The fallacy of easy

On “ease-of-use” and accountability in design.

The first question I ask when meeting other designers is how they would define design. Some have asserted that there are no wrong answers to this question. They are wrong.

Here are three examples of what design is not:

- “Design is making something beautiful”

- “Design is making something easy to use.”

- “Design is making something beautiful and easy to use.”

Some of you may find this confusing. Because according to the wisdom of Twitter’s top design influencers, design is form and function — how it looks and how it works, right?

But..

Why?

Why have we defined beauty and ease of use as the non-negotiable North Stars of design? When was the last time we’ve stopped to ask ourselves, “does the product I am working on deserve to be beautiful? Does the feature my PM wants to ship deserve to be intuitive and easy to use?”

Sharing an article on Facebook is super easy — lighty tap the tip of the juicy share button to spray your followers’ News Feeds with some yummy content.

But does such an action deserve to be so easy?

By making Sharing a tap or two away, have we also diluted the gravity of that action? Sharing something in the real world in front of a group of people demands conviction and bravery; we share when we believe in what we have to say so much that we are willing to risk potential humiliation and ridicule. And as someone who was trained as an actor, I can tell you that it is never easy, no matter how it may look.

Just like how we hold Facebook’s content policies accountable for igniting the spread of misinformation, so too must we examine the paradigms and systems that afforded the spreading in the first place.

So, what if sharing was not so easy?

What if Facebook required everyone to open links before they share them?

What if users were only able to share one external link per day?

Limiting the amount/frequency of shares may add weight back to the action of Sharing, encourage users to be more thoughtful of what they share online, and improve the quality of content available on Facebook as a whole. It will add a sense of accountability to the action of sharing, and healthy communities cannot exist without accountability.

Yes, adding friction to the sharing experience would have a significant impact on Facebook’s bottom line — after all, unlimited one-click shares equal exponential exposure for advertising partners. But if Facebook really wants us to believe that its North Star lies in Connecting People, such sacrifices may be necessary.

Another example of something that was designed to make things “easy” is the infinite scroll invented by Aza Raskin. On paper, it sounds benign — and yet, the ease of use that the infinite scroll affords has been hijacked by designers at social media corporations to instead keep people in an endless machine state dedicated to consumption and ‘engagement’. What was originally intended to deliver power to people by reducing interstitial friction is instead being used to siphon agency and power away from people.

Maybe it’s time reintroduce friction in the browsing experience.

What if people were asked how much time they have to browse Instagram every time they launched the Application?

Even better, if this feature could talk to services like Lyft to generate a flow of content appropriate for the user’s context without burdening the user with setting expectations?

Instagram could then generate a curated flow of content with a hard stopping point, optimized to keep people engaged within their personally defined boundaries, politely stepping away once the user has achieved their intention.

Under this paradigm, users would become more aware of their relationship with technology and make necessary adjustments should they see fit. This could also act as a great intermediary step between two extremes (browsing infinitely vs. deleting your account).

You’re probably thinking about how no PM at Facebook would ever approve the hypothetical solutions outlined above. And who would blame them? Their performance and end of year bonuses are tied to quantifiable increases in click-rate. Plus, deliberate frictions in the experience will undoubtedly lose against solutions prioritizing ease of use when it comes to things like AB testing. Quantitive user research is often misinterpreted as “ruthlessly optimize for engagement” with little wiggle room for humanizing the experience. To quote a friend and fellow designer Davina Kim, “Why bother asking users how they feel about a design if ultimately you just ship what moves the needle?”

Just like empathy, great design cannot be quantified nor measured through engagement metrics. Great design is about empowering people to achieve their goals, not about manipulating people into doing what you want them to do. Being persuaded or manipulated into pressing a button is not the same thing as wanting to achieve something that requires pressing the button.

Design is political — a way of affecting human beings’ relationship with power. A way of controlling the flow of power through society. An opportunity to reinforce or dismantle through thoughtful invention.

It is also a form of colonialism; a select group of people making decisions on behalf of a larger population, often forcing those decisions because they are supposedly “better” or “more delightful” is — at its core — colonialist.

As designers, our job is more than just optimizing for visual elegance and/or ease of use. We must critically reflect on the role that we play in the world, to consider if what we are building is what the world needs, and to advocate on behalf of those who hold less power.

This might mean taking initiative and presenting a vision of a North Star we believe in. It might mean firmly pushing back on attempts to ship dark patterns. It might mean speaking up against an ordinance from higher ups that we perceive to be harmful to the world. It might mean making noise when capitalism prefers the comfort of silence. It might mean making space for the light of marginalized communities to shine through. And sometimes, it might mean walking away.

As long as designers continue to hold this power, designers also need to also be the ones held accountable for its misuse (intentional or not). Asking people why they don’t just delete their account points the finger at the user instead of the people who allowed for the exploitation to occur — especially when so many of our inventions were engineered to be as addictive as possible.

And as long as the world continues to adapt itself to the things we are making, designers will continue to shoulder the responsibility of power.

Whatever it is, it is not easy. But that doesn’t mean it should be.

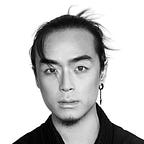

Jason Yuan

Human Interface Designer

Creator of Mercury OS