The one thing to make your (UX) research good

What you need to know when creating your own research design.

Research is complex and can be overwhelming. It’s very easy to lose your head and “forget” what it is that you are actually researching. Getting your participants to tell you what you want to know may seem impossible and it is incredibly hard to throw away your biases and keep your focus.

But there’s one thing that makes all the difference and prevents you from wasting time and other resources when doing research.

And it’s a well thought out research design.

Why bother with research design?

Simply put, research design is the plan. It’s the logical structure of any scientific work. It helps you stay on track and systematize the research so that you can get valid data and be confident when making decisions based on the results.

Because good preparation leads to good data.

And good data lead to good results.

The function of research design is to ensure effectiveness and objectivity of your work by providing a blueprint of sorts, for collection, measurement and analysis of the data.

There’s no universal guide to creating your research design because its content always depends on the type of study that is to be conducted.

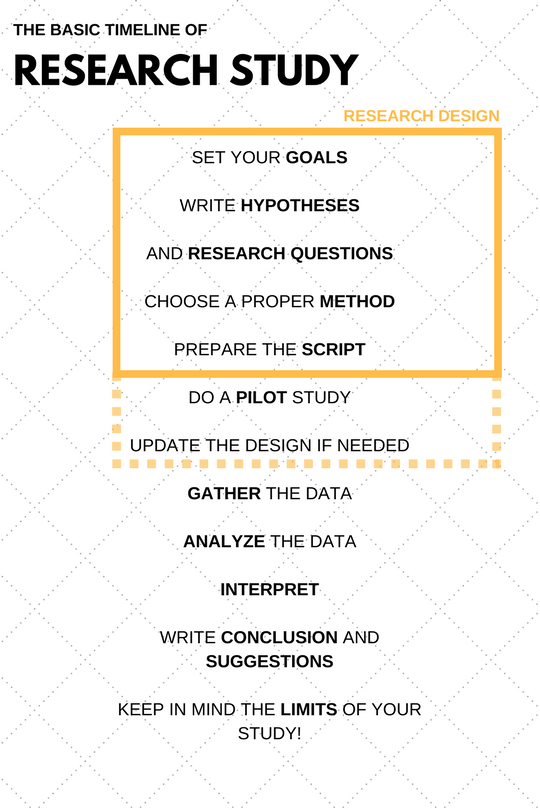

The image below shows a very general timeline and highlights the parts of the planning phase — the things you should consider when writing your own research design.

Research basics

AKA what you need to know when creating your own research design

Every research starts with stating the research problem.

This is the starting point that steers the direction of the whole design, from setting the goals to deciding on the method, gathering data and analysis.

It also helps you determine the type of the study:

- Quantitative (deductive)

- Theory → Hypothesis → Observation → Confirmation

- Qualitative (inductive)

- Observation → Pattern → Tentative hypothesis → Theory

Goals

Research goals give you the framework to work and think in. They stem from the research problem and are the reason WHY you are actually doing the research, tell you what is it that you want to achieve.

Example: The goal of this study is to see if watering flowers with sparkling water is more effective than watering with regular water.

The important thing about goal formulation (and hypotheses and research questions) is that it can help you to decide what methods to use. The words that you use when thinking about the goal of your study can act as a hint:

Hypotheses

Simply, hypothesis is an assumption in a testable form.

Hypotheses bring you closer to your goal by providing you with a testable statement that you should be trying to refute throughout your research.

- When writing your hypotheses, think about what’s the presumed outcome (result) of your research

- There can be one hypothesis, or more

- Good hypothesis is testable, you do not want to validate the hypothesis, you try to refute it

- Basically from now on, you are trying your best to prove that your hypothesis is wrong…

- … And when you fail to do so, you can say that your hypothesis was not disproved, therefore there is a high chance that it’s true

Example: Watering with sparkling water will lead to quicker growth in tulip flowers.

Note: there’s a thing used in statistics that’s called a null hypothesis (and you can read about it here).

Research questions

Once you have your hypotheses, you should break them down into logical parts, and ask your research questions:

- Written in form of specific, answerable and researchable questions

- Research questions are logically derived from hypotheses

- There can be multiple research questions for one hypothesis

- Research questions are all the questions you have to answer to be able to test your hypothesis

- It’s not a good practice to use research questions as interview questions for your participants (asking like this might lead to getting biased answers when participants know your goals, they tend to tell you what they think you want to hear)

Example: How much do the tulip flowers grow in a week when watered with sparkling water?

How much do the tulip flowers grow in a week when watered with regular water?

Sample

Selecting the right people for your research is the key to getting relevant information and therefore gathering valid data. You should think about exactly who are the people that matter to you in relation to your study, its topic and scope. And since you cannot take every person in your target population and study all of them, you have to make do with just a sample.

- Sample = set of units, that you are actually observing

- Population = set of units about which you want to make inferences

The size of the sample depends mostly on your chosen method, the availability and size of your target population and your research approach.

Qualitative studies are typical for just a few respondents, ranging from one person case studies to tens of people in experimental designs.

This again depends on the specific method you choose and also on the rarity of target population (if your population are bilingual people with Alzheimers that are under 25 years old, well.. then your population is presumably tiny and so will be your sample). Generally it is a good practice for in depth qualitative interviews to go with 5–7 people, although that, too, depends.

Quantitative studies are typical for bigger samples, again depending on the target population and the method used.

Quantitative data are usually analyzed with the help of statistics, which means that things like confidence levels and margins of error need to be taken in account. And that’s a whole other story.

Example of a research design

In Kentico — a company where I work as a UX researcher, we usually use research design for any upcoming study, including usability testing. It helps us stay focused and have a precise knowledge of what we are doing (instead of a vague idea of what it is that we are actually testing).

Here is a partial example of a simple testing design we used a couple of months ago.

Summary

Testing of an upgraded search/filter, that uses different patterns than what we previously used in our product.

Respondents

Anyone who works with content in Kentico Cloud (Kentico’s headless CMS).

Goals

Make sure people know how to use the new patterns to successfully filter content.

Hypothesis

H1: If we change the filters, then users will be able to filter content because the new pattern is understandable.

(note the “If__, then__ due to__.” formulation that helps you think about your hypotheses correctly)

Research questions

H1: Can specific filter be easily found within many others? (e.g. there’s a lot of content types and I’m looking for specific one)

H1: Is filtered inventory state easily distinguishable from the default (not filtered) state?

(note that navigating through the filter menu and understanding the filtering state were the identified concepts that would help us (not to) refute our hypothesis)

Creating a research design like this helped us create proper scenarios for testing and therefore ensure valid results.