What makes intuitive products intuitive?

Who wouldn’t want an intuitive product?

Something that is simple to grasp, and easy to use. Something you can pick up with no prior knowledge and be able to utilise to help do whatever you’re trying to get done. Surely everyone wants that! So why on earth are there so few intuitive products?

The answer I’ve come to is this:

I don’t think it’s clear how to design for intuitiveness.

How do you create intuitiveness? Do you just have to remove features? Can only simple products achieve it? Is it just all about a good onboarding? How about a clean UI? And (after creating some monstrosity), is intuitiveness just overrated — users will learn eventually, right?

First let me say, intuitiveness is worth it. In a world of seemingly infinite product choices, the first minute of trial usage is probably the most important for the product’s success. If someone understands how they can solve their immediate problem with it, they’ll continue using it until they have a reason not to.

One thought on intuitiveness is that it equates to minimalism (largely by removing any non-essential features). This might work, but it’s kind of cheating — of course you can stumble upon intuitiveness if there’s only one thing it can do. Too bad it’s also then useless for solving anything but the most simple problems.

Fabricio Teixeira does go further, breaking intuitiveness down into a foundational set of design principles in his practical article What “intuitive” really means. But somehow I still felt like I was missing the underlying why?.

Instead, to answer the question of what makes intuitive products intuitive, you can look to how our brains actually process new things.

What happens in our brains when we come across something new?

If you’ve already read my previous article Clean Code Is All In The Mind, you can skip ahead as I’m just copy-pasting this section.

Let’s say you come across a book on a table written by an author you’ve never heard of before. Do you know how to use the book? Of course you do! If the cover looks interesting you’ll pick it up, and you know if you turn it over to the back side (that you have never seen in your life), there will likely be a blurb for you to read. You know that you can open it and there will be paper pages inside. You know you should start from the first outermost page, and read through it, page by page.

So how do you know so much about how to interact with something that you’ve never even seen before? The answer is Mental Models.

Our brains are exceptionally good at pattern matching, and so when we come across a book, our brains can access an existing mental model based on all the previous experiences we’ve had with books in the past. And it’s this mental model that provides us with a theory on how to interact with the very book in front of us.

It’s this ability for humans to store, pattern match, and retrieving complex mental models better than any other animal, which gives us our relative super intelligence.

Ok, but what is a Mental Model?

We can’t store every detail about every single thing we come across in the world as discrete memories inside our little heads. Plus it wouldn’t help much if every time we came across something slightly new and different (for example a new book) we didn’t know how to interact with it.

Instead, we use mental models. (In the brain these are just a connected set of neurons, and in machine learning these are like a layer of nodes in a neural network — but this isn’t really important). Think of a mental model like a block of knowledge. A theory representing how something in the world works. A small piece of logic.

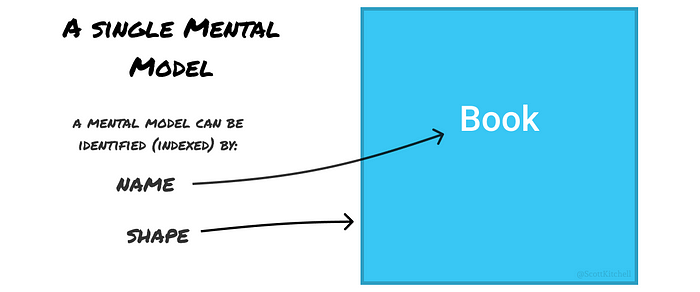

Here we can identify the mental model by its shape, but in reality, we can identify our mental models not just by how it looks, but by a sound, smell, or any other combination of senses that make it distinctive. When we see a book, or hear the word “book”, our minds immediately go to the index for the mental model we have for books.

On closer inspection, a mental model also contains the related knowledge on each part making it up — mental models within mental models!

If it helps, you can also think of them like folders in your computer, or like Lego bricks stacked into small models.

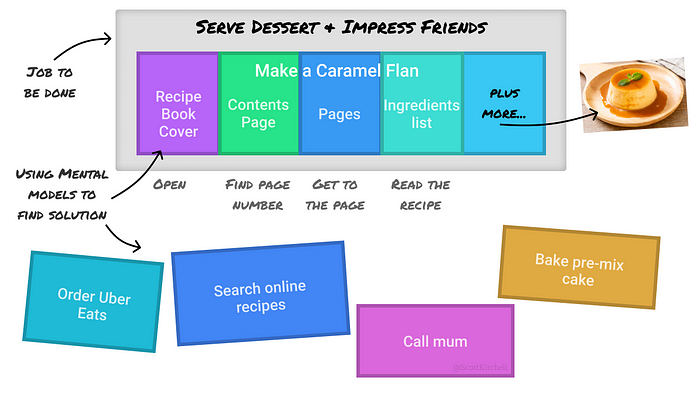

However, the power of mental models isn’t in how they store our knowledge, but rather how they help us to solve problems. When we have a job to be done, it’s as if we have a hole in our understanding of how to move forward. The job needs to be filled with the knowledge of how we can get it done.

To fill this hole, we can experiment through stacking mental models together in our mind like Lego bricks, until we get something that fills it in an effective way.

Keep in mind, people’s ability to experiment with their mental models varies person to person. If you’re a creative problem solver, this may be easy, but many people may need solutions to be more obvious.

A side note here is the role of marketing. If potential users don’t have a mental model representing your product, then how can they experiment with it in their mind to work out how it could help them solve their problems. Their existing ideas (mental models) on how to complete a job have to be pretty bad for them to realise that maybe they don’t yet know the best solution and to commit to doing more work searching for a better one.

Marketing promoting an accurate mental model for your product can give people an alternative solution to experiment with, and could save them time and effort in finding you or your competitors. Creative, entertaining, and high quality marketing material likely have little to do with it though.

Back to intuitiveness

The thing to remember about mental models is that they’re just your theories on how things work, and they’re often wrong.

Magic, jokes, and optical illusions often play on this in a lighthearted way to trick your brain into initially using the wrong mental model, so that the punchline can surprise you. This can be fun, but since we need to use mental models to solve problems, using the wrong mental models can also breed confusion, and a lack of confidence in using a product.

Because of this, products that either promote an inaccurate mental model, or require a complex set of mental models to fully comprehend will be unintuitive to use.

Intuitiveness can be created by designing every part of a product in reference to a mental model, and then promoting the mental model through the UI and marketing.

In other words, keep the complexity of the mental models required to a minimum, and add affordances in the UI and you’ll have an intuitive product.

For example, if you think of the pre-iPhone smartphones (like the HTC shown above), they required a multitude of mental models to understand. There were various menus, sliding tabs that all had different “fancy” UI, and worst of all, the same functionality was often duplicated in different places with different UI (Windows Mobile contacts, or HTC TouchFLO 3D contacts tab).

I loved the HTC as it was something to explore, but most people don’t like to explore their tech, they just want it to help them.

The iPhone changed this. It didn’t require you to have a mental model for each menu, each UI, and for various similar programs.

It’s was simply a menu of apps — each with their own functionality contained within it. Want to do something, anything at all? It’s always the same. Look for the app that does it, and open that. Even the settings was just an app. Because of this anyone, not just the tech-savvy, could understand how the device could be used to help solve their problems.

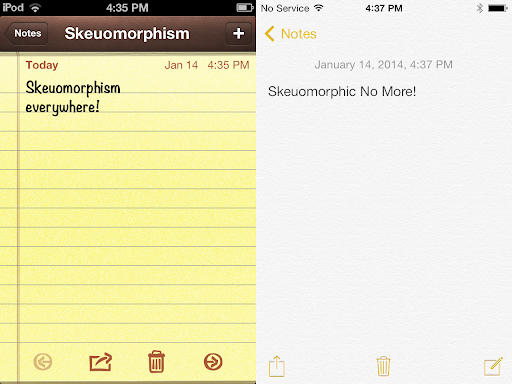

All the apps had a similar UI too, and (if you remember skeuomorphic design) they often even looked like how they do in the real world. This helped users retrieve their existing mental models so they could predict how to use the new device.

Another side note. Interesting to see the use of widgets on the iPhone home screen now. Android have had them for a long time with mild success. Just apps no more.

But existing users find it intuitive…

Once you know the mental model for a particular product or feature, no matter how unintuitive it was at first, you’ll believe it’s logical. This can be a problem if you’re familiar with your product.

For example most idioms like “happily ever after” don’t have an intuitive meaning anymore, and so you likely have a mental model just for this phrase (does sadly ever before make much sense?). Those learning english might say it’s unintuitive.

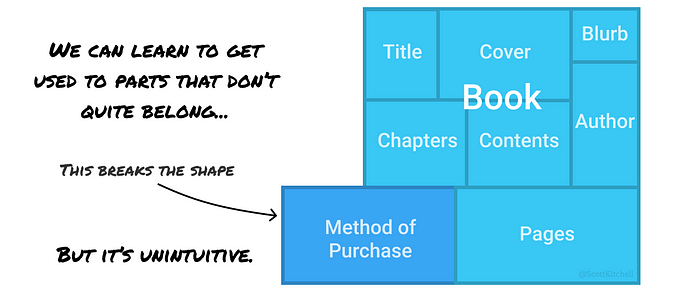

Mental models are literally the logic within our heads, so if it’s in there, you’ll see the logic in it. From the outside however, others will not. Unintuitive mental models are like irregular looking blocks — They don’t fit well with other mental models which makes them harder to remember, and problem-solve with.

If you can recognise the mental models your users require to understand your product, you’re on the right track. If you find that they’re complex, or they’re not consistent with the mental models your UI and marketing promote, you have an opportunity to increase the intuitiveness. Another easy way to know — just ask your new users what they think.

Recognising the complexity of the mental models people require to understand a product is the path to understanding intuitiveness.

Intuitiveness can be created by designing every part of a product in reference to a mental model, and then promoting the mental model throughout the UI and marketing.