Object-oriented design for product designers

We are going to take a 10,000-foot view of the 10,000 foot-view.

Let’s talk about Object Oriented Design and how this approach can be applied to your design process.

Its origin comes from a common framework in the software engineering world. It allows engineers to break down complex relationships of data into digestible chunks for end-users to comprehend and act upon.

This concept can similarly be applied to UX design as it is a helpful framework for those aiming to simplify and display systems of data to users — for example, showing the performance metrics in marketing campaigns, deals in the sales pipeline, or a list of employees in an organization.

I recommend that this thought work is done early in your design process as it can have some implications on navigation and how information is displayed.

Definitions

For the sake of keeping this concept digestible, I want to define five key concepts that I’ll be referring to throughout this read (There are even more complexities to object-oriented design but I’ve found sticking to these concepts should get you started).

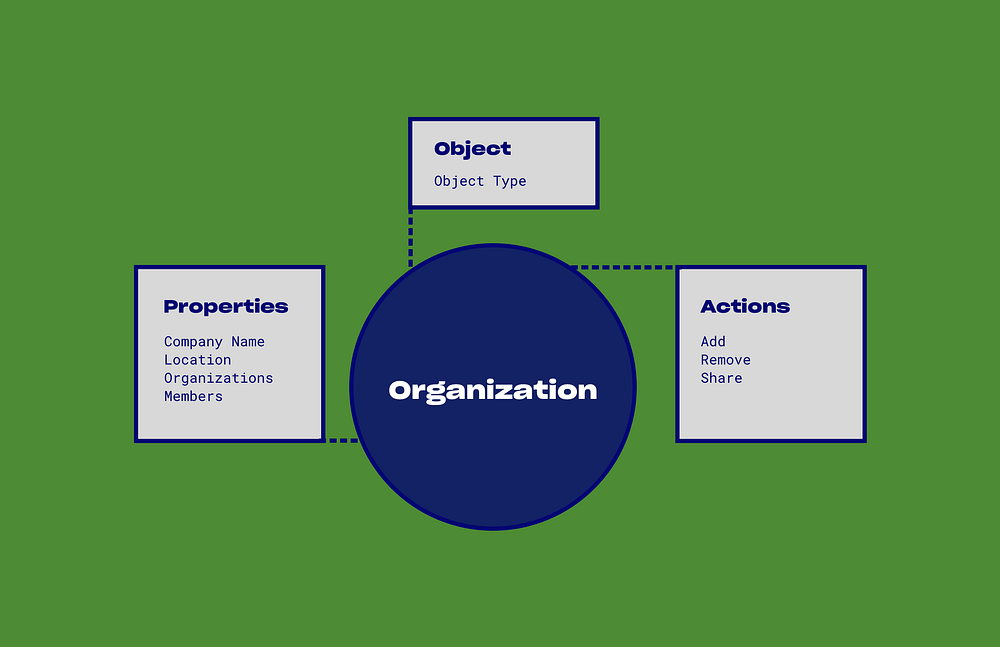

Object — Defined by its properties, and actions. An object can belong to a class or type, which is a group of objects with similar characteristics.

Type — The classification of the object you are referring to. This is commonly referred to as a ‘class’ in OOD.

Properties — A set of characteristics that an object is comprised of.

Actions — An event that you can perform to manipulate the object at a local level. This is commonly referred to as a ‘method’ in OOD.

Taxonomy — Order of object types to their relationship to each other

Identifying objects and types

Objects are grouped based on commonalities that create “types” of objects.

For example, an organization is made up of object groups of companies, and members.

Grouping objects by type allows designers to think of solutions according to themes. It allows a simple and more natural way to display information to inform a user’s next action.

Defining Properties

Identifying the properties of each object type is a great exercise to discern the difference between objects. For example an “organization object type” properties might include the number of teams, members, location, and average total experience of its members.

Meanwhile, “employee object type”s may include name, a team they belong to, years on the team, and start date.

While identifying the properties of each object type, you may also realize some do not share common characteristics and may need to be redefined in new levels or object types. This is natural. Continue defining the properties until you notice discerning patterns.

Structuring your taxonomy

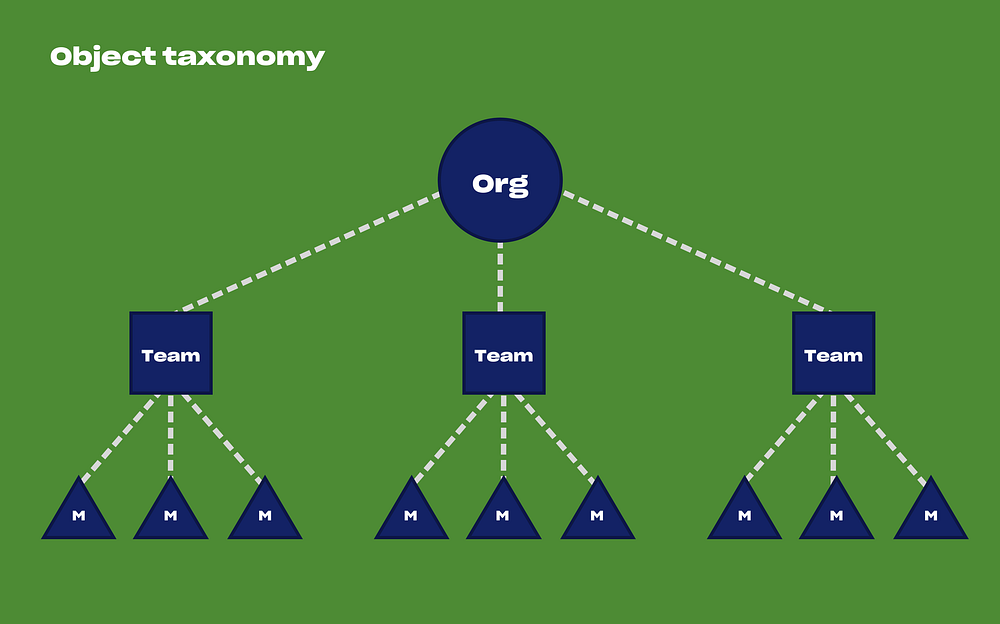

Taxonomies are important factors as they can function on an infinite scale; it can dictate what properties are displayed along with the relative actions. It’s important to recognize that not all objects are created equally and a top-level object often represents a sum of its parts.

Going back to our current example of organizational frameworks, we see the organization chart cascading down from an “organization object type” to a “member object type.” With that said, hierarchy reflects the importance of user expectations and experiences; if the information is improperly organized, it can be at the expense of your user experience.

Grouping your Actions

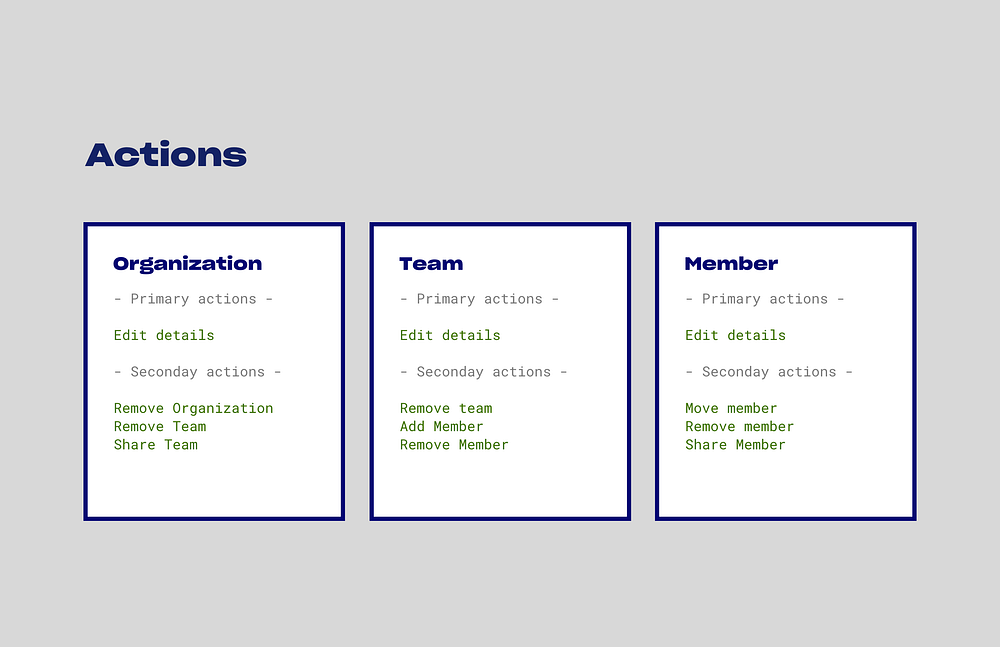

After structuring your taxonomy, group your actions according to associated object types within each level. There are numerous actions to be made on each object type. As an example, I’ve detailed hypothetical actions in the diagram below.

As you’re grouping your actions, it’s important to understand which one of these will be the primary action you want the end-user to perform. You may want this to be the most prominent one to display as secondary actions may have less emphasis — more on this in the next section.

Representation

You’ve done the work to group your objects by type, identify their properties organize your taxonomy, and designate actions. How might this work manifest itself in your experiences?

Tables are ideal for displaying data sets with a dense amount of object properties at scale. Additionally displaying object types as a card can show summaries of properties — while visually it may be more appealing, the caveat to this approach is that it may be difficult to compare and cross-reference other objects.

Each property within the object type should be filterable and sortable. This will make parsing through large sets of data manageable for your end-users. One benefit of having objects grouped together is that any column can easily be sorted by and filtered by properties.

Closing

By taking this approach to your work, you can be more effective in systems thinking by breaking down complex relationships of data into digestible chunks for end-users to comprehend and act upon, resulting in a top-notch experience.