The art of user interviews

How to unlock hidden user needs by collecting stories

We’ve all heard the adage often attributed to Henry Ford; “if I asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

So why bother conducting user interviews then? No?

Well, uncovering users’ needs is more than simply asking their opinion.

Sure, that adage is right. If you did ask people back then, a lot of people probably would have replied:

- A faster horse

- A more comfortable horse to ride

- A horse that obeys my orders

- …perhaps one that doesn’t kick me…

You get my point.

However, a lot of their answers would be anchored by cognitive bias.

Wikipedia defines cognitive bias as “the systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment, whereby inferences about other people and situations may be drawn in an illogical fashion. Individuals create their own “subjective social reality” from their perception of the input.”

In this case, likely a mix of availability bias: “I rode my horse this morning, and it was uncomfortable” and anchoring basis: “The way we travel today is by horse…therefore I can only think of ways to improve travelling by horse.” …among many others.

And that’s the kicker.

We are all biased in some shape or form. It’s part of being human.

The art of user interviewing, however, is navigating these biases.

Let’s go back to some of those possible responses:

- A faster horse = I want to get to my destination quickly

- A more comfortable horse to ride = I want to travel in comfort

- A horse that obeys my orders = I want to be in control

- …perhaps one that doesn’t kick me… = I don’t want travelling to be a chore/painful

One of discovery and user research's first tenants is stripping solutions away.

In all these possible responses, there is a deeper underlying problem that their proposed solution (i.e. “faster horses”) is trying to solve.

Your job as the interviewer is to uncover these problems and needs, not to gather solution ideas from them (although you can do this too — but only when you want/need to and after you’ve explored the problem space first).

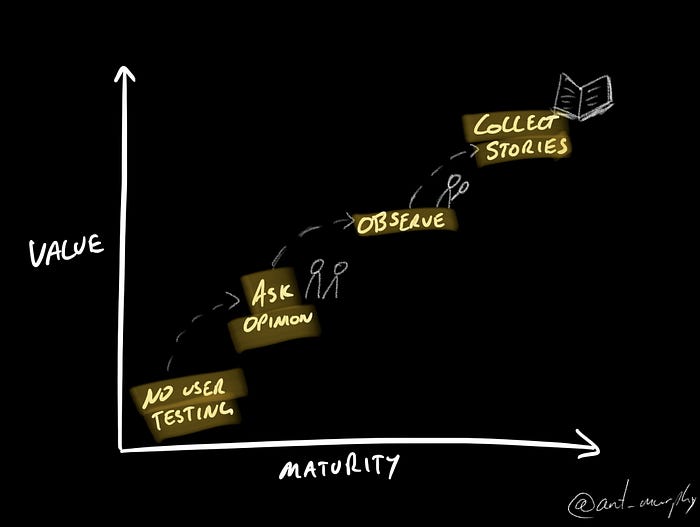

A maturity progression to User Interviews

I’ve observed a common maturity progression when it comes to conducting user interviews.

- We often begin by asking for user’s opinions

- We then progress to observing user’s

- And finally, we mature to collecting stories

1) Asking for the user’s opinion

I made this mistake, and many others have too. When we conduct user interviews for the first time, we often start by asking for our user's opinions on things.

- Do you like this?

- What suggestions for improvement do you have?

- Is this a challenge in your day-to-day work?

- etc

The problem here is that we’re asking them “if they want faster horses?” and we know how that can turn out.

The other problem here is that it doesn’t give me an insight into their actual behaviour.

Liking something doesn’t equate to using it or buying it — both of which are behavioural.

Liking something ≠ buying it…nor does it mean they will use it either.

I see many things I like, but that doesn’t mean I need them nor end up purchasing them.

The second problem with opinions are they are just that — opinions!

Opinions aren’t facts — would you bet your company on someone’s opinion? I bet not.

More advanced product people will begin to recognise these flaws and ask more pointed questions:

- Do you think you will use this?

- Can you see how you might use this in your day-to-day?

Although an improvement, they are still based on opinion rather than fact.

This brings me to ‘observing’.

2) Observing users

Observing is much better than asking. For two core reasons:

- It’s factual, not an opinion

- It helps to reduce biases

Depending on your questions, they can be leading and invoke an anchoring bias and/or other biases.

“The two interview protagonists (Designer and User) have their own cognitive biases that influence the results, can bring about false conclusions and lead us down false paths.” — Abdou Ghariani

Anchoring is a finicky one because that’s not their bias coming through but yours.

This is an important factor to be mindful of when interviewing, and you should always practice ensuring you remain as neutral as possible and not interject your bias.

The framing effect is another bias that is prevalent here. It describes a phenomenon where people react differently to the same information depending on how it is worded.

Observing can help. By having fewer questions and spending more time quietly observing your users, you can learn a great deal whilst avoiding chances to invoke bias.

A great example of the power of observing is through user testing. Observing a user attempting to use your prototype is much more powerful than guiding them through it.

Having done this many times before, you quickly uncover aspects that are either misinterpreted or don’t make sense which works well for uncovering user’s mental models:

- What assumptions are they making?

- Do they think something is clickable or not?

- How do they assume the prototype is supposed to be used? etc.

Observing rather than asking for opinions gets you much closer to understanding your user's needs.

I experienced this a few years back when I was working on a new product for truck drivers. When exploring the problem space, we went out and spent a day with several truck drivers to observe how they overcame the challenge of finding a fuel station that their vehicle would fit in.

We observed that they frequently used their radios to talk with other truck drivers nearby. We observed that they had a heavy reliance on the truck network and other truck drivers for advice. More interesting was that it was extremely effective. In the end, although there was a clear problem, we found that it was not common enough. Truck drivers frequently drove the same route, and if they ever were lost, they would radio nearby truck drivers for a solution. This was something that they were used to doing, it was an existing habit and was effective.

If we had brought truck drivers in or simply asked their opinions, I’m not so sure we would have uncovered something like how ingrained using the radio was for them nor how effective they are.

Going to your users and observing them in their context is a common user research technique called ‘contextual inquiry’.

“Contextual inquiry is a type of ethnographic field study that involves in-depth observation and interviews of a small sample of users to gain a robust understanding of work practices and behaviors.” — Nielson Norman Group

Observing users in their context is great for uncovering contextual nuances that might have been missed. As they say, don’t bring users to you. Go to them.

Don’t bring users to you. Go to them.

3) Collecting Stories

The final evolution is collecting stories.

Starting out with asking our users their opinions, we then move to observing them (ideally in their context) but to unlock the full power of user interviews we advance to collecting stories.

Collecting stories is easier than it sounds. It just takes a bit of practice. The hard part of collecting stories is synthesising them into actionable insights.

My hypothesis is that one of the reasons why we often begin by asking opinions is because the relationship between the question and the responses (data) is 1:1.

i.e. X number of users said they didn’t like it, so it’s a bad idea. However, behavioural science will tell us that things are seldom that straightforward.

Therefore whilst opinions are subjective and observing users comes with many upsides, performing them in a controlled environment can miss out on taking their context into account.

Teresa Torres describes what she calls the ladder of evidence.

The ladder of evidence details the progression:

- Asking what they would do

- Asking what they have done in the past

- Asking for specific stories on what they have done in the past

- Ask them to show you what they did (or simulate a new experience)

- Observe them during a real-life instance (or live test a new experience)

As you go up, both time and effect increase however, the value of what you learn increases too.

As you can see, the ladder progresses from asking for opinions to probing for past behaviours up to contextual inquiry.

Collecting stories are about observing or detailing past behaviours.

Just like Torres’ ladder of evidence, rather than asking, “when was the last time they used it or did something similar?” get them to talk about that experience. Facilitate having them walk you through what they did, why, and how.

What you’re trying to achieve is to build a picture of past behaviour. There’s nothing more concrete than actual behaviour.

Past behaviours represent what they actually did, not what they think they would do.

Past behaviour is fact. Everything else is either an opinion.

Unfortunately, the challenge, as mentioned earlier lies in synthesizing these stories. Stories on their own aren’t useful.

The relationship between the action and insight is not always immediately clear. Stories require translation and synthesis to convert a story into actionable insight.

Wrap Up

This by no means is designed to be a maturity model or to downplay the role of certain forms of observation or asking users their opinions.

I wouldn’t fret if you find yourself asking users their opinions, especially not at the beginning of your product career. I started there too, and still occasionally ask the odd, opinion-related question.

Perhaps a good way to frame this is as a guide.

A guide to knowing the blindspots and finding ways to increase the effectiveness of your user interviews.

What I hope this does, however, is challenge you to reflect on the way you are currently conducting user interviews and to be mindful of some of the inherent challenges that, say asking opinions might bring.

Finally, if you’re not currently seeking to collect stories or have never done so, I hope this inspires you to try it. To try a different style of interviewing and see the results.