The cognitive cost of convenience

As oversimplification and automation erode our cognitive abilities, embracing meaningful friction may be the key to restoring it.

When I was 19, I took my first solo road trip — a 250-mile drive from Long Island, New York to Delaware to pick up my girlfriend from college — a journey that normally takes four to five hours.

At the time, I had little highway or interstate driving experience. I was nervous about the whole thing. This was before GPS or smartphones were widespread — back when the most advanced technology people had was a flip phone and a desktop computer. Finding your way meant relying on an atlas. That’s right, kids — we had to use paper maps to get around.

I still remember the day I left. I had planned my route using my father’s worn-out map book and got some advice from my girlfriend’s parents on the best route. My mother, meanwhile, was silently freaking out that I was heading out alone, with no experience driving beyond our surrounding towns.

Less than an hour into the drive, I made a wrong turn. I had confused my directions for getting onto the Southern State Parkway and ended up at Sunken Meadow State Park instead. Anyone familiar with Long Island will laugh — as those places aren’t remotely close to each other.

But I didn’t panic…well, I did a little. Fortunately, I was able to quickly retrace the route using the map of Long Island I had mentally stored. I knew if I could find 495 West — the Long Island Expressway — I’d be back on track. So I backtracked, spotted the signs for 495, and adjusted course.

Some of you might say, “Well, if you had GPS, that wouldn’t have happened.” And you’d be right. But I also wouldn’t have an interesting story — and, more importantly, a real-world example of how mental models, even a simple map of an unfamiliar area, can help us find our way. It’s a skill that remains essential even today because GPS isn’t foolproof — technology fails, and cell service isn’t always reliable.

The trade-off — convenience vs. cognitive engagement

What I’ll call the GPS Effect is part of a broader UX trend — our blind pursuit of simplicity and friction reduction is slowly erasing opportunities for deeper cognitive engagement.

Modern UX often functions like GPS, keeping users on a narrow, predefined path. It works — until something unexpected happens. If the system doesn’t anticipate a user’s goal or edge case, they’re left stranded, unable to adapt.

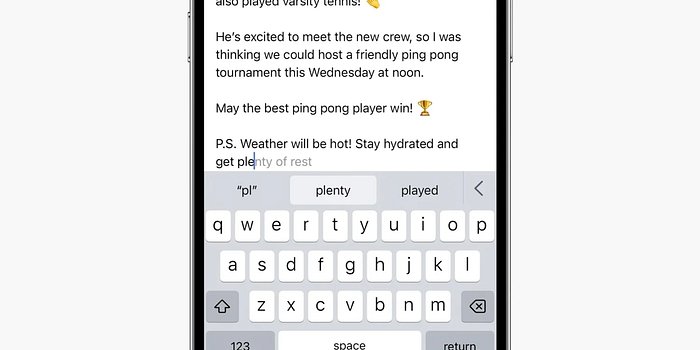

This effect extends beyond navigation. Autocomplete, for example, speeds up typing but nudges communication toward the most common expressions. Gradually, this reliance flattens language, limiting nuance and originality — just as GPS weakens our memory and spatial awareness.

The more we depend on systems optimized for convenience, the less we develop the ability to function without them.

AI is accelerating this shift. Large language models, predictive text, and AI-generated content are reducing the need for critical thinking and problem-solving.

Why struggle to write when AI can generate an answer? Why explore different approaches when an algorithm suggests the most “efficient” solution? These systems optimize for speed and ease — but at what cost?

One could argue that these tools help us go further, expanding our capabilities and removing tedious obstacles. But let’s be honest — many people don’t use them to enhance their thinking — they use them to replace it.

The case for cognitive depth in UX

Our minds don’t merely process information — they construct meaning through what cognitive scientist Steven Pinker calls mentalese — an internal language that helps us form mental models by connecting new input to existing knowledge. This ability is essential for problem-solving, adaptation, and anticipation.

Consider language acquisition. A child learning the word “dog” doesn’t memorize the letters D-O-G first. Instead, they form a mental model that links the word “dog” and the physical animal. Over time, hearing or seeing the word triggers an image, a bark, or even an emotional response. This process streamlines information interpretation, making it more intuitive and efficient.

The distinction — between surface-level memorization and true understanding — matters in UX. When interfaces are overly simplified, they can bypass natural cognitive processes. Step-by-step guidance enhances usability in the short term, but it weakens a user’s ability to develop their own mental models.

This is fine for isolated tasks. But when users need to deviate from the prescribed path, a lack of mental modeling leads to confusion and frustration. They resort to trial and error instead of intuitive navigation.

Why the future of UX needs cognitive engagement

The trend toward hyper-simplification has turned UX into a system of invisible guardrails — users are guided through interactions without necessarily understanding how or why things work. This creates a smooth experience but limits autonomy.

Think about learning to drive. Many beginners start with an automatic transmission because it removes complexity, allowing them to focus on steering and road awareness.

But if they never learn how a manual transmission works, they miss out on a deeper understanding of engine behavior and full control in all conditions. They can still get from point A to B, but their knowledge remains surface-level.

The same applies to UX. Instead of eliminating all friction, interfaces should embrace progressive depth — starting simple but allowing users to gradually build competence.

This strategy is sometimes called progressive disclosure — a design approach that gradually reveals more complex information or features only when users need them, so they aren’t overwhelmed by too many options at once.

Interestingly, the effect of reduced cognitive flexibility isn’t limited to end users. Designers themselves can become entangled in technologies that oversimplify essential complexities.

In fact, I recently explored this idea in an article that sparked some strong reactions— arguing that designers’ over-reliance on no-code tools like Figma has weakened their critical thinking skills — making them less attuned to the digital media they design for.

Of course, simplicity has its place. Removing unnecessary complexity is crucial for efficiency, usability, and accessibility. But the goal shouldn’t be to eliminate all cognitive effort — only unnecessary friction. Thoughtful UX doesn’t just make things easier — it makes experiences more enriching and empowering over time.

How do we fix this? Designing for cognitive depth

If UX prioritizes frictionless experiences at the cost of user autonomy, the solution isn’t to reintroduce unnecessary complexity but to design systems that encourage deeper engagement when needed.

Some of the best-designed systems already do this naturally. For example, Wikipedia doesn’t just provide a quick answer — it invites users to explore interconnected ideas through internal links, forming a deeper understanding of a subject. Alternatively, Google’s Advanced Search offers a streamlined starting point but reveals greater control for those who seek it.

Even IKEA’s self-assembly model turns effort into an advantage — by assembling their own furniture, customers develop a stronger connection to the product, reinforcing both understanding and perceived value.

However, it seems AI is moving in the opposite direction. Most AI-driven tools today prioritize instant solutions over long-term comprehension.

Chatbots answer questions immediately, autocomplete finishes thoughts before they fully form, and code generators eliminate the need to understand syntax — all reducing effort but also stripping away the opportunity for learning.

But what if AI did more than just provide answers? Imagine a design assistant that doesn’t just suggest improvements but challenges users to think critically — explaining why certain choices work based on cognitive load principles and prompting them to refine their decisions through an iterative process.

Or a coding AI that, instead of simply completing a function, nudges developers to predict potential errors, guiding them toward the solution rather than handing it over outright.

The goal shouldn’t be to eliminate every cognitive challenge — only the unnecessary ones. Thoughtful UX design, including AI-driven interfaces, should preserve engagement where it matters, guiding users toward understanding rather than just handing them solutions.

Cognitive depth — the missing ingredient in UX

Cognitive depth isn’t about making interfaces or engagement harder — it’s about making them more meaningful.

Great design should empower users, not just guide them. Like learning to navigate without GPS, an interface that broadens mental models, encourages exploration, and promotes problem-solving to help users develop confidence and adaptability. When we remove all friction, we risk leaving people directionless the moment they stray from the path.

Because in the end, a frictionless world isn’t always a better one. If I had GPS on that first road trip, I might not have gotten lost — but I also wouldn’t have learned how to find my way. Sometimes, the best designs are the ones that make us think.

Don’t miss out! Join my email list and receive the latest content.