This might be a terrible idea: why bad ideas are good for design

My UX team standing around a whiteboard full of drawings, staring in silence, is a common sight at our office. We have exhausted every idea we had and still feel like we are on the wrong side of complexity. We look over our busy whiteboards. I often sit back down and begin to ponder.

It is at these moments that one of my coworkers loves to say, “This might be a terrible idea,” then proceeds to draw something else. It usually is radically different from anything we’ve previously considered.

This “terrible idea” is often not the solution. Sometimes it is, but most times it is not. However, it almost always leads to the right solution. It jars the team out of our stupor and gets us back on track.

This has happened so much that it got me thinking about why these terrible ideas often lead to great things.

Authors understand this principle

If there is a group of people that know a thing or two about terrible ideas, it’s authors. As an aspiring novelist myself, I have put hundreds of terrible ideas to paper. Turns out I’m not the only one.

Anne Lamott in her book Bird By Bird talks about how getting these ideas out of her head are good for the writing process.

Almost all good writing begins with terrible first efforts. You need to start somewhere. Start by getting something — anything — down on paper. A friend of mine says that the first draft is the down draft — you just get it down. The second draft is the up draft — you fix it up. You try to say what you have to say more accurately. And the third draft is the dental draft, where you check every tooth, to see if it’s loose or cramped or decayed, or even, God help us, healthy.

- Anne Lamott

Stephen King has a rule that after he writes a first draft he must cut at least 10% while creating the second draft. He understands that his first draft is for getting all the ideas out and on paper. The second draft is for identifying which ideas have merit.

This same principle applies to UX work. Time and time again the correct solution does not present itself until after all the terrible ideas have been expunged.

Worst Possible Idea

Bryan Mattimore pioneered a creativity exercise called “Worst Possible Idea.” The premise behind this idea is that you gather together with a problem in hand, except the only guidance the group is given is that they have to think of the worst possible idea to solve the problem.

What they have found is that getting a group of people to stop trying to find the best possible answer and instead try to find the worst possible answer is that it frees people up mentally. Where before they were hesitant that their idea would not be the ideal solution, they are now relaxed enough to suggest whatever idea they want.

We attempted this in one of our design sessions. I remember one of my coworkers drawing a picture of a search bar that zips around the screen, avoiding the user’s ability to even click on it.

We all had a laugh imagining a search bar roaming around, evading the users mouse. But it brought a solid principle to our minds: put things in a place where users can click on them.

Below is an image of a recent whiteboarding session. Most of the ideas on the whiteboard did not make it into the final product. And yes, in the bottom right is an image of Abraham Lincoln vomiting content onto the screen, a terrible idea. But those terrible ideas led to great ideas that did make it into the product.

Why do bad ideas lead to good ones?

As a society we value the right solution, getting there quickly, and acting on it. We’ve been taught ever since we were children that we needed to find the right answer and show your work, yet, when we demonstrate our work we usually only show the things that led to the right solution — the part after all the bad ideas.

There are many reasons why we, as a society, abandon creative thinking as we enter adulthood. For one, creativity is messy and uncertain; it goes against everything we learn along the way in formal education and through socialization.

- Yazin Akkawi “Why Bad Ideas Are The Key To Being More Creative”

Creativity is messy, and sometimes people don’t like to get messy. Well, in design you have to get messy.

Akkawi goes on to give two reasons why bad ides are not just good but necessary.

There are two reasons why embracing bad ideas is necessary for great ones:

1. Ideas that solve a problem in a unique way are usually a combination of existing ideas, many of which may seem bad at first.

2. Accepting that most of your ideas will be bad will help you move on to new ideas faster and more easily.

Ultimately, like most things, creative thought is a trial-and-error process that requires failure. And while bad ideas can be building blocks to creative thought, sometimes they are in fact actually good ideas — just ones that nobody else understands yet.

Bad ideas provide valuable insight

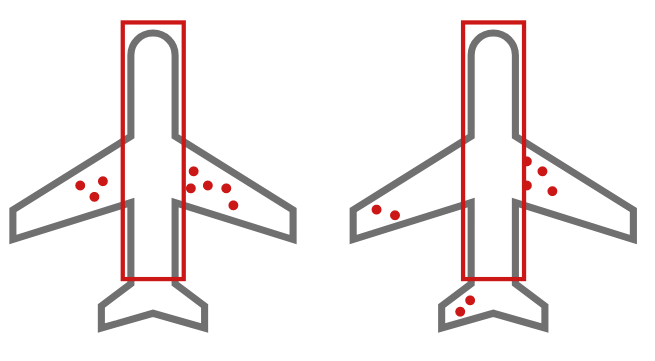

During World War II, the statistician Abraham Wald was asked to figure out a way to minimize bomber losses to enemy fire. Researchers at the Center for Naval Analyses had attempted to solve this problem by analyzing where returning planes took the most damage. They came up with the solution that if planes are getting shot more on a certain part of the aircraft that they could reinforce those areas with extra armor.

Makes sense, right? Planes get shot more here than other places, so let’s protect those areas. Wald noticed an error in their thinking, however. He proposed that they armor the places where the returning ships did not take any damage, his reason being that the aircraft that returned demonstrate everywhere that a plane could be shot and still return home safely. The areas that needed more armor were the places that damaged a plane so badly that it did not return. Those planes were lost in crashes, so studying them proved problematic, but they used the returned places to identify what areas hadn’t been shot and they armored those areas.

This thinking is often referred to as survivorship bias. We study what led to the right solution but often skip all the mistakes made along the way. We need to make mistakes, we need to study the mistakes, we need to learn from the mistakes.

If designer and researchers do not sometimes fail, it is a sign that they are not trying hard enough — they are not thinking the great creative thoughts that will provide breakthroughs in how we do things. It is possible to avoid failure, to always be safe. But that is also the route to a dull, uninteresting life.

- Don Norman “The Design of Everyday Things”

Conclusion

As UX designers — and society in general — we need to stop avoiding mistakes and start embracing them as steps towards our goal. In my career, I have seen this principle play out time and time again. The first wireframe on the whiteboard is almost never the right idea. If you only ever explore one option, you will miss out on the truly innovative solutions that might take your designs to the next level.

We need to remove the word failure from our vocabulary, replacing it instead with learning experience. To fail is to learn: we learn more from our failures than from our successes. With success, sure, we are pleased, but we often have no idea why we succeeded. With failure, it is often possible to figure out why, to ensure that is will never happen again.

- Don Norman “The Design of Everyday Things”

The next time you are in a design session and you think, “this is a probably a dumb idea, I won’t share it” remember, that terrible idea might be the first step toward the right idea. You never know, the right idea might be just around the corner, so let those bad ideas fly.