Lessons learned from mapping the mobile gaming market

This is the story of the circumstances that led to mapping the universe of mobile game audiences.

Endings and Beginnings

When I first joined King, I took part in the development of a Hidden Object Game. A few months into testing, the game team concluded that despite a great prototype the market opportunity for Hidden Object was just not big enough to warrant further development.

Team members went on to explore new opportunities, some focusing on finding casual genres to hybridize (a hybrid is a game that incorporate elements from multiple genres, e.g. a resource management progression system on top of a switcher core).

Looking for data to better understand which genres would have an audience overlap, we turned to App Annie, looking at the affinity between audiences of different games and genres.

While audience affinity data in App Annie is useful, you have to look one by one and never really get to see the bigger picture. So we thought, what if we could map the audiences of all the games together in one big chart? That way we get to see the whole Galaxy rather than looking at one planet at a time!

A Map is Born

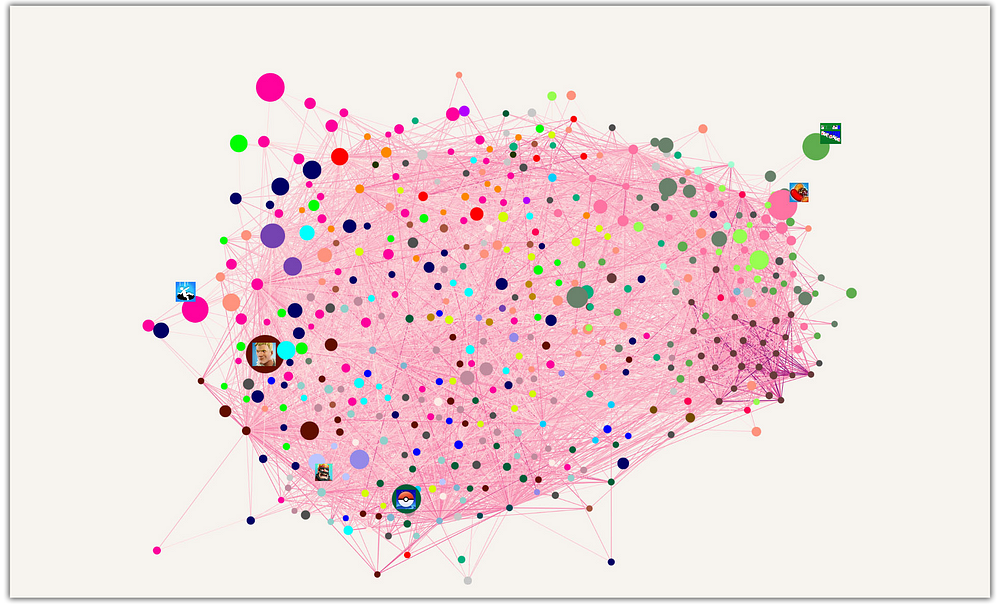

Using affinity to simulate gravity between different game audiences, we’ve created a view of the US mobile gaming market based on the audiences of the top 100 grossing mobile games and those linked to them.

In the chart below:

- Each connection represents an affinity of 5 or more (darker line = stronger affinity)

- Each node’s size represents its audience size (monthly active users)

- Each node’s color represents its genre

The map clusters audiences with high affinity next to one another, creating an explorable view of the market with different game constellations in place.

Before we get started, what does affinity mean?

Affinity between audiences is the degree of likelihood players of one game would play a different game; or put otherwise “What can we infer about a person if we know they like game x?”.

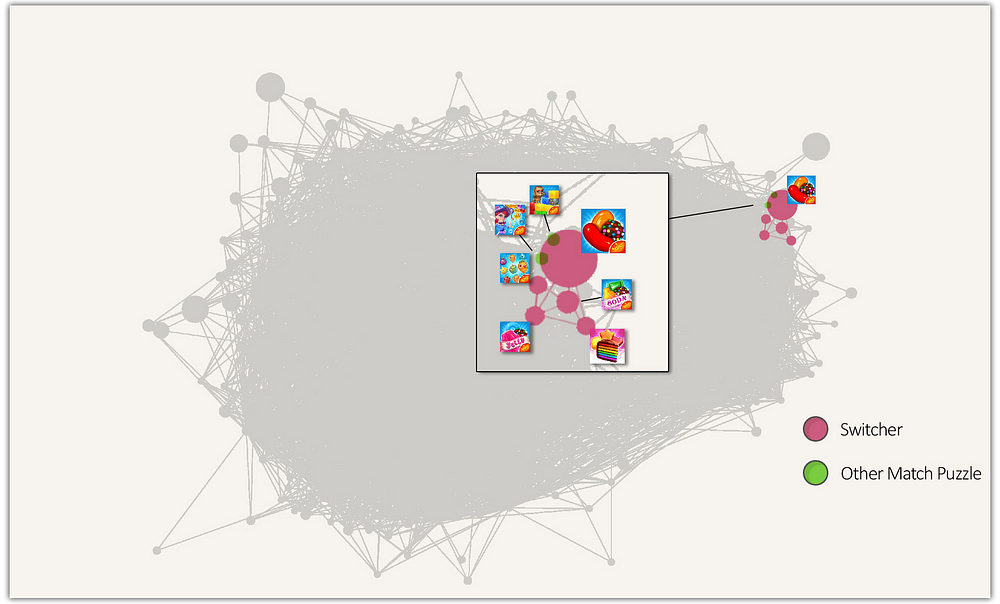

Let’s have a look at Candy Crush Saga to better understand it.

Candy Crush Saga is one of the most played mobile games. Why then is its audience not connected to many others? Why is it not central?

Think of vanilla ice cream- try and imagine the people who like it and what other flavors might they like, is it easy to draw a clear mental picture?

Probably not, it can just as easily be a plumber who likes chocolate, a businesswoman who likes coconut, a 3-year-old who likes strawberry or a heavy metal fan who likes lemon. Therefore knowing only that someone likes vanilla doesn’t add any information about their preferences other than that they might like things very similar to vanilla.

Candy Crush Saga’s audience is the same as vanilla lovers; commuting around London I see people from all walks of life playing it, and a sample of Candy Crush Saga players will be very similar to a sample of players in general. It’s not that Candy Crush Saga players don’t play a variety of other games; on the contrary, you’d find Candy Crush players playing all sorts of games.

It’s precisely the game’s popularity and the variety of other games played by Candy Crush players that makes it harder to draw conclusions as to what else an “average” player might play.

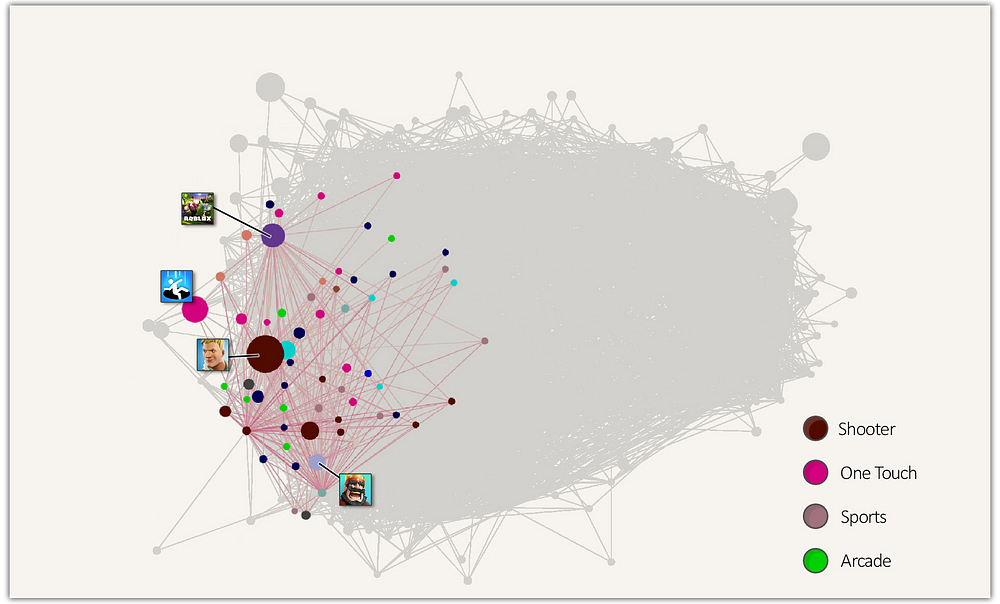

Now think about, say vegan cilantro ice cream- not as popular but it’s easier to imagine the type of person who’ll be a fan of it. Games with more distinct audiences are like that, let’s have a look at Fortnite players.

What can we learn?

Other than the obvious Shooters, Fortnite players show affinity to genres and games characterized by competition (Sports, Clash Royale); fast gameplay (One Touch); younger audiences (ROBLOX, .io games) and lighter art styles / themes.

Looking at these connections we can have a pretty good mental image of who might the average audience member be and what could appeal to them.

The Building Blocks of Games

From a high-level perspective, a game is made out of four major components: its core gameplay (e.g. First Person Shooter or Switcher); its Meta progression layer (e.g. building a character or progressing through a narrative); its theme (e.g. aliens or farm); and finally its art style (e.g. cute or realistic).

This knowledge of the building blocks allows us to think in those terms when coming up with concepts for games: “It’s a cute zombies lifestyle game with a strong co-op element!”; we can draw a pretty good mental picture of the audience who might play such a game, while still allowing for a multitude of manifestations for the concept.

Exploring the map taught us a great deal about the importance of the different components. Let’s have a look at a few examples and then see how these learnings may be implemented.

Core vs. Meta — which is key?

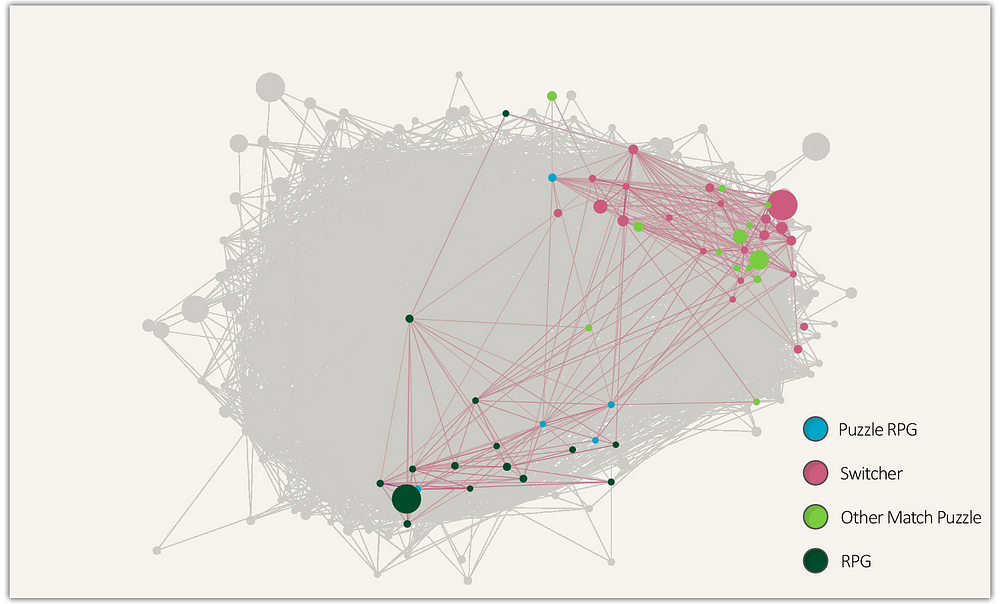

First let’s take Puzzle RPGs as an example; a genre that incorporates a core of a match puzzle with an RPG style character driven progression layer.

In this case, we see that Puzzle RPG players have more in common with RPG players than with Switcher or other Match Puzzle players; indicating the Match Puzzle is somewhat of a vanilla gaming flavor easy to incorporate with other Meta Layers.

The exception (blue dot on the top) is “Best Fiends”, a lighter puzzle RPG, that puts more emphasis on the puzzle core than the RPG meta (it also has a ‘cuter’ theme and style than most Puzzle RPGs- but more on themes later).

Still not convinced? Let’s have a look at Gardenscapes.

Gardenscapes is a popular Switcher, with a light decoration / narrative meta layer. While it was released in August 2016 it took about a year until it reached the US top 10 grossing mobile games.

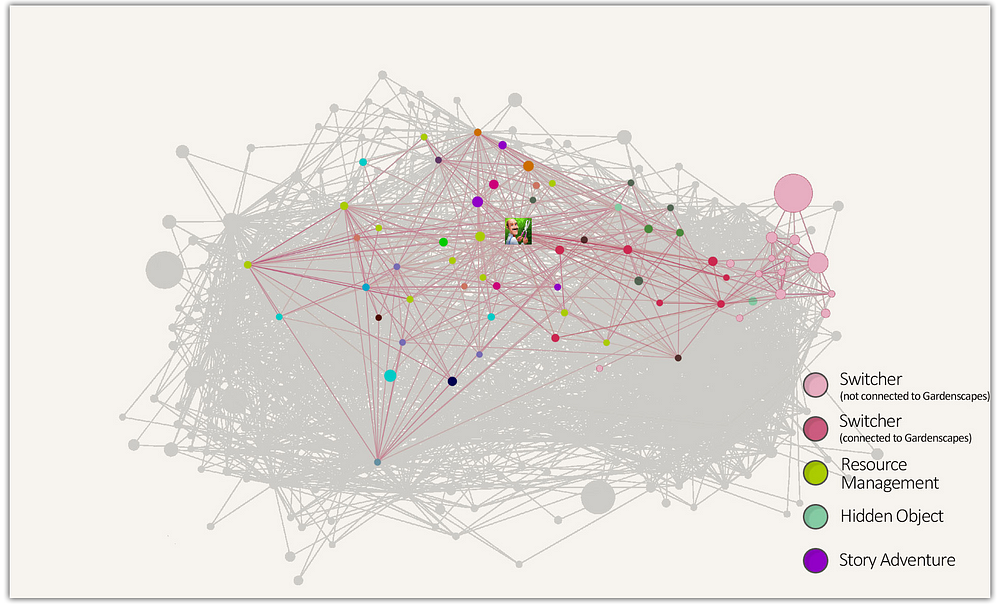

These are the audiences from which Gardenscapes’ players originated around that time.

Taxonomy-wise Gardenscapes would fit into the Switcher genre However, its players originate mostly from audiences of genres who incorporate a light narrative and customization, and it is not as connected to the vanilla Switchers’ audience; further reinforcing the importance of the meta layer.

A final word about genre and core; on a separate post I wrote about player motivation and how we measure them. We’ve found a correlation factor of 0.6 between the motivational profiles and affinity; this means a large part of observed audience preference can be explained by the meta and core.

How important are theme and art?

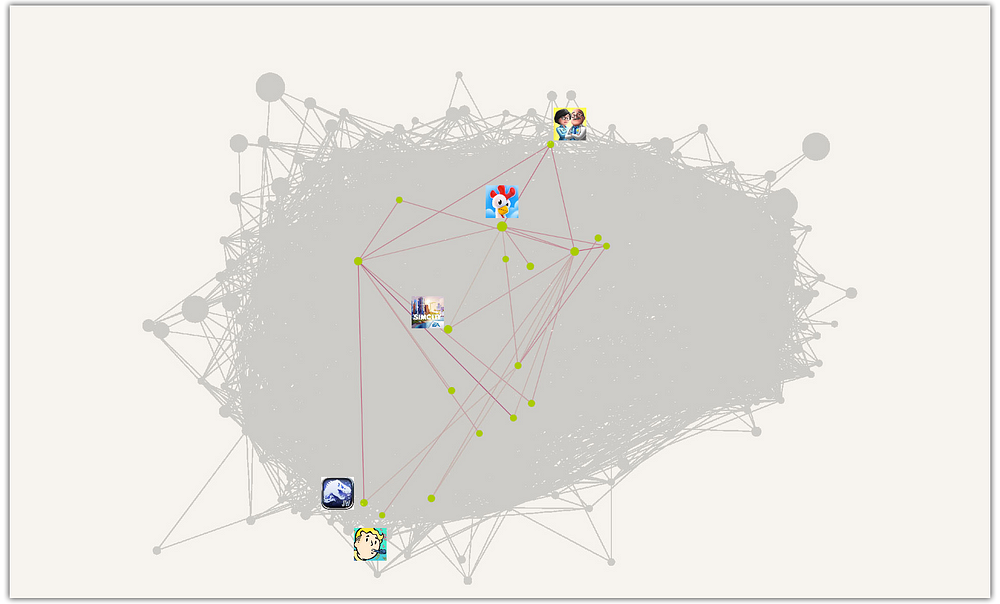

Let’s have a look at Resource Management games, a genre that’s all about getting, well um, resources and using them to upgrade buildings (or spaceships, restaurants, hospitals etc) in order to get more resources.

The different Resource Management games are not very strongly connected, and are dispersed all over the map. But clearly we see the trend going up from more mature themed games like Fallout Shelter and Jurassic Park Builder, through a relatively neutral Sim City to the lighter themed Hay Day and My Hospital.

Art style is also a bigger deal than you may think. Take the audiences of these two games: Fire Emblem Heroes, a strategy RPG and Love Nikki-Dress UP Queen, a lifestyle game focused on dressing up and collecting outfits. They may seem totally unrelated — but these games have an affinity score higher than 10 — surprising? Take a look at the app icons and think again.

Mixing It All Together — An Opportunity in the Market?

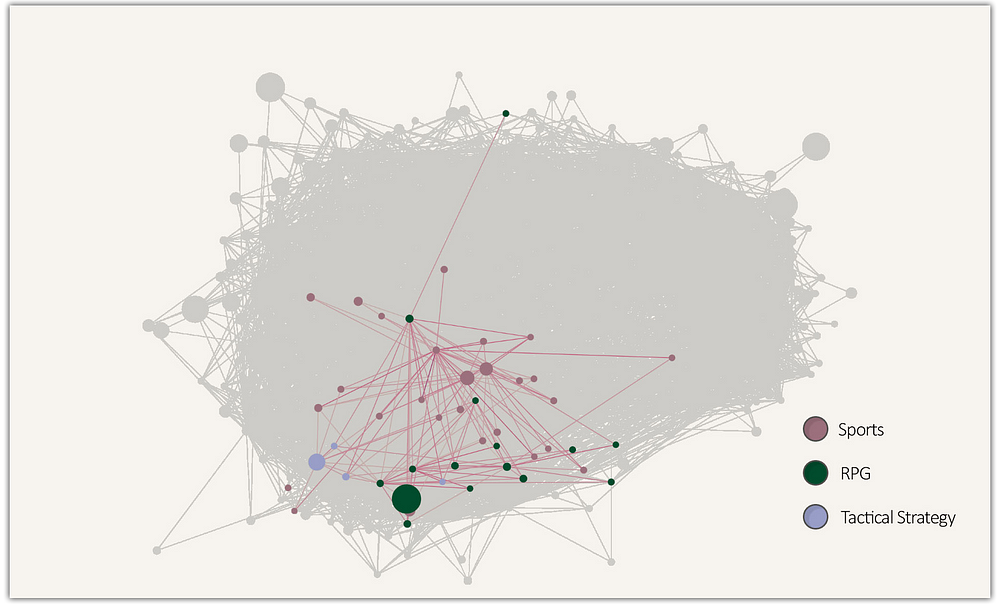

Last chart of the day:

Looking at the audiences of Sports games (e.g. FIFA Soccer, or NBA Live), RPGs (e.g. MARVEL Strike Force) and Tactical Strategy (e.g. Clash Royale) we see an overlap which suggests these genres share similar audiences.

Sports games, much like RPGs or Tactical Strategy games involve assembling a team with various strengths. However RPGs/Strategy typically have a stronger character development system with more nuances and special powers for different units.

Based on these audience connections, we may conclude there’s space for a more ‘fantastic’ themed Sports game that would allow incorporate special powers, characters and weapons with classic ball game mechanics. Creating differentiation through character a different theme would also enable a new original IP, and foregoing the big Sport brands — an entry barrier for smaller developers.

From a monetization point of view, such a hybrid sports game could tap into the potential of CCG, Gacha and vanity (customization or emotes) monetization systems.

Final Words

Using the affinity maps we’ve learned that:

- The 4 major building blocks (Core, Meta, Theme and Style) impact where a game will end up on the map.

- The Core and Genre together, as measured using a motivational profile, explain most the observed audience preference.

Some Cores are more vanilla than others, increasing the weight of the Meta layer. - While not yet measured (getting there!), there are strong indications theme and art style are more crucial than what many game makers think.

- As always, great game designers and game teams are needed to make sense and translate data into execution and success, and think why we see the audience overlaps.

Affinity data is very powerful. Many game teams struggle to fully understand their audience, especially when that audience is potentially vast! It also provides a much more fun and inspirational starting point for teams coming up with their next big thing — thinking about what will appeal to millions of players at a motivational level rather than going for the genre-du-jour.

Ishai Smadja is a Product Manager at King’s Experimentation Group, focusing on new opportunities and learning what makes players tick.