Telling stories in UX is important, Pixar can teach us a lot

8 of Pixar’s creative storytelling rules can help communicate user findings and solutions.

Why must I ‘resort’ to storytelling to present my work? A developer wouldn’t have to tell a story to sell their system architecture to the CEO, so why should a UX designer?

Storytelling is in itself UX work. A UX role is about more than just designing a product. It’s about being a facilitator of design, helping your team visualize a dream, uniting stakeholders and igniting their passion for the product. Telling a story helps you do this.

Storytelling is in itself UX work. A UX role is about more than just designing a product. It’s about being a facilitator of design, helping your team visualize a dream, uniting stakeholders and igniting their passion for the product. Telling a story helps you do this.

In 2011, a former Pixar employee, Emma Coats (who now works on personality design of Google Assistant), tweeted a series of storytelling aphorisms that were then widely circulated as “Pixar’s 22 Rules Of Storytelling.” She characterized them as “a mix of things learned from directors & coworkers at Pixar, listening to writers & directors talk about their craft, and via trial and error in the making of my own films.”

We can learn from Pixar’s process of telling a good story in presenting our UX work to stakeholders, our team, and even ourselves.

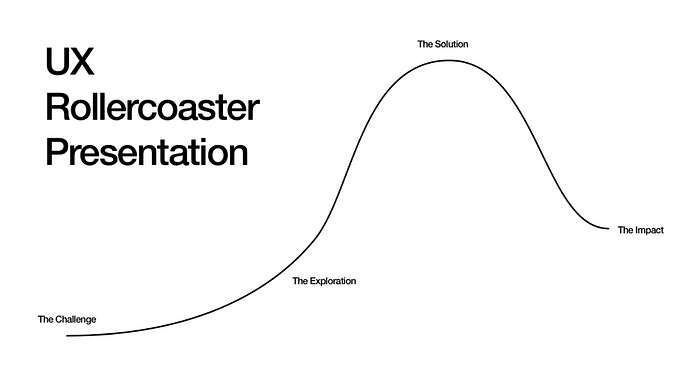

1. Once upon a time there was ___. Every day, ___. One day ___. Because of that, ___. Because of that, ___. Until finally ___.

This “story spine” originally comes from the world of improv and may apply best for a narrative, but having a template for storytelling is important to making a potentially complicated story impactful and easily digestible. It illustrates how a story is a change from an old status quo to a new one, “old world” to “new world”, through action and conflict. And the distance from “Once upon a time…” to “And they lived happily ever after” forms a mental map that helps the listener take in new information.

This approach is built around the concept that stories that are memorable will travel further and inspire greater action. Even Khan Academy uses the Pixar storytelling method to help younger kids learn the mechanics for telling a memorable story as storytelling helps improve their language skills, instills a love of reading and stirs their imagination.

2. Trying for theme is important, but you won’t see what the story is actually about til you’re at the end of it. Now rewrite.

Start with the end goals of the project, the assumptions about what will happen. In storytelling, there’s the temptation to let a story unfold without preconceived notions of how it will end. However, the challenge with this approach is that there is no clear direction — where is the story going? Similarly, when you start a new project, before you map out steps and details, always be clear on your goal and desired results. This gives you something to work toward and helps you make relevant decisions along the way.

3. Give your characters opinions. Passive/malleable might seem likable to you as you write, but it’s poison to the audience.

Don’t just highlight users’ opinions, highlight their drives, desires and goals. “Conflict” has to come from users. But this doesn’t need to be conflict at all — any interactions between design and users are the bread and butter, what makes this presentation a UX presentation. Remember that you are designing for people. Show that you talked to those people by adding quotes or at least showing some faces in your presentation. This really helps make users more real and more connected with the process.

Audiences want to see characters experiencing emotions because that’s what we’re hard-wired to find satisfying. But unless the audience knows a character’s worldview, drives and desires they can’t contextualize and interpret the character’s behavior and know how they feel for her.

4. Simplify. Focus. Combine characters. Hop over detours. You’ll feel like you’re losing valuable stuff but it sets you free.

What personas are essential to this product? What insights are irrelevant to the project at hand? There is never enough time to explain the deep thinking that goes into the small details in a UX presentation. Every storyteller wants to complete a story perfectly, but that may not always be possible. Deadlines and unrealistic standards are just two reasons why. Your project is much the same. It is more important that you finish your work, even if it’s not a perfect result, and deliver what you promised. Learn what you can from the experience so that you hone your skillset and understand potential paths for the future.

As a rule of thumb, multiple simple slides in a slide deck are better than one overwhelming slide. Use lots of whitespace and never add more than three bullet points per slide. Keeping your slides simple ensures that your audience doesn’t miss anything. In screenwriting, every scene and line of dialogue must be purposeful and push the story forward. You can ask yourself the same questions screenwriters do when deciding what belongs in the story, and what’s unnecessary fat that could be cut out.

Bonus rule: What’s the essence of your story? Most economical telling of it? If you know that, you can build out from there.

5. Finish your story, let go even if it’s not perfect.

In an ideal world you have both, but move on. Do better next time. The advice to not let the perfect be the enemy of the good is tried and true advice because it’s one of the most difficult yet crucial things for any artist to do. You do have to declare “imperfect” work to be finished in order to get things out there at all. A storyteller’s job is to know what story they’re trying to tell, and tell it to the best of their ability at the time. Once you’ve done that, you’re finished. Move on.

6. Putting it on paper lets you start fixing it. If it stays in your head, a perfect idea, you’ll never share it with anyone.

Whenever you have an idea at work, don’t just let it live in your head indefinitely, especially if you’re unable to let it go. Start brainstorming on paper and talk it through with a trusted coworker, manager, or mentor. By giving your idea a voice, you are pressure-testing and gauging its potential.

Showing how you failed with an idea is important because it helps your audience understand why your ultimate solution is superior. The idea is that you guide your audience to the same conclusion as you. Unpacking your failure shows that you didn’t just go with the first thing that popped into your head. Instead, the audience can see that you approached the problem from different angles, experimented with different solutions, and picked the best of the batch.

Bonus rule: Discount the 1st thing that comes to mind. And the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th — get the obvious out of the way. Surprise yourself.

7. Why must you tell THIS story? What’s the belief burning within you that your story feeds off of? That’s the heart of it.

The reason why you want to tell a particular story — it’s theme or message or heart — unifies all the other elements of the story around a central question. A storyteller needs to understand her motivation to tell a story — when you have a new idea, you need to know why it’s important to your organization and yourself. By knowing your idea’s place and potential, you can more clearly articulate goals and results if you decide to pursue next steps. Having a clear, concise answer to the question “why am I telling this story?” in the form of a thematic statement will enable you to always “dig deep” in the right places and stay on-point, and that will help you keep things interesting and worthwhile for the audience.

This helps show confidence and passion. There are few things more concerning to managers and other seniors than a solution delivered half-heartedly and without passion. They’ll be focusing on quality assurance: They want to be able to sign off on a design knowing that it is sound and won’t cause any problems down the line. Confidence comes from the surety that you are justified in your solution. This will shine through in your delivery.

8. You admire a character for trying more than for their successes.

Every story needs a hero. You, your product, service, or brand are NOT the hero. Your users, customers or the human beings you serve are. You are the enabler, the helper, the sidekick. You are here to serve and help your user achieve a goal and get it done, even if it is only about creating joy and pleasure. This is ultimately about the balance between seeing a character fail and seeing them succeed impacting audience appreciation of the character — not about plot dynamics. It is natural for humans to respond better to failure and conflict. If we can clearly explain the conflict or problems our users have, then we can inspire empathy, the goal of any story.

What does all of this mean for you as a UX designer?

If you are able to present your UX work solidly, you will build trust with your stakeholders. They are not only more likely to respect your work, they can enjoy your presentations and solutions. Being meticulous about creating fruitful research plans and designing amazing experiences for users should easily translate to your UX storytelling capabilities.