Observing the Double Diamond process in practice

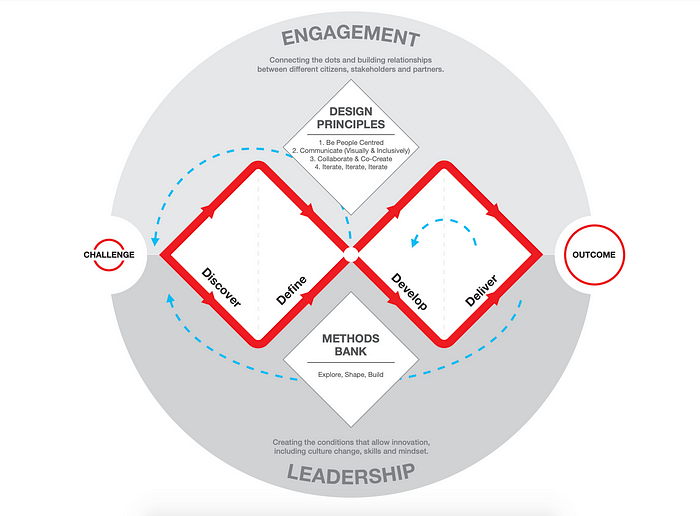

The double diamond process was launched in 2004 by the British Design Council. Afterwards, they re-assessed it and created an “evolved” version too, focusing on innovation for all, rather than design only. They’ve also added and described a list of principles covering areas as product management, human-centred processes and visual design.

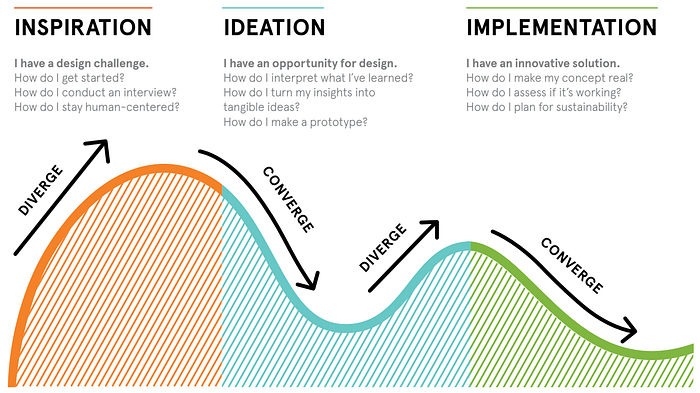

Since then it has been discussed and adapted several times, depending on who looked at it. As it’s often associated with design thinking, you have probably seen this interpretation from IDEO all across the web as well.

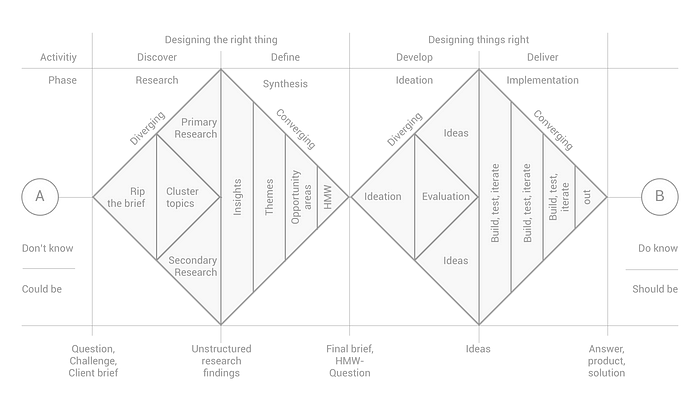

Dan Nessler had an extremely popular approach, breaking it into smaller, detailed stages. It might seem intimidating at first, but it gets quite clear once you dive into it and give it a try.

Luckily I got to experience this process, having worked in the past (and present) with people that embraced research, discovery and iterations. The diamonds were not always perfectly shaped, some steps happened to get shorter or longer, but the framework did a great job in guiding our work. I do admit that there were times when the process got butchered along the way, turning into a rather different shape without even having the excuse of an ok product release.

I believe this happens more often than we’d like to admit. Maybe there is something wrong in directly trying to apply a theoretical framework in a company? Well, John Maeda’s view on design could shed some light here. He mentioned three types. See full interview here.

- Classical design

- Design thinking

- Computational design

Now, the classical one has been practiced for decades and it usually sparks beautiful pieces of work, e.g. Dieter Rams’ products, work done in academia or institutes. It’s practitioners advocate for following clear processes and theories. Design thinking is focusing on processes and solving challenges in small or large teams within organizations. Computational design involves some sort of software or hardware, connecting people and data. Beyond the organization and its process, it entails delivering products into an ever-changing world. Sometimes these are shipped in an unfinished stage, in order to test, learn and ultimately be improved quickly, without focusing on perfection or its end state.

Many designers form their knowledge from the classical methods, getting quite frustrated when they cannot be applied to a company by the book. So, using this analogy, the Double Diamond was born and evolved in institutes and design schools then brought into the real world. The direct transition sparked either changes in the process or frustrations among people wishing to follow it closely, myself included. Then I decided to approach the issue more objectively and observe it as a researcher. This is what I have seen happening in companies that started investing in an internal UX team, trying to follow the process above (it’s also based on talks with fellow designers ).

Looking at the diagram below, I avoided symmetry on purpose, in an attempt to show the relationship between different parts of the process. The left side(envision + restrain) represents approaching goals, while the right side (develop + deliver) represents work done on them.

Envision

Companies offer services to people and get money in return. The better these services, the more people will pay for them. Making these better implies having goals, usually set by an experienced management team. I observed that it takes some time before the UX team is involved in the goal creation process itself. In the diagram, the leftmost bigger circle is the broad goal that you are briefed on.

Questions are critical in the early stages, to discover aspects that weren’t considered yet. At this point answers are rarely given immediately, but it’s a good time to probe what is set in stone, reasoning behind that and what could be explored further on.

This is also when the desk research starts. I already wrote about a few ways to ensure a solid foundation early on in the process. After investigating aspects of the initial goal, more questions come up every single time. Better clarify those as early as possible, there aren’t too many chances later. Eventually, after a few sessions, these questions and their answers help to refine the goal, as the entire team/company will start looking at multiple aspects in similar ways.

Generally, people involved in the envision stage are open and excited; everybody asks things and imagines how great it could all turn out. Now, compared to the “classical” process there is no primary research, or empathising at this stage. Very few companies invest in studies with people this early on. It’s then either up to the designers to conduct the studies independently, or rely on secondary research alone, looking at what others found in similar contexts. Nevertheless, the possible directions identified become a combination of inner company beliefs and human-centred input (from UX and others).

Restrain

Then reality knocks hard at the door. This is usually difficult to spot, especially in corporations, but sooner or later pressure starts amounting on the people responsible for delivering on those goals. What I’ve seen happening is that there is an abrupt decision-making process manifested in constrains and compromises. The possible directions, questions and desk research collected are severely affected by the company’s decision on the technology and experiences to be considered. Designers, developers, researchers and others are given a more strict path to the goal, having little to no possibility to step outside of it.

The issue is not about having constraints, it’s about how these were set in the first place. I believe good constraints make the difference between a challenge and a struggle. The real danger however, is that some people immediately push for a “Why don’t we just…” type of solution. Remember, users were not involved at all until this point; any solution picked now has a high chance of failure. Furthermore, if the same people are part of the leadership team, they have the tendency to keep going back to their own solution, until strongly proven wrong.

Develop & Deliver

Ideation, even if badly constrained is a wonderful thing. Not many people have the luxury to actually create something at their jobs. I noticed that during this time frame the team gets into the “flow”, and brings feasible, impossible, standardised, beautiful and ugly thoughts to life. However, all of them risk being absolutely terrible, since nobody is sure if the initial goal makes any sense to users. Nevertheless, these are eventually tested with people, which usually brings out a few surprises. On one hand, there are specific findings about the ideas presented to participants. These are then directly used to iterate and improve the originals. On the other hand, there is another set of findings, this time about concepts and mental models. These are the awesome findings I always wished I had 2 steps earlier, since they really question major parts of the goal. “Do people even need this anyway…they just seem to do something else…” -something that I heard fellow designers and myself say a few times.

Anyway, both types of findings are presented to stakeholders. At the same time, the pressure is mounting on, as the room waits to hear positive feedback. At the end of the slide deck, some people are in awe, while others couldn’t be bothered anyway, they have bigger issues in life. Shortly, all those themes and quotes about people’s mental models being different from the company’s model are “parked” for future improvements. Since there isn’t much time, the team forcefully converges again: current designs are quickly improved and delivered. Their efficiency is then measured directly in the product, with another promise of future improvement. I noticed that this is when people try to push for their initial solutions again. I used to have a hard time disagreeing, ending up with a similar solution, sprinkled with some UX input. Then it’s done, all that remains is to wait for the future.

How do we fix this ?

This isn’t just ranting about the state of our design practice. The point is that what we see as a “bad” process, is based on the classical view of what design should be. Yes, we must move in that direction, but not by following it blindly, and definitely not by getting frustrated if the framework isn’t adopted sacredly or immediately. We should rather identify what is the common starting point for companies just finding out about UX , look at their strengths and weaknesses and then learn how to successfully adopt a change towards a “good” process. For example, maybe the management doesn’t yet take research findings into account, but release speed is great. That means that you can still focus on experimenting with versions directly in the product and draw conclusions based on usage data as well. If there are people pushing for early ideas try to accept their input differently, not in front of the screen with Sketch opened. Walk to an “idea space”, collect them and store them for later — you need to listen to input, but not to necessarily adopt it.

Our professions are still disruptive in a output focused world which selected its processes years ago. Let’s approach it as we do any process: observe first, collect findings, then propose contextual solutions. This world will change, with or without designers and we should provide the right arguments to influence it in the right direction.

Overall, I’d extremely curious to see more designers share their current process and what they’re trying to move towards as well.