You're reading for free via Michael McWatters' Friend Link. Become a member to access the best of Medium.

Member-only story

Skeptical designers are good designers

Maybe it’s a sign of my own personal information bubble, but it seems lately I’m inundated by articles debating what design is, what designers should — or should not — do, and what even makes a good designer in the first place. And yet, in all this noise I don’t think I’ve heard anyone mention the importance and benefits of skepticism. Buckle up!

“The more we learn the more we realize how little we know.” — Buckminster Fuller

Let’s start by debunking a couple common misconceptions about skepticism:

- Skepticism is not cynicism, though the terms are often used interchangeably. Cynicism assumes a dim view of the world and, in particular, human nature. Skepticism assumes nothing, but asks for evidence in support of arguments and claims.

- Skepticism isn’t closed-minded. In fact, it’s the ultimate form of open-mindedness. The skeptic must be willing to let go of even the most cherished and closely held beliefs when presented with contradictory evidence.

Skeptical designers don’t take things for granted, or at face value. Skeptical designers do their homework, ask questions, and seek intellectual integrity and rigor.

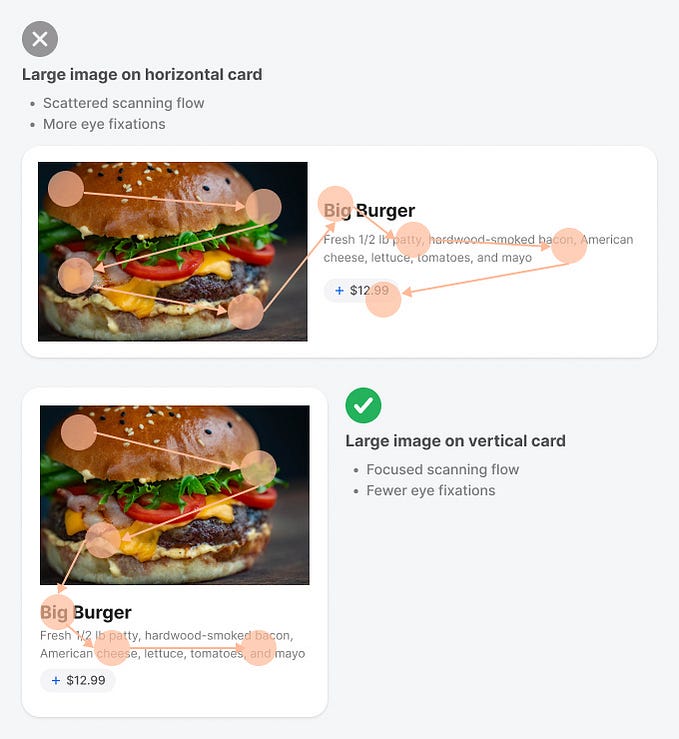

Skeptical designers know what people say and what they do may not be the same. This comes…

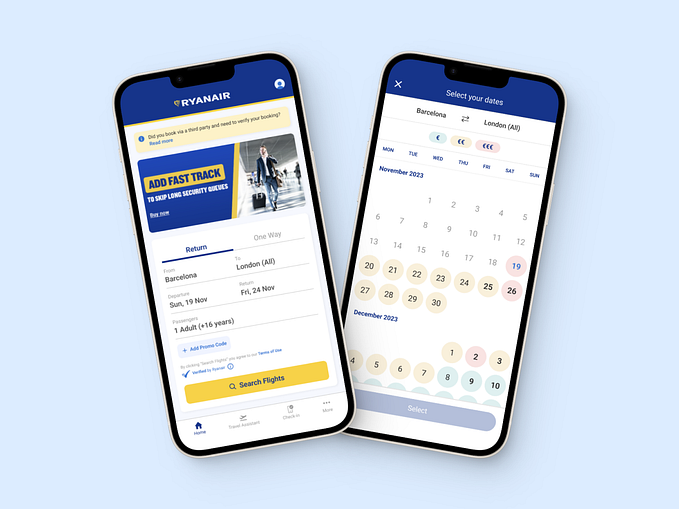

At the same time, skeptical designers are not afraid of user feedback, and welcome any way to challenge their hypotheses. For example, skeptical designers are unafraid of tests of any kind. Usability testing, acceptance testing, a/b testing are met with enthusiasm. Skeptical designers know their work will either hold up to scrutiny, or be better for the challenge. Skeptical designers consider these challenges a way to learn and improve, not as a threat or insult to their abilities.

Designers are often presented with strategies and requirements that come from people in positions of authority — clients, stakeholders, product managers, etc. Skeptical designers take these directives respectfully and seriously, but seek confirmation or testing of any assumptions or proposed solutions that seem questionable or problematic. Diplomacy is key.

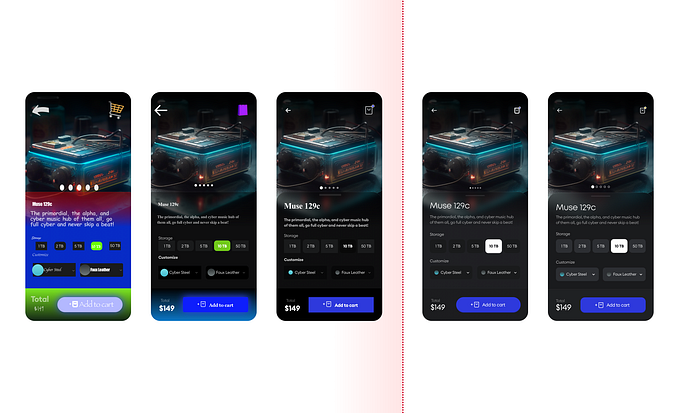

Skeptical designers are wary of design trends and fads; they understand that being current has to be balanced against the risk of becoming outdated if a trend goes out of favor. Skeptical designers are cautious when it comes to pursuing new, untested design paradigms, and they may ask to go slowly, to wait things out before jumping on the latest bandwagon.

Skeptical designers take the words of gurus and luminaries with a grain of salt. They appreciate their perspectives, but may favor the teachings of the battle-hardened who’ve had their ideas challenged in the real world.

Skeptical designers understand that challenging their assumptions, testing their work, gives them credibility. They realize that the best argument is a supportable argument, one that withstands scrutiny. They don’t ask others to believe in them because of their title, training or years of experience, but because they’ve challenged themselves and their work before drawing conclusions.

A word of caution: while skepticism is a good thing, skeptical designers run the risk of being perceived as negative or pessimistic. It’s not uncommon for people to view those who raise questions and challenge assumptions as problematic naysayers. If this happens, all the logic and evidence in the world will be rendered ineffective, and the skeptical designer will be ignored and possibly cut out of key discussions.

For this reason, skeptical designers need to learn to be ambassadors for the skeptical approach to design thinking. They need to present their questions and concerns in the most palatable and humane way possible, and at the most opportune time. They need to meet pushback with grace and diplomacy, and give great thought not just to what they’re presenting, but the way they’re presenting it.

It’s not always easy to be a skeptical designer. It takes a willingness to let go of your ego, to be proven wrong regularly and repeatedly. It means acknowledging your own weaknesses, ignorance and inabilities, and coming to terms with them. In the end, though, it’s the best, most productive way to approach design. Everything else seems surface and shallow by comparison.