UX, now what? Why your report needs impact and how to achieve it

Why UX research can suffer from the ‘now what?’ effect.

If we’re not careful, our reports contain too much data and not enough consequence. We often don’t spend enough time helping with understanding, mindset and next steps, and because of this even some of the worlds largest organisations can be left dubious as to UX’s importance in decision-making (see Uber’s 2019 firing of UX staff).

Over dinner, once, while travelling on fieldwork, a CEO asked me “How will you stop this report from gathering dust on a shelf somewhere?”. It’s a surprisingly common question, and I don’t remember my answer. I probably fumbled it, but I blame the wine…

Well, 5 years on, I’ve had time to think, test, and fail a few times, and here is what I’ve learnt:

As researchers, we are prone to spending too much time on academically rigorous analysis, delivering unbiased observations and asking more questions — believing that product teams will read, cross-check, interpret and run design workshops around every insight.

As researchers, we are prone to spending too much time on academically rigorous analysis, delivering unbiased observations and asking more questions — believing that product teams will read, cross-check, interpret and run design workshops around every insight.

In reality, this just doesn’t happen. At least, not for every insight, every point, or every feature. For product teams and senior sponsors who have to relentlessly prioritise, time is short and reports can be skim-read.

So, what can we do to help?

Well, I should caveat this post by stating that in an ideal world, a report should only ever be a reminder of an experience, of that time when the reader saw their users first-hand, of a workshop they attended to dig into learnings, of that conversation they had when they realised they need to re-think one of their assumptions. There is a place for a lengthy report, particularly in on-boarding and in documenting specific topics, but if you’ve done it right, the reader of your report should already know most of it before they read it.

With that in mind, here are my tips on how to create a report for impact.

#1. Consider the audience

Most of your readers will be looking for something specific, to prove or disprove a theory, or to help prioritise next steps.

But this is often not the same for everyone. It is important, therefore, to know:

- Who will read the report,

- Where the research sits within the wider business processes,

- How experienced the readers will be in interpreting the messages contained within,

- How enthusiastic or sceptical they are likely to be.

This information will help you tell your stories in a way that will engage well and maximise impact.

Katya Hott wrote a thought-provoking piece exploring how to tailor reports to two audience-based factors: The organisation’s trust in research, and it’s maturity as a research practice. Its well worth a read.

In my experience, there are two ways to get this information — explicitly and implicitly.

Explicit (Ask directly)

A good starting point for any research project is to run Stakeholder Interviews with a wide selection of people who will be directly or indirectly impacted by your outputs. There are many good resources on how to run these, so I wont go into that now.

However, its important to note that the power of a stakeholder interview doesn’t just lie in the insights you can gain; It goes the other way too. It is a chance for your stakeholders to learn about the project and start to engage with it’s potential for impact.

A happy, engaged former sceptic can be a powerful ally in engaging the wider business. So make sure you don’t outsource these interviews to another team, and make sure you turn them into a two-way discussion, not a one-way interview. Give as much as you take.

Implicit (Work closely)

While interviews are useful, you may not have the time or budget to run them before every piece of research.

A more time-efficient and powerful way to understand your stakeholders is to invite them into your world. Invite them to help write your scripts, to workshop with you, to join you in the back room in UX labs and to help with analysis (e.g. in a ‘War Room’). They may not initially expect this, or have time, but push them as hard as you can to join you.

Spending time with them, learning their unique place (and pressures) within the business, throwing solutions around (even if they are bad ideas); This is the best way to understand your audience, and understand what stories would be compelling, new and important to tell.

I would argue that this information is just as important to the project as the insights you are getting from participants, so pay attention, question comments they make, probe deeper and jot down anything important for later use.

Once you understand the potential audience, you can prioritise effectively, placing the most engaging insights front-and-centre.

Its important to note, that this doesn’t always prioritise the way you think it will. Sometimes a positive validation is more important than a user issue. Sometimes the process of research (and working closely) reveals previously unknown priority that should now take centre-stage. But you will only know this from understanding your audience well.

#2. Lead with the “Now What”

Research in a commercial setting is likely to be part of a strategy or initiative to help service customers better and generate growth. It therefore must not only slot in neatly within the wider process and deliver better understanding, but lead clearly to a set of actions that can be taken in the next phase.

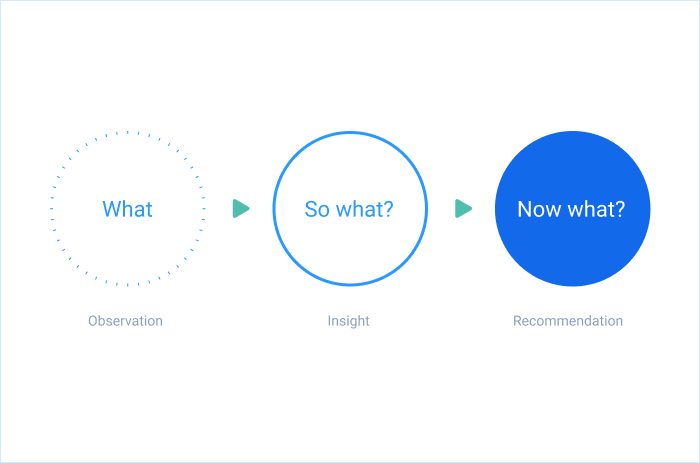

Taking cues from Terry Borton’s reflective model (1970), as adapted by Gary Rolfe et al (2001), there are 3 core elements of analysis and reflection:

1. What we saw // The observation // The “what”

2. What it means // The insight // The “so what”

3. What to do // The recommendation // The “now what”

I go into more detail on this below, but for now we should consider which of these will be quicker to take into the next phase.

Each element requires a cognitive leap to get to the next.

So while your observations and data (1. What) may be interesting and lead to greater knowledge, it takes some extra interpretation to understand truly what it means (2. So What), or what we now believe to be true about customer mindsets, behaviours or usefulness of UI elements.

But similarly, greater insight (2. So What) needs a further cognitive leap to get to the recommendation (3. Now What), the answer to how the product, service, strategy needs to evolve to be more effective.

So if you lead your report with either of the first two, you are in effect delivering a higher cognitive burden to the next phase.

Lead with “Now What”, and your readers will understand clearly what to expect in the next weeks and months.

Also, those who only have time to scan your report (often the more senior sponsors) will be given the clearest signal possible as to the potential impact and ROI of the resources put into the research, leading to greater engagement and belief in the power of research to drive efficient decision-making.

#3. Clear, consistent, attractive page architecture

As UXers, we have the tools and skills to tell stories and build understanding through consistent, usable visual architectures.

These skills should be put to use in defining your report. Most reports I’ve seen tend to follow a good structure — Exec Summary > Top-level Themes > Details, and this is good. But many fall short on consistent architecture for their insights, specifically when it comes to how the report is written, page-by-page.

If you think of your report as a web-page, you can begin to standardise the output using a set of key elements for every point you want to make. The following are not new, or groundbreaking, but important to keep consistent and present:

- The Quote

This should be the last thing you add, once you know the story you are trying to tell. Keep it short and snappy. Most will be scanning your report, so a long paragraph quote will not draw the eye. - The Observation (What we saw :: Past tense)

This is your evidence, so put it in the past tense as a statement about what you saw. Again, long paragraphs are unappealing, so keep your statements short (max 2–3 lines) and pack your words with meaning. For example:

‘Participants in this study found it difficult to…’ is too long. Try saying ‘A few struggled to…’ instead. This is a shorter statement and also conveys quantity. - The Insight (What it means :: Present tense)

This single statement should summarise a group of 3 to 6 observations and quotes. It should be written in the present tense and describe something you now believe to be true, based on the evidence. It is also important to use each insight to answer key objectives or assumptions made up front. I normally end up with between 15 and 30 insights in total (for a 1–2 day UX-lab session), with ideally 1 page per insight. - The Recommendation (What to do)

Lead with this. It should be a direct response to the insight and take the form of a specific command or action (more on this in the section below). If you have more than one for a key insight, then lead with the most important and place the others elsewhere on the page. - The Visual

Each insight should be accompanied by a visual, either a chart (if you have enough numbers), screenshot, design or photograph to add context, additional insight or convey the key recommendation.

Each page should ideally contain all of the above, in a consistent and scanning-conscious layout. For PowerPoint slides, this is the template I use:

Finally, it is also worth considering if a PowerPoint deck is truly the best way to convey your stories. Perhaps a poster, website or InVision board would have more impact. But in all cases, the key elements must be there, and must have clear, consistent visual hierarchy. Once you know your hierarchy, writing your analysis will be easier.

#4. Be specific and bold

One of the reasons the Uber UX team struggled, according to Elsa Ho’s account, was because too often, they acted as a neutral observer, focusing more on unbiased suggestions than strong opinions on the way forward. I have seen this throughout my career too, and it makes it more time-consuming for the reader to interpret, brainstorm and prioritise next steps.

As analysts and designers, we need to be more confident with our recommendations. We should believe that we, as objective observers, do have important opinions to be taken seriously.

If you have invested time in understanding your audience (see above), then you will no doubt be in a strong position to make specific recommendations.

Even better, if you spend time with your stakeholders during the research, ask them to jot solutions down on post-its as they crop up. You can use these in your report for even more validity.

The worst that can happen is that the recommendation is rejected, in preference for a better idea, of higher priority action. But either way, these decisions can be made quicker with a set of specific actions instead of more questions.

Here are some examples of do’s and don’ts:

—

Don’t say this:

“Consider revising the homepage to meet X objective.”Do say this:

“Place X above Y on the homepage hierarchy, as it is higher priority for Z user group.”

‘Consider’ is not a strong enough statement, as it requires extra effort to understand and interpret what needs to be done. Many teams will not have time to do this for every recommendation.

A specific instruction, with concise reasoning, is better. This allows the design team to immediately try out ways to resolve through page architecture.

—

Don’t say this:

“Explore options for button naming”Do say this:

“Change button wording to X, to help convey Y”

‘Exploring’ also needs extra effort, potentially a brainstorming session to understand and generate ideas. A well resourced product team may have time to run a brainstorm for button naming, but many wont.

A specific recommendation offers the chance for some to focus efforts elsewhere on higher priority challenges. Concise reasoning also allows people to challenge it if they feel strongly enough.

—

Don’t say this:

“Change the heading to make X clearer”Do say this:

“Front-load the heading with X so scanners spot it more easily”

‘Make clearer’ leaves the solution open to discussion and a risk of a sub-optimal response.

As UXers, we should be as aware as any of the primary usability recommendations for most contexts, so stick your neck out and state what you consider to be the best solution.

#5. Add Ratings and Priorities

Finally, it’s important to convey a sense of urgency and priority to your reports. This is the final step to help those in the next phase decide what to tackle first. There are many ways for teams to prioritise actions — the Impact / Effort matrix is a good one. However, it may be too far beyond your research remit to explore effort, so a good end-point for your report would be to indicate user impact.

A standard approach is to use a traffic-light system, one for each ‘Insight’:

- Green: A Positive rating reflects strong characteristics that appear to be working well and should be maintained in future phases.

- Amber: An Caution rating, these have a detrimental affect on the experience and should be considered as soon as is practical.

- Red: A Negative rating reflects aspects that will seriously harm the experience, and should be addressed at the earliest opportunity.

However, over the years we have seen the need to develop this further. The above scale actually has two scales baked into it:

1. Positivity

2. Priority

It is possible to have a negative but low priority insight, or a positive and high-priority insight. So these two scales should be separated out for each insight and recommendation. This is how we do it, using a simple block visual aligned with each insight:

By doing this, you are helping the scanners hone in on the important topics, but also offering an easy way to set a prioritisation list for next steps.

So there you have it. These techniques have been developed over 5 years at some of the largest organisations in the world. They are by no means an exhaustive list, but have certainly helped me and my teams deliver reports that don’t gather dust and have the impact they deserve.

If you have anything to add, have a question, or would like to challenge anything please comment below. I’d love to hear from you..

Opinions expressed are solely my own and do not express the views or opinions of my current and past employers.