The current state of UX accessibility in public transportation

The wind pushes back against your face and you feel the rush of the oncoming train. Monotone hums minimize as the train comes to a screeching halt and its doors hiss open. You are visually impaired and cannot see the doorway. Sound comes from the right, so you carefully step onto the train and feel the heavy shuffling of a crowd of feet thumping through the floor. As the doors close, the warm air closes in around you, along with elbows, shoulders, and a few sources of heavy breathing through face masks. Resisting the urge to scream, “No way Jose. Please LET ME OUT”, you reassure yourself, “Just 25 more minutes, just 25 more minutes,”. Anxiously, you smooth down the corners of your face mask and hope for the best.

Breaking down the genre

Public transportation applications are necessary for people who need safe, affordable ways to commute by bus or or train during the COVID-19 pandemic.

User interface design patterns created for accessibility are the outcome of solutions that aim to meet the needs of the physical challenges that users experience and live with. This example of genre emergence offers a new experience to users that allow them to live differently (Miller, 10) with more confidence, ease, and security.

In this article, I will explain and analyze the effectiveness of user interface design patterns that are designed to make digital interfaces more accessible. Specifically, I intend to explore design patterns created for accessible experiences in transportation applications.

Understanding the situation

We are currently living in the midst of a global pandemic where people are constantly challenged to adapt and compromise to stay afloat.

Passengers ages 14 to 65 who have no choice but to take public transportation to commute because they do not have the luxury of working from home or cannot afford private modes of transportation. Many people do not have the privilege to rent or own a personal vehicle or pay ride-sharing/private transportation service fees. Examples of the user group include individuals who are mobility/hearing/visually impaired, low-income individuals, and students.

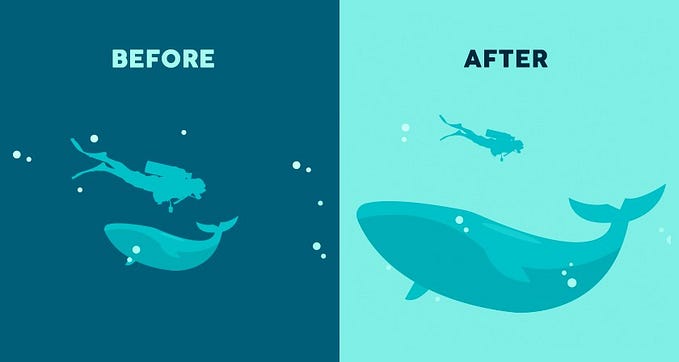

While some train cars are congested and filled to the brim with people, neighboring cars may be empty with available seats. I see an opportunity to visualize a solution that has the potential to make a meaningful difference in people’s daily lives. Equitable accessibility design creates a way to give passengers confidence and control throughout the process that leads up to the moment where they make the most critical safety decision that can save or endanger their health: where to sit.

Setting the scene

According to the World Health Organization, right now, over 5% of the world’s population (around 466 million people) have hearing loss (432 million adults and 34 million children) (WHO, 2021).

In a world where we are constantly on the move, it’s easy to overlook the possibilities that people around you may have invisible disabilities especially throughout your daily activities that may be routine for you but a challenge for someone else. Public transportation services that have applications are required by law (Title II of the ADA, American with Disabilities Act issued by the U.S. Department of Transportation) to include accessibility features; however, these features are often hidden and come secondary to the main interface of the experience.

Although most existing features address the needs of individuals who are hearing or visually impaired, not all features are effective or convenient for some users. Throughout this article, I want to explain and analyze the effectiveness of existing user interface design patterns that are designed to make digital interfaces for public transportation more accessible.

Why equitable design?

There is a difference between equity and equality. While design centered around equality ensures that most general user needs are met, it fails to address the diverse range of needs that some users need. Thus, equal design does not necessarily mean that everyone is included or that all users can access it. However, equitable design targets specific users’ needs and aims to focus on giving users the tools they need to live comfortably and confidently through inclusive design.

A universal language

Accessible design allows you to reach a large audience of users, regardless if they have a disability or not. It is important to consider how some design features may function differently across cultures. In “Genre Innovation: Evolution, Emergence, or Something else?”, author Carolyn R. Miller observes the unpredictability of the “modification and propagation of cultures in linguistic and cultural change” (Miller 9). Accessible design transcends language barriers because it creates accessible solutions that target specific needs for individuals with disabilities across the world.

Pattern Analysis

There are many apps that successfully help users plan daily trips such as Google Maps, BART, Transit, Citymapper, or Moovit. However, these competitors bury accessibility features deep within settings. There is a need to place accessibility features at the core and forefront of transportation app design. In order to meet the needs of those incapable of private travel, a focus on mobility and accessibility makes safe and inclusive transportation possible.

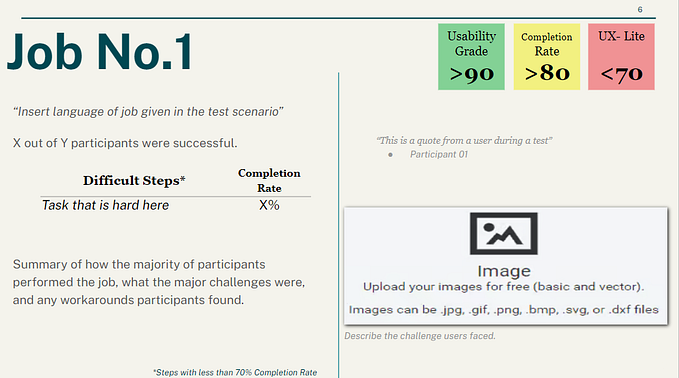

📍 Location of Settings

- Application’s Settings are located at the top right on the Home page. This is an effective UI design pattern because it is intuitive and efficient.

— Citymapper, Transit - Requires the user to access Settings after clicking a previous item on the Home page: Profile or Menu. This is not an effective UI design pattern because requires users to take an extra step to access Settings. Users with accessibility needs require tools to be in an intuitive and easily accessible location.

— BART, Moovit

📍 Location of Accessibility tools

Number of clicks needed to find accessibility tools:

Location of accessibility tools:

- BART

3 clicks

— difficulty with finding accessibility tools (under settings and notification settings)

— buried within the Profile

- Citymapper

3 clicks

— Unclear if accessibility tools is in Adjustments or Transit (may take extra clicks to explore both pages to find accessibility tools)

- Transit

3 clicks

— Users must scroll through the long list of options to come across the accessibility tools located in Notifications and Siri Voice Commands.

- Moovit

4 clicks

— Accessibility tools can be found in Notifications and Accessibility within Settings which is located within the Menu.

📍 Sensory feedback and information

- Auditory — All applications had an auditory feature, most commonly presented in the form of projected notifications and updates.

- Visual — None of the applications has features that enlarge the text for users.

- Physical — Most applications have a feature that gave users an estimate of the amount of time they may need to travel on foot.

What the Genre Conventions Reveal About the Scene & Situation

The user’s transportation experience depends on the effectiveness of these features to guide the user through planning their trip, the platform experience, and the ride.

Most transportation applications meet accessibility requirements, but accessibility needs still remain. Some transportation applications have effective auditory solutions, but may be difficult to access for users who are visually impaired. On the other hand, some transportation applications’ accessibility tools are easily accessible but are insufficient for users with hearing impairment who may have trouble navigating the riding experience.

We can’t satisfy all users, but with each advance in UX research we gain a better understanding of how to tackle the root of the problem and create solutions that go beyond a single solution. Diversity is a fact, but inclusion is a choice. Rather than a single solution, a multitude of inclusive solutions may be able to meet the vast array of diverse user needs.

However, experiences can vary depending on the context of each user’s situation across cultures and across time. As cultures change and adopt different values over time, cultures undergo phenomenological emergence. As a result, this genre also continues to grow alongside the contexts and cultures that it is present in. Although this genre seems to be only geared towards individuals with accessibility needs, the emergence of new UI design patterns build a strong foundation for the genre as a whole as it encounters new situations (Miller, 11). Research on these accessibility patterns in different contexts reveal how these components are not simply accommodations, but rather ways to create a more inclusive experience for everyone.

Advice

Currently, some see accessibility features as an accommodation but it can actually be used to create a more inclusive experience for everyone. What we need is “genre awareness”. In Genre: An Introduction to History, Theory, Research, and Pedagogy, Bawarshi and Reiff explain the importance of teaching with exploration. Students can gain awareness of the genre when they understand how it functions within different rhetorical situations and social contexts (Bawarshi and Reiff, 2016).

The genre of inclusive accessibility design is central to nearly every product or experience that designers in the UI/UX field create. Each product can be used by large audiences in a diverse range of contexts and cultures, so it is crucial that we as designers remember to account for the small population of people with visual impairment.

Vision for every point of view

The user’s transportation experience depends on the effectiveness of these features to guide the user through planning their trip, the platform experience, and the ride. Research can reveal how these components are not simply accommodations, but rather ways to create a more inclusive experience for everyone.

Citations

Bawarshi, Anis S., and Mary Jo Reiff. Genre: An Introduction to History, Theory, Research, and Pedagogy. Parlor Press, 2010.

“Deafness and Hearing Loss.” World Health Organization, World Health Organization, 1 Apr. 2021.

Miller, Carolyn R. “Genre Innovation: Evolution, Emergence, or Something Else?” The Journal of Media Innovations, vol. 3, no. 2, 7 Nov. 2016, pp. 4–19., https://doi.org/10.5617/jmi.v3i2.2432.

“The ADA and Public Transportation.” Legal Aid at Work, 10 Dec. 2018.