Systems thinking: the key to process improvements

“Learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else.”

— Leonardo da Vinci, an Italian polymath

The Phoenix Project and The Goal

Earlier this year, I read the book, “The Phoenix Project: A Novel About IT, DevOps, and Helping Your Business Win” by Gene Kim, Kevin Behr and George Spafford. I actually listened to it over Audible. In the novel, the protagonist, Bill is an IT manager at Parts Unlimited. It’s Tuesday morning and on his drive into the office, Bill gets a call from the CEO. The novel’s plot revolves around the company’s new IT initiative, code named Phoenix Project, which is critical to the future of Parts Unlimited. We read about Bill’s despairs, discoveries and decisions over a course of 90 days from September 2 to November 28 of a given year, with a final chapter on January 9 of the following year.

Kim, Behr and Spafford have written a fast-paced and entertaining story to explain the rationale behind the DevOps movement. Some of you might be wondering, “What is DevOps?” DevOps is a set of practices that combines software development and IT operations, which had previously been treated as two separate functions with a clear handover from one to the other. It aims to shorten the systems development life cycle and provide continuous delivery with high software quality.

Kim, Behr and Spafford, who are luminaries behind the DevOps movement, in their own book published in 2013 pay homage to Dr. Eliyahu Goldratt and his novel, “The Goal” published three decades earlier in 1984. I loved “The Phoenix Project” and I had read “The Goal” more than a decade and half earlier and loved it too. Indeed, it has inspired some of my own work in business process re-engineering and improvement in working with many clients globally. So quite naturally, I found the fact that the foundation of DevOps, a set of practices for IT development, is inspired by the same principles which underpin Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints, a methodology for lean manufacturing, fascinating. Here’s a quote from “The Phoenix Project” which makes it clear.

“Any improvements made anywhere besides the bottleneck are an illusion.”

Once I found the common foundation, I started digging further. I looked into Six Sigma, Lean, Kanban and Agile. Fortunately, being variously responsible for management consulting, digital transformation, innovation, building new solutions and delivery of operations in different roles in my career, I have had the opportunity to see most of these practices in action. I have also been undertaking a course on “U.Lab: Leading From the Emerging Future” offered by MITX on edX and reading the book “Theory U” by Otto Scharmer. It all came together. I found a master key to unlock some of the secrets of better product development, software engineering, process improvement and creating a better world and self. It’s called systems thinking.

Icebergs, Traffic Jams, and Butterflies

What is Systems Thinking?

Peter Senge is an American systems scientist who is a senior lecturer at the MIT Sloan School of Management and is widely regarded as a leading authority on systems thinking. He defines systems thinking thus —

“Systems thinking is a discipline for seeing wholes. It is a framework for seeing interrelationships rather than things, for seeing ‘patterns of change’ rather than static ‘snapshots.’”

— Peter M. Senge, an American systems scientist

Without trying to get too academic about it, let me try to explain the usefulness of systems thinking through three images. Imagine an iceberg, a traffic jam and a butterfly. Hold the images in your memory. Let’s see what can we learn using these images.

Iceberg

Ice has a slightly lower density than seawater, so we see ice floating above the surface of oceans. However, because the difference in relative density is small, on average only 1/10th of an iceberg is above the surface of the water.

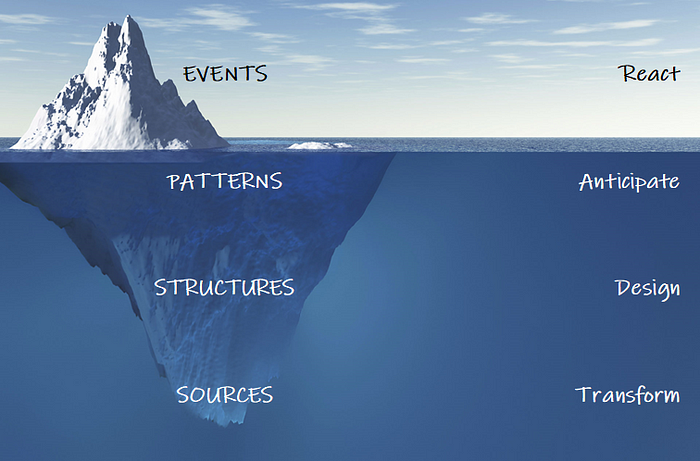

Similarly, the events that we see and react to in the world around us, are like only the tip of the iceberg above the water. There is much, more submerged beneath what we can immediately see, as shown in the figure below.

Let’s take an example. On May 25, 2020, George Floyd, a 46-year-old black man, was killed in Minneapolis, Minnesota, while being arrested for allegedly using a counterfeit bill. Floyd’s death triggered worldwide protests against police brutality, police racism, and lack of police accountability. Why?

The reason for such an overwhelming number of people coming out to protest against Floyd’s death was not a single event. What triggered it was the pattern of many such black lives not being treated as equal to white lives. People have seen and they anticipate the pattern to continue unless something is done to break the pattern. What causes this pattern to repeat?

We go a level deeper and see that it is structures which give rise to patterns. Our social structures, our economic structures, and our political structures. Structural inequality gives rise to a pattern of events such as the one that resulted in George Floyd’s death. So, if we want to make a real, lasting change, we need to design better structures. Like, Henry Thoreau, an American naturalist, and philosopher has stated —

“For every thousand hacking at the leaves of evil, there is one striking at the root.”

— Henry David Thoreau, an American philosopher

So, what gives rise to structures? It is our mental models or our sources. Where we come from makes all the difference in what we do. We can truly transform a system when we change the mental models or sources. In this regard, I recall this quote from Bill O’Brien, the late CEO of Hanover Insurance presented by Otto Scharmer in his book on Theory U. Incidentally, I have worked with Hanover Insurance as a consultant and loved it.

“The success of an intervention depends on the interior condition of the intervener.”

— Bill O’Brien, the Late CEO of Hanover Insurance

The essence of understanding systems thinking through the iceberg model is that each level down the iceberg offers a deeper understanding of the system being examined as well as increased leverage for changing it.

Traffic Jam

On January 29, 2020, TomTom, a Dutch multinational developer and creator of location technology and consumer electronics, published their latest TomTom Traffic Index. TomTom collected both real-time and historical data from 416 cities across 57 countries on 6 continents. In summary, they found that 57% of countries included saw an increase in traffic congestion with the global average congestion level at 29%. The congestion level is simply calculated as the additional time that it takes to travel in a city as compared to the baseline noncongested conditions. A 53% congestion level in Bangkok, for example, means that a 30-minute trip will take 53% more time than it would during Bangkok’s baseline noncongested conditions. I have a first-hand experience of this congestion in 4 of the top 5 most congested cities globally, including Bengaluru, Mumbai, and Pune in India and Manila in the Philippines.

Whether it is at an individual level or at a societal level, systems thinking can help us find better solutions in three ways, which you can remember through the acronym ATE as follows —

- Altitude — Imagine that you are driving through a city and you get stuck in a traffic jam. You back up your car to try another way and come across another traffic jam. You wish that you could just step back and see the city from a bird’s-eye view. Raising your altitude allows you to see the whole system or at least a larger part of the system and find the optimum solution. For example, in the figure below, if you could see the bottleneck caused by construction well ahead, you could perhaps take an alternative route. Nowadays, navigation apps have largely helped solve the problem.

- Time — While the altitude problem is solved relatively easily, the time problem is far more complex. A city planner needs to consider the behavioral change among citizens over a long duration of time caused by multiple factors. Imagine that in a city, over a period of 10 years, the price of gasoline has doubled (2X), but the price of public transport has quadrupled (4X). Let’s say that roads have been made broader and more lanes have been added. Similarly, let’s say that while the number of bus stops and train stations have remained more or less constant, the number of public parking places has doubled. You begin to see a pattern which could explain why despite more and broader roads, traffic jams have increased rather than diminishing. Systems thinking allows us to consider how a system evolves over a period of time and can lead to better planning.

- Effect — The reason that systems thinking helps us by looking at things from a higher altitude or a longer time period is that it allows us to consider the cause and effect relationship. This is just like going down different levels of the iceberg which we discussed earlier. For example, the usual approach to traffic-related problems — especially congestion — is to build more roads. However, once we consider the effect of this action, such as more roads encouraging more individual passenger cars, is it still the best solution?

We can learn about the surprisingly huge implications of seemingly small decisions by considering the butterfly.

Butterfly

“It has been said that something as small as the flutter of a butterfly’s wings can ultimately cause a typhoon halfway around the world.”

— Unknown Author

In chaos theory, the butterfly effect is the sensitive dependence on initial conditions in which a small change in one state of a system can result in large differences in a later state.

The term butterfly effect is closely associated with the work of Edward Lorenz, an American mathematician and meteorologist. In 1963, Lorenz developed a simplified mathematical model for atmospheric convection.The model is a system of three ordinary differential equations now known as the Lorenz equations. He also developed the Lorenz attractor as a set of chaotic solutions of the Lorenz system. In popular media, what is known as the butterfly effect, is the fact that a minor variation in initial conditions such as the flapping of the wings of a butterfly can change the time, path and magnitude of a tornado. The incredible coincidence is that shape of the Lorenz attractor itself, when plotted graphically, may also be seen to resemble a butterfly as shown in the figure below.

There are two important implications of the butterfly effect on how we manage people and processes in an organization to be more productive and more creative. The first is about how we should shape the initial conditions and the second about we should shape the future state.

- Alignment — Structures and processes need to be aligned towards the outcomes that we would like to see an organization produce. The result of better alignment in the initial conditions is more predictable and ever-improving outcomes. In the words of Peter M. Senge in “The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization” —

“Alignment is the necessary condition before empowering the individual will empower the whole team. Empowering the individual when there is a relatively low level of alignment worsens the chaos and makes managing the team even more difficult.”

- Creation — It is better to create the future rather than predict it. Like the butterfly effect shows, a complex system is affected by so many variables, particularly in the initial conditions, that the next best action for us after creating an alignment in the initial conditions, is for us to actively create a better future. In the words of Arthur C. Clarke, an English science-fiction writer and futurist —

I don’t think there is such a thing as as a real prophet. You can never predict the future. We know why now, of course; chaos theory, which I got very interested in, shows you can never predict the future.

In conclusion, whether it is to change the world where black lives equally matter, where we find better solutions to the problem of traffic jams or where we can make an organization more productive and more creative, we need to go down the levels of the iceberg to transform our sources and like Mahatma Gandhi, an Indian freedom fighter, and political ethicist, said —

“Be the change you want to see in the world.”