Discovering the practice of design

From Sesame Street to Jared Spool — Embracing the Practice of Design.

When I was little, I didn’t know there was such a thing called Design. I knew I liked to draw, organize things and I felt happy when I saw Marimekko patterns or the typeface Bodoni Poster’s #5, but I thought that meant I was artistic.

When I think about it, I’m pretty sure I was drawn to design by Sesame Street, where letterforms and numbers were beautifully and creatively presented.

Most memorable to me is this film with Paul Benedict as a Mad Painter. He is a man determined to paint numbers on objects. Here, he deftly paints the number 7 on Stockard Channing’s red patent leather purse. (To this day, when I see a red patent leather surface, I want to paint a bold number 7 on it.)

In several short films, the Mad Painter embellishes quite a few purses, sandwiches and bald heads. In doing so, he showcases the beauty of numbers. At the same time, he was delightfully teaching kids how to recognize and draw numbers.

This is Design: a perfect demonstration of conveying information in an engaging way. To me, these films illustrate how design brings together empathy and an understanding of your audience. They delivered meaningful information, while encouraging the audience to learn more and at its most successful, create long-term impact.

Design is a powerful method of creative problem solving. It streamlines process, educates, facilitates conversations and brings beauty to our lives. While the tools of our daily practice are always changing, the essential elements of traditional design practice are still present. The process we use informs our work. It’s the way we dive into identifying and defining the problem and use research to generate solutions, test and iterate.

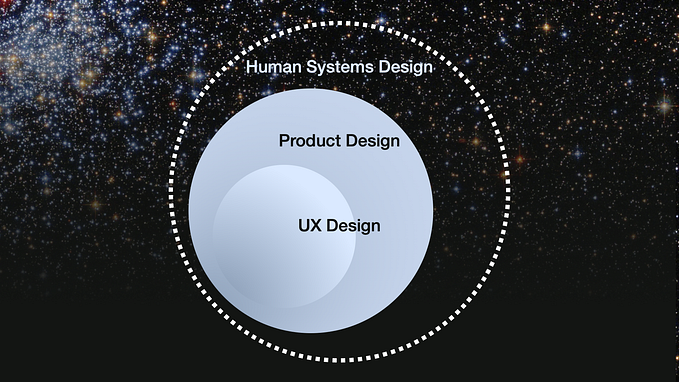

The experiences we help foster do not live in isolation. They are part of an ecosystem of an entire experience with a product or service.

Good design is not created by duplicating solutions found through a Google search (though recognizing effective design patterns is). We should be thoughtfully designing facilitating tools that fit within their ecosystems. Tools that connect people to information and to other people. To create such powerful tools, designers must understand their content and its surrounding context. We have to know about the audience, their environments, their activities and preferences. When we practice the design process, we can develop that understanding.

Along with the increased popularity of design and UX, we’ve seen the commoditization of the design process through Design Thinking. While its best intent is to share the successful methodologies to help teams practice and develop creative problem solving skills, it is not always implemented this way. Sometimes what’s missing, is an understanding of the true essentials of this process. Perhaps it is the influence of a society where the length of our attention span has become increasingly shorter and shorter. We can get anxious about the possibility of a perfect solution if we just enter a few keystrokes in our browser’s search bar. Hell, it saves time — and it could be a quick win that that one stakeholder or client will love.

The Practice of Design is also not simply time-boxed exercises using quirky metaphors to generate ideas on a whiteboard, in a vacuum (though these can be fun, don’t get me wrong). Nor is it creating solutions based on one’s own personal experience, or the ability to parrot quotes from Jared Spool.

- Michael Scott

To those in UX leadership roles who just shared Googled solutions to their designers, do you think that you are setting them up for success? Does it support their growth as a designer? What have you taught them? Instead, help give your teams a better understanding of the problems they are trying to solve. Take a moment to stop and think, ask questions, dive deeper. Empower them to think critically and be able to ask themselves the right questions by asking them the right questions. They will then develop the skills and language they need to articulate their rationale to stakeholders or clients. We want them to get to a point when they’re presenting solutions based on their systematic process, not on a lucky search result. Do you want their rationale to be, “Well, Beth told me to do it this way”?

Like the Mad Painter, we can make information engaging and impactful if we take the time to do it right. Commit to doing research and ensure that your team get the resources they need. You can help your teams deliver opportunities for meaningful experiences that engage, compel and make a long-lasting impact if you are not just focused on the moment. This is how we make our products better. It’s what makes this discipline so rewarding. I encourage designers to be true to our discipline and embrace the practice of design.

Additional Resources:

Swann, Cal. “Action Research and the Practice of Design” Design Issues, vol. 18, no. 1, 2002, pp. 49–61. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/i267312.

Malpass, Matt. Critical Design in Context. Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2019.

Monteiro, Mike. You’re My Favorite Client. A Book Apart, 2014.