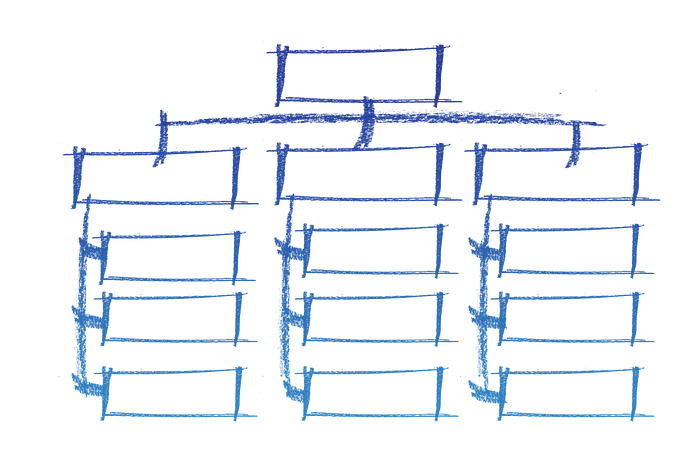

The org chart as a UX challenge

Sometimes the problem is the result of structure of the organization

As a user experience designer it is tempting to imagine that every user experience problem can be addressed through design. But sometimes the root cause of a problem is a little above our pay grade. Sometimes the problem is the result of the structure of the organization.

Back when I was a wee lad, marketing and product were distinct departments at most companies. This made sense. The product group focused on the development, improvement, manufacturing and distribution of products. Marketing was happy to convince customers they needed those products. Everyone stayed in their boxes and everyone was reasonably happy.

Then one day, along came the internet. Marketing departments reluctantly came to realize that most of their marketing activities would move online — display, search, and crm driving customers to “the dotcom” filled with information to drive conversion. At the same time, product managers reluctantly came to realize that much of the product experience would move online — proprietary platforms and services were abandoned in favor of an open standard available to all through the browser. To the customer or user, the journey from the land of marketing to the land of product — a journey that used to involve trips to a store or calls from a salesperson — was reduced to a single click.

There’s a funny thing about roles and responsibilities; once you put them in place they’re fiendishly difficult to change or evolve. Despite the fact that intelligent and customer-focused individuals in both product and marketing understand that the distinctions between their responsibilities are being eliminated, no one is willing to give up control over their part of the customer experience. Across the enterprise today, territory is being staked, marked, and vigorously defended.

There is a civil war inside the modern enterprise and the effects of it are painfully obvious to users. At the key moment — the “click” that turns prospects into customers — the digital experience becomes unrecognizable. Designs change. Navigations change. Color schemes, layout, buttons vs. pulldowns, information architectures and methodologies — everything changes. At the exact moment where we begin our relationship with our customer, we change all the rules. This is very, very, very bad UX. (Very.)

We all know this is a problem. If you sit down with twenty different product managers and twenty different marketing managers, they will all agree that user experience should be consistent across all digital touchpoints. Oddly, they will also agree on the solution — “those other folks should follow my lead.” To the product people, it is obvious that the product is the heart of the digital experience and marketing should prepare users for that experience. To marketers, their digital efforts are the introduction to the company and the product group should continue in the vein they started. Marketers believe they understand the voice and the mindset of the customer. This external focus makes them the natural guardians of user experience. Product managers will insist that their focus is making the product as useful and sticky as possible. Their knowledge of how customers use the product make them the natural owners of UX.

The Solution: Play Nice

Depending on the nature of your company and your role, there are different ways to begin to bridge the marketing/product divide in user experience. Unfortunately, overcoming this type of structural problem is never easy.

If you are an external vendor, you are in an unenviable position. If you were brought in by marketing, the product managers consider you (at best) a smooth-talking moron without the authority or experience developing a product. If you were brought in by product, the marketing managers consider you (at best) a technically-adept nerd who lacks the vision and strategic focus to talk to prospects. The only hope you have to break out of this impasse is to move upwards within the organization. Find someone with the authority to tell both marketing and product to play nice together and convince them that you can serve as an honest broker serving the needs of both sides.

The solution can never be that one side wins over the other. Whether you are a vendor or serve as the internal UX director, you must remember that a positive and consistent user experience between product and marketing can only be achieved by balancing priorities. If the marketing UX prevails, it will not be completely right for the product because it wasn’t developed with the product in mind. The product user experience, while appropriate for people who are already customers, is rarely accommodating of the learning curve for prospects. Creating a user experience that can be shared by product and marketing is a delicate task.

It is natural to imagine that this balance can be achieved by organizing a group of stakeholders representing both product and marketing and bring them together to develop the user experience in a series of internal meetings. While well-intentioned, this approach won’t work. Both sides have a vested interest in the failure of this effort. After all, if you fail to create a shared user experience, they can just go back to controlling their own part of the customer journey without integrating any of the hated compromises.

Since the problem is tribal and territorial thinking, I believe the solution is tribal and territorial thinking. I have been impressed by the approach of consulting companies like Accenture and BCG Digital Ventures. These companies take a group of people from different departments within their client companies and pull them to an offsite location for weeks or even months at a time to develop digital initiatives. Because these individuals are literally removed from their comfort zones, they slowly begin to develop a new sense of themselves as a cohesive team. This leads naturally to team-first priorities that are less influenced by naysayers within their old departments. Individuals from the offsite team eventually return to the office as champions for the initiative they helped to develop. I believe that such an approach is probably the best solution to the product/marketing divide in user experience. Combining mid- to senior-level people from different departments and assigning them the task of setting user experience guidelines for all digital properties will require a significant time investment and executive-level sponsorship.

Of course if you are only a humble UX designer, significant time investments and executive-level sponsorships are just two of the many things you don’t have access to. Don’t despair. There’s another way, although it is a slower, bumpier road. You need to look for the small wins. This requires that you and the other members of your UX team have a strong sense for what you think the eventual user experience guidelines should be. Then, you need to make yourself useful. If marketing needs a quick microsite, offer to help with the UX and apply your (secret, hidden) guidelines. If product adds a new module, offer to help again and, again apply your guidelines. Don’t be too literal in how you apply your guidelines. Always be flexible to the needs of the project. Over time, these small projects will teach you about the differing needs of product and marketing and how to balance them to create a single user experience. By the time you’ve gained the trust of both departments, your guidelines will have evolved significantly and been tested and proven in application. Eventually, you’ll need to create a deck and get buy-in across the organization, but hopefully by then you will preaching to the choir.

None of this is easy. It requires a completely different set of skills than the narrower toolset of user experience today. But, if UX is ever going to become a center of excellence within your organization, you cannot afford to shrug your shoulders about structural problems and departmental silos. Remember: you’re here for the users and the users deserve better.