like design mocks — test them out (read them) with real people to see if they make sense, think about edge cases and error states, and iterate based on feedback. The more sample dialogues you write, the clearer your sense of the brand persona becomes.

Brand personas, or more broadly brand identity, relates to the segmentation, targeting, positioning model which many companies employ as part of their marketing strategy.

In many ways, designing an effective brand persona facilitates higher-order business goals and creates value for customers, in the same way designing UI supports business objectives and user needs, as we saw in the principles of UX diagram above.

Understanding the voice of your brand, as well as the basic principles around designing for human conversation, is a solid starting point for experimenting with voice-forward experiences.

Resources

For anyone looking to dive deeper into the world of conversation design, here are some extended resources from amazing experts and thinkers worth taking a look at.

Books

Designing Voice User Interfaces: Principles of Conversational Experiences, Cathy Pearl

Conversational Design, Erika Hall & John Maeda

Designing Bots: Creating Conversational Experiences, Amir Shevat