Using systems thinking as a design leader

How to guide organisations towards innovation with a more interconnected, dynamic approach to design.

Systems are everywhere, from websites and businesses to entire cities and economies. They consist of many interconnected parts working together to achieve a goal, like how immune cells team up to protect the body against infections.

Viewing the world through a systems lens helps us look beyond isolated parts to see everything as a whole. This mindset shift is vital for innovating products, services, and any initiative to enhance a process, community or economy. Welcome to systems thinking.

Thinking in Systems

Systems thinking is an approach explored by the late Donella H. Meadows in her book Thinking in Systems: A Primer. It teaches us to understand system parts, structure, and behaviour to design for a more sustainable and efficient world.

“A system is a set of things — people, cells, molecules, or whatever — interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behaviour over time.” — Donella H. Meadows.

As a UX practitioner, I’ve worked with many small and complex systems — from products, services, and spaces to events. However, systems thinking doesn’t stop when the project ends — it applies to everyday life, too. Everything from ordering a coffee in a hipster store to managing your money in a banking app involves an interconnected web of working parts.

Here’s a true story. On a recent vacation in sunny Dorset, I had a firsthand experience of how things interconnect. After returning from a family day at the beach, I realised I’d lost my wedding ring. While I was panicking, my wife casually checked a local Facebook lost property page and miraculously found a post with a picture of my ring! After several messages, we arranged to pick up the ring at a coffee shop the following day.

Many would credit Facebook, but I see it as the power of a well-functioning system that creates positive outcomes (like rescuing my marriage).

In this story, we’ll discuss how adopting systems thinking can help solve complex problems and drive innovation. Here’s a quick overview to glance:

- 🧠 The dynamic nature of systems thinking.

- ⚙️ Systems thinking core concepts.

- 🔬 Applying systems thinking to real case studies.

- 🪲 Addressing root causes of system problems.

- 🎯 Enhancing systems with leverage points.

I can’t guarantee systems thinking will solve your love life (or rescue your marriage). Still, it will provide a different way of looking at the world. First, let’s revisit Donella H. Meadows’ classic, Thinking in Systems: A Primer.

Thinking in Terms of a Dynamic World

We often get caught up in surface-level details, missing the bigger picture. However, Thinking in Systems: A Primer teaches us to shift from a static worldview to a dynamic one.

“You’ll be thinking not in terms of a static world, but a dynamic one. You’ll stop looking for who’s to blame; instead, you’ll start asking, what’s the system?” — Donella H. Meadows.

As Meadows explains, a system is more than the sum of its parts. It’s about how those parts interact to produce behaviours over time. For example, a car has various components like the engine and wheels. Still, they must work together to achieve the goal of transportation. If one part fails, the whole system is affected.

For instance, I once faced an annoying struggle when trying to lock my car. Usually, the indicators (turn signals) blink, and the wing mirrors automatically fold in upon pressing the lock button on the remote. After much confusion, I realised I’d left the rear door slightly ajar by a slither! I could have avoided this trap if the car had provided better feedback.

“Systems Thinking is a way of thinking that gives us the freedom to identify root causes of problems and see new opportunities.” — Donella H. Meadows.

A car that fails to lock is relatively minor compared to more complex, dynamic systems like a hospital emergency department. Doctors, nurses, and other vital medical staff work together within challenging conditions to provide timely, effective patient care. Errors in the system can lead to incorrect diagnoses and treatment delays.

When thinking in terms of a dynamic world, we look beyond the isolated issues and quick fixes. This broader perspective enables us to address underlying patterns and improve outcomes across entire systems. Before delving into the core concepts of systems thinking, let’s explore its origins and development and reveal why it is essential for innovation.

The Origins and Development of Systems Thinking

We can trace the origins of systems thinking back to the 1930s when biologist Ludwig von Bertalanffy developed general systems theory. In the 1950s, Jay Forrester at MIT advanced the approach with system dynamics. The work eventually led Meadows to apply it to global issues, especially sustainability.

Meadows’ work on systems thinking spanned from the 1970s through the 1990s, leading to the publication of Thinking in Systems: A Primer in 2008. Her ideas continue to shape fields such as sustainability, organisational behaviour, and, notably, product and service design.

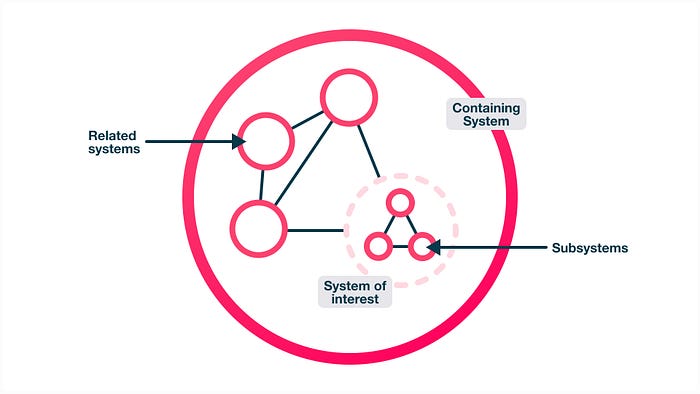

Regardless of the field’s evolution, systems thinking revolves around the idea that every system exists within a larger, interconnected framework. The “Poached Egg” diagram in Figure 1 is one example that captures this concept, illustrating the organisation and hierarchy of systems.

So, what about systems thinking in product and service design? An article by The Systems Thinker explores the potential of combining systems thinking with other methodologies, like design thinking. By adopting a systems “worldview,” various disciplines, such as designers, researchers, engineers, and stakeholders, can collaborate more effectively to develop sustainable and impactful solutions while considering complex, interconnected systems.

“We have shown that systems thinking can help designers better understand the world around them.” — The Systems Thinker.

The article further suggests that systems principles guide teams to enhance an entire system’s performance, even when focusing on one part. By considering unintended consequences, teams can expand their approach to product and service design, refine processes, and drive innovation with a holistic perspective.

We’ll later learn more about how we can apply systems thinking to product and service innovation, but first, let’s look at its core concepts.

The Core Concepts of Systems Thinking

Meadows’ core concepts, including stocks and flows, feedback loops, delays, and resilience, help us understand how complex systems function and adapt. Let’s take a look.

Stocks and flows

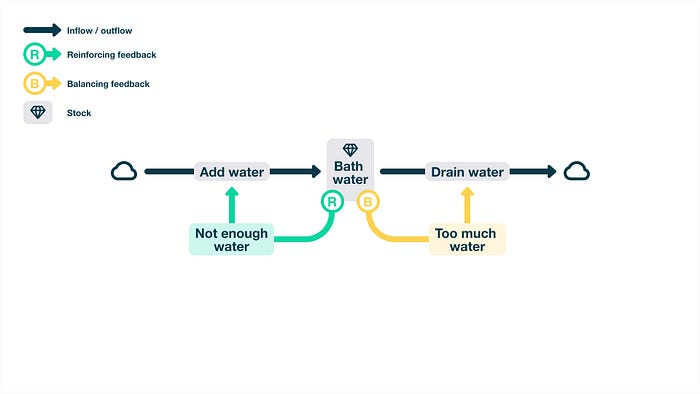

Stocks and flows are fundamental concepts in both simple and complex systems. A stock refers to the reserve accumulating material or information, while the flows are movements that alter these stocks. For instance, consider filling a bathtub: when you turn on the tap (the flow), the water level (the stock) increases.

We can also maintain a system’s stock by regulating inflows and outflows. For example, you would balance your bank account by managing your income and spending.

Feedback Loops

Feedback loops are crucial in regulating systems by sending signals that manage stocks and flows. A balancing feedback loop helps maintain stability, like draining water from a bathtub. In contrast, a reinforcing feedback loop amplifies change, like adding more water to increase the water and multiply those lovely bubbles.

Figure 2 illustrates how Meadows organises stocks, flows, and feedback loops within an interconnected system. The systems diagram represents stocks as boxes, while arrow-headed pipes signify flows and feedback loops. Furthermore, to help focus on the present discussion, the use of clouds stands for external factors or other system areas.

Delays

Delays occur when systems take time to react, like a car dealer waiting for a manufacturer to adjust its production in response to increased customer demand. Feedback delays can also reduce system reaction times, making issues harder to address, often leading to missed opportunities or dire consequences.

For example, in a kitchen, every role — from the chef to the pot washer –plays a crucial role in running a smooth functioning system. Everyone must work together to guarantee fresh ingredients, clean pots, and prepared dishes are ready when needed. Even a workstation not being cleaned on time can disrupt the flow, causing food orders to back up. The result? Frustrated customers left waiting for their meals.

Resilience

Resilience is a system’s ability to absorb shocks and maintain functionality, such as a diverse forest ecosystem or a business adapting to environmental changes. Systems also achieve stability through stocks, which act as buffers for delays.

For example, in the Trading 212 app, users can create diverse investment portfolios known as ‘pies.’ Each pie consists of ‘slices,’ representing market stocks and ETFs. Users lower their risk by spreading investments across various slices and making their portfolios more stable. This setup helps protect against significant losses, making the investment system more resilient to market changes.

These concepts offer powerful principles for understanding and working with the complex, dynamic systems around us. Next, we’ll put these into practice using three case studies.

Systems Thinking in Practice

The case studies below demonstrate how systems thinking can drive innovation in real-world products and services. First, we’ll look at how a UK bed retailer combines technology with customer care within a dynamic system, showing how these principles can enhance customer experiences and business resilience.

Case Study 1: Dreams’ Sleepmatch Technology

The Sleepmatch experience at Dreams, a UK bed retailer, shows how systems thinking can help innovate the in-store customer experience. Recently, I underwent the system firsthand.

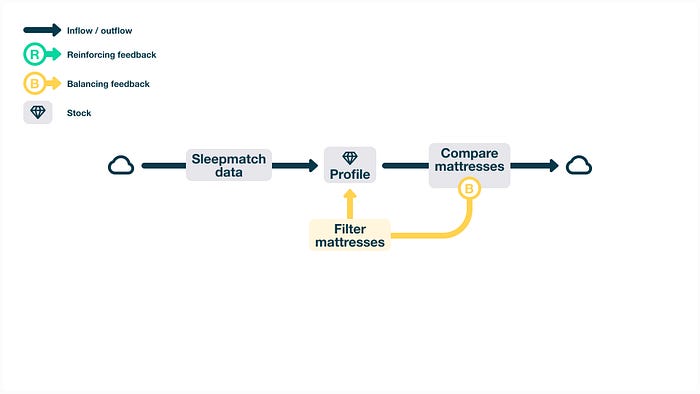

During my visit, a Bed Expert (yes, that’s a thing) had me lie on a unique Sleepmatch bed to map my body and sleeping position. They used the flow of information to recommend mattresses that best support my sleeping habits. In this case, the stock included profile data on my needs with matching mattress recommendations.

Next, the Bed Expert carefully observed my behaviours when trying the different mattresses. Using my reactions as a feedback loop, they helped me narrow down my options to an eventual winner.

That day, I left the store as a satisfied customer due to a well-functioning system. The timely and accurate data helped reduce delays, leading to faster decision-making for myself and the Bed Expert. Furthermore, an efficient, interconnected system is a resilient system that can adapt to changing customer needs.

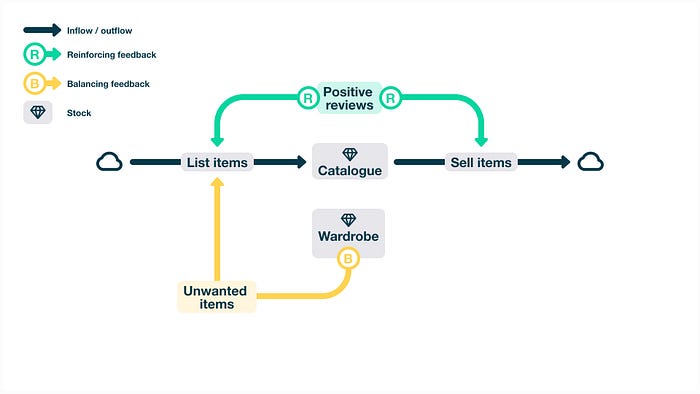

Case Study 2: Vinted’s Circular Fashion

Vinted, an online marketplace for buying and selling goods, plays a significant role in the circular fashion economy. People worldwide can recycle their wardrobes by selling unwanted clothes (and other items) to others looking to replenish theirs.

When we view Vinted through a systems lens, we can see how its interconnected parts, including sellers, buyers, items, and transactions, work together to achieve sustainability. In this case study, we’ll focus on a specific part of the system: selling and offloading unwanted items.

We can identify two stocks within Vinted’s system. The first is a catalogue managed by platform members, which includes the inflow of used items and an outflow of sold items. The second type refers to an individual’s wardrobe containing purchased and unwanted items. The exchange of items between sellers and buyers ultimately supports the circular economy by keeping resources in use.

Next, feedback loops in the system help reinforce sustainable behaviours. Positive reviews, for example, motivate sellers to list more used items, while trusted sellers attract more buyers. This loop grows the platform’s user base and expands its impact on the circular economy.

Regarding delays, Vinted provides regular order updates for buyers and sellers to help manage expectations, improve response times for timely deliveries, and enhance the overall experience. Additionally, clear communication coupled with eco-friendly practices helps Vinted build its resilience and thrive in a circular fashion culture.

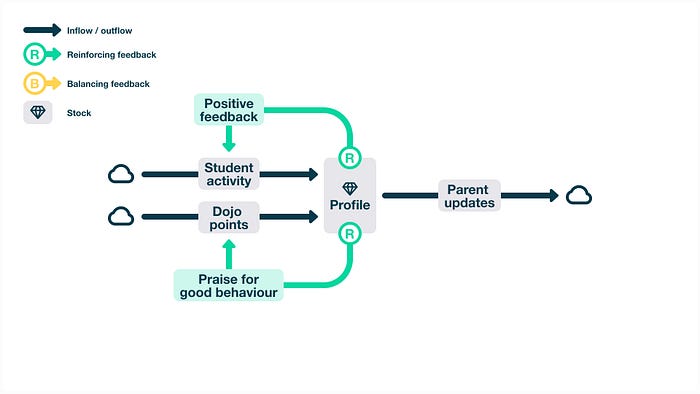

Case Study 3: ClassDojo’s Education Community

ClassDojo is an educational platform that connects teachers, students, and parents as a community. It plays an essential role in my family’s life, where my wife and I keep track of our children’s progress and solve many mysteries, such as missing school jumpers and half-chewed homework.

The platform’s stock refers to the student’s profile managed by their teacher, which includes the inflow of activity updates and an outflow of parent notifications. Additionally, teachers can reward good student behaviour by adding Dojo Points to their profile.

Feedback loops include parent comments and praise for their children’s efforts and behaviour. Positive feedback encourages students to keep up their performances, reinforcing the cycle.

To help reduce delays, teachers can swiftly inform parents of urgent updates and cancellations for upcoming events. Likewise, parents can message teachers about concerns regarding their children, such as illnesses or mysteriously missing sports kits.

The resilience of ClassDojo lies in its ability to adapt to the needs of its users. Parents can track student progress, teachers can share resources, and students can earn rewards. Overall, ClassDojo’s dynamic system helps a school community to cultivate an innovative, responsive, and supportive learning environment.

Case study takeaways

The case studies help us understand how to apply systems thinking to products and services across different industries. The principles provide viewpoints on how brands and communities solve problems and achieve outcomes. Here’s a quick summary of what we learned:

- Feedback loops drive engagement: Whether through Vinted’s user reviews or ClassDojo’s Dojo Points, feedback loops assist decision-making and encourage continued engagement.

- Delays need targeted solutions: Addressing system delays improves efficiency. Dreams’ SleepMatch, for example, quickly generates insights to streamline the trying and buying process.

- Resilience aids sustainability: Systems like Vinted and ClassDojo thrive on resilience, ensuring they adapt to changes and continue to provide value.

Understanding the core concepts of systems thinking helps us recognise how effective and resilient systems function. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that systems can also fail due to underlying issues. In the next section, we’ll explore Meadows’s insights on this area.

Addressing Root Causes of System Problems

When we ignore or fail to recognise underlying problems, we fall into what Meadows refers to as traps. For example, using quick fixes, like temporary solutions that only address surface issues, can create a slippery slope where the root cause of the problem worsens.

In 2003, Lego was months away from bankruptcy due to losing its focus by diversifying into non-core areas such as jewellery, clothing, and theme parks. Its misalignment with its original strength — the power of storytelling through the humble brick — ultimately led to a downward cycle.

Fortunately, Lego went beyond surviving to thriving as a multi-billion dollar brand. They identified the traps and recognised the need to focus on the storytelling aspect of the brick. They reduced complexity and integrated other industries, like digital, into their ecosystem.

We’ll learn that many traps can arise in products and services, hindering innovation and organisational performance. Meadows identifies eight patterns and explains how we can avoid them and even turn them into opportunities. In no particular order, let’s take a look at each one:

1. Policy Resistance

- The trap: Stakeholders pull in different directions, which results in project delays, misaligned goals, and waste.

- Opportunity: Encourage early collaboration to align goals and streamline the innovation process.

2. The Tragedy of the Commons

- The trap: Teams overuse shared resources like budgets and personnel, leaving insufficient funds and skills for others.

- Opportunity: Set up sustainable practices and feedback loops to balance resource use and promote fairness.

3. Drift to Low Performance

- The trap: An organisation enters a downward cycle by accepting lower standards due to past setbacks or limited success. Like the Lego story, this behaviour reduces alignment with the group’s strengths and values.

- Opportunity: Establish and reward higher benchmarks to encourage consistent progress and innovation. Also, rediscover the original value offerings that made the product or service successful.

4. Escalation

- The trap: Competing teams or companies compromise quality in a race to innovate faster, leading to diminishing outcomes. This particular behaviour emerges when teams prioritise delivering new product features at speed.

- Opportunity: Encourage a balanced approach focusing on quality outcomes, sustainable growth, multifaceted value, and shared advancements.

5. Success to the Successful

- The trap: Here, the rich become wealthier. However, in the case of innovation, one high-performing team may receive the most resources, leaving others with fewer opportunities to innovate.

- Opportunity: Distribute resources and recognition more evenly, empowering all teams to contribute fresh ideas.

6. Shifting the Burden

- The trap: Relying on short-term fixes, like outsourcing design and development, can create dependency and slow down innovation.

- Opportunity: Focus on developing in-house capabilities for sustained, long-term innovation and expertise.

7. Rule Beating

- The trap: Strict rules and regulations, ranging from organisational frameworks and values to compliance and legal policies, hinder opportunities for growth and innovation.

- Opportunity: Introduce flexible guidelines around frameworks and policies that allow teams to find compromises based on their needs. This approach can result in more significant innovation and autonomy.

8. Seeking the Wrong Goal

- The trap: Focusing solely on short-term metrics, such as quarterly profits, can obscure meaningful outcomes, like customer value.

- Opportunity: Embrace long-term objectives and focus on multifaceted value to foster sustainable innovation.

Addressing common traps, such as misaligned goals, resource overuse, and narrow focus, can help us foster a more balanced and sustainable approach to innovation. Next, we’ll examine where leverage points in the system can lead to significant impacts.

Enhancing Systems with Leverage Points

We can enhance a system’s behaviour, efficiency, and sustainability by making specific adjustments, which Meadows refers to as leverage points. For example, by combining customer insights with design and engineering expertise, a team can determine the areas within a product to focus on to achieve better outcomes.

“Leverage points… are places in the system where a small change can lead to a large shift in behaviour. Leverage points are points of power.” — Donella H. Meadows.

Leverage points enable strategic optimisation and innovation without significantly changing a product, service, or entire system. For example, in 2020, IKEA launched a Buy Back & Resell program, which rewards customers with in-store credit for returning unwanted furniture. This scheme shows how the Swedish brand slightly adjusted its system to encourage eco-friendly behaviours.

Meadows identifies twelve leverage points, ranging from specific concepts like stocks and flows to overarching beliefs. We’ll examine each point with examples related to innovation, culminating in the most effective and impactful one.

Numbers

- Leverage point: Modifying parameters and adjusting numbers can affect the system, but not always in full.

- Example: A subscription platform increases its free trial period to boost sign-ups; however, the change doesn’t guarantee long-term engagement or retention.

Buffers

- Leverage point: Increasing stock reserves relative to system flows can prepare the system for sudden or unexpected changes but may reduce flexibility.

- Example: A sustainable clothing brand boosts its stock of recycled fabrics to meet high demand; however, this change limits flexibility to adapt to new design trends.

Stock and Flow Structures

- Leverage point: Physical changes can affect a system’s overall performance, but these transformations are often slow and costly.

- Example: A healthcare service introduces wearables to enhance diagnostics and patient treatment; However, doing so requires time and resources, including funding and staff training.

Delays

- Leverage point: Reducing feedback delays can improve a system’s response time and ability to adapt to changes.

- Example: A SaaS company uses customer feedback to quickly address issues, maintain high standards, and reduce churn.

Balancing Feedback Loops

- Leverage point: Balancing feedback loops can help control a system’s stock and stability.

- Example: A smart home thermostat maintains the room temperature to a constant desired level.

Reinforcing Feedback Loops

- Leverage point: Reinforcing feedback loops can help drive a system’s growth but may lead to decline and collapse.

- Example: A retailer rewards customer loyalty with exclusive promotions to encourage repeated purchases of targeted items.

Information Flows

- Leverage point: Adding or restoring information, including timely, accurate data, makes the system more efficient and resilient.

- Example: An indoor smart meter reader offers homeowners insights into their energy consumption. Doing so allows them to modify their behaviours, such as adjusting heating and appliance usage, to enhance efficiency and reduce costs.

Rules

- Leverage point: Rules can influence or reshape the desired behaviour across a system.

- Example: An online marketplace for short and long-term homestays changes its policies around guest verification and review standards to promote trust, accountability, safety and positive interactions on its platform.

Self-Organisation

- Leverage point: Systems can evolve using any of the above leverage points to help increase adaptability and resilience.

- Example: A music platform uses AI to adapt to user listening habits and trends, thus providing a more meaningful and responsive experience.

Goals

- Leverage point: Aligning a system’s goals with a greater purpose can help reshape efforts, fostering meaningful and lasting change.

- Example: A software company prioritises features focusing on customer value rather than profit alone.

Paradigms

- Leverage point: Changing core beliefs can help transform a system’s structure and behaviour.

- Example: A retail brand moves from a throwaway culture to a sustainable one by encouraging customers to reuse, recycle, and upcycle used products.

Transcending Paradigms

- Leverage point: Letting go of fixed mindsets can increase a system’s flexibility and openness to innovative approaches.

- Example: A movie rental service transitions from rigid postal DVDs to flexible, on-demand digital content, resulting in transformed entertainment.

Leverage points enable us to drive innovation in our products, services, and systems through incremental, targeted changes. Brands like Amazon and Netflix have transcended traditional paradigms, redefining how customers engage with and consume their products and content, setting new industry standards. Ultimately, a resilient, efficient, and effective system can seize opportunities for adaptation and transformation.

Conclusion

Systems thinking is a holistic approach to connecting all the parts in something expansive, from products and services to cities and economies. It shifts our focus from the surface detail to the interconnected components that shape the bigger picture.

Meadows emphasises that systems thinking enables us to identify root causes, foresee unintended consequences, and pursue opportunities that create lasting change. Rather than address individual problems in isolation, we can interconnect to address the broader system. Whether scientists worldwide collaborate to overcome challenges or a community comes together to reunite a lost wedding ring with its forgetful owner, systems thinking is a powerful mindset that benefits everyone.

Ultimately, Meadows’ wisdom and legacy encourage us to engage with the systems around us, fostering a mindset that can revolutionise design and drive impactful, enduring innovation.